Africa is sitting on the raw materials to power the world’s green revolution — cobalt, lithium, graphite, rare earths.

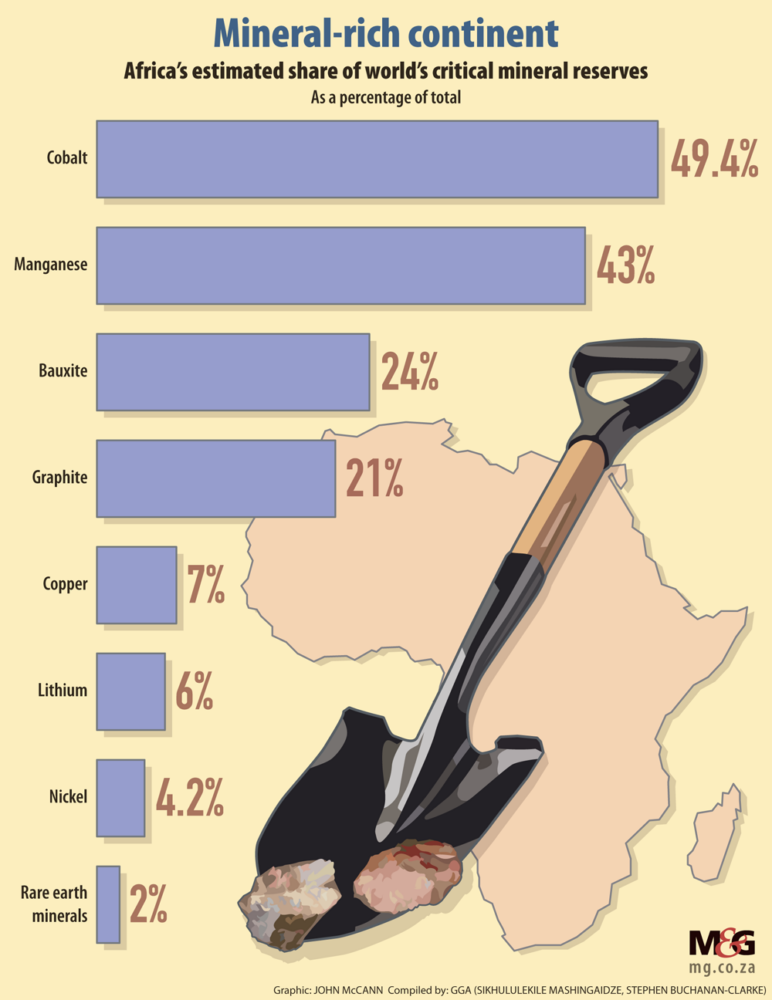

Africa, which holds significant estimated shares of the world’s total reserves of bauxite (24%), cobalt (49.4%), copper (7%), graphite (21%), lithium (6%), manganese (43%), nickel (4.2%) and rare earth minerals (2%), is at the centre of a global race for critical minerals required in the clean energy transition.

Exploitation of these resources should help to boost trade, industrialisation and development, but Africa’s track record is littered with examples to the contrary. Resource booms become drivers of corruption, conflict and ecological destruction and weaken governance institutions.

Given the continent’s economic problems, rapidly expanding population and mounting environmental pressures, there is a closing window of opportunity to ensure this new wave of mineral extraction breaks from historical patterns to become a catalyst for inclusive economic growth and long-term sustainability.

Zimbabwe’s lithium sector exemplifies both the opportunities and dangers inherent in the global race for critical minerals — a subject explored at a May 2025 conference hosted by the Centre for Natural Resource Governance (CNRG) titled Ensuring Equitable Distribution of Costs and Benefits in Critical Minerals Development.

Lithium, used in consumer electronics (including batteries), electric vehicles and renewable energy systems, has become an essential mineral to many of the modern industries driving economic prosperity and the global transition to clean energy. As drone warfare continues to revolutionise modern warfare, access to lithium-ion and lithium-polymer batteries has also become an important national defence issue from Washington to Beijing.

Zimbabwe is endowed with substantial lithium reserves. Since 2021, the sector has attracted more than $1.2 billion in foreign direct investment, with exports surging 800%, from $7 million in 2021 to $600 million by 2024. Investment in the sector has been dominated by Chinese companies including Rwizi Rukuru, Shengxiang Investments, Sinomine Resource Group, Chengxin Lithium, Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt and Yahua Group. This investment in the sector has been highlighted by Mines and Mining Development Minister Winston Chitando as crucial to the government’s wider national development strategy.

But, as shown in previous research by Good Governance Africa and the CNRG, Zimbabwe’s mining sector often fails to translate into broad-based economic prosperity. Several mining operations have also been associated with incidents of human rights abuses, corruption and environmental degradation, with local residents disproportionately suffering the adverse consequences.

The surging demand for Zimbabwe’s critical minerals presents a defining choice for both government and mining investors: they can either leverage this opportunity to empower local people and foster inclusive development or fall back into familiar patterns of exploitation. During conference proceedings, several measures were highlighted as necessary to maximise Zimbabwe’s chances of seeing the former option.

First, Zimbabwe’s mining sector requires comprehensive legal and governance reforms to unlock its potential for inclusive development. The current system, which vests mineral rights in the president and is administered through the mines and mining development ministry, creates opacity and excludes key stakeholders from decision-making processes. Transferring these rights to an independent regulatory body subject to parliamentary oversight and accountability would enhance transparency and ensure broader participation in mining agreements.

Simultaneously, fast-tracking the implementation of a comprehensive mining cadastre system is essential for providing real-time, accurate records of mining claims and licenses. This technological infrastructure would serve as a foundation for reducing corruption, limiting discretionary decision-making and aligning Zimbabwe’s mining sector with international standards.

Second, prioritising beneficiation to stimulate industrial development and local job creation is essential. In this respect, Zimbabwe passed the Base Minerals Export Control (2022), which includes a ban on raw lithium exports by 2026 to encourage investment in local processing facilities.

On 10 June 2025, the minister also announced a ban on the export of lithium concentrates by January 2027. Although these measures were designed to maximise benefit through localised processing of lithium, a CNRG press statement in response to the minister’s pronouncement noted with concern that “this urgent reform is being delayed into irrelevance”.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

This, as CNRG further highlighted, “should be with immediate effect to prevent further natural capital depletion from unchecked lithium exploitation, which has devastating socio-economic and environmental implications. Zimbabwe’s lithium wealth risks being squandered, as unchecked exports, weak regulation and opaque deals undermine its potential for industrial transformation”. Local minerals beneficiation does not always make economic sense. But, where the opportunity for value addition is clear, it must be taken and supported through coherent industrialisation policies.

Further to this, China monopolising the sector could undermine these efforts, with Chinese companies already leveraging their position to undermine local beneficiation initiatives. Diversifying investment in the sector by addressing governance issues (currently deterring many Western investors) and leveraging opportunities such as the European Union’s Critical Raw Materials Act and the US Minerals Security Partnership (aimed at securing critical mineral supply chains) would help to strengthen Zimbabwe’s negotiating position.

A good step in this direction was the first European Union-Zimbabwe Business Forum held from 20 to 22 May, focused on renewable energy and mining investments, among other aspects.

Beyond diversifying investment partnerships, realising the intentions of the Base Minerals Export Control will also require concerted investment in the infrastructure required for local beneficiation projects to operate effectively, a consistent regulatory environment, and decisive action against corruption.

Third, strategic resource management should balance national sovereignty with economic pragmatism to maximise benefits from Zimbabwe’s mineral wealth. Moving away from disadvantageous long-term trade agreements while avoiding excessive nationalisation will help Zimbabwe capture fair value during price fluctuations without deterring necessary investment. Central to this approach is the need for long-term planning that addresses resource depletion through economic diversification strategies and sovereign wealth mechanisms, on condition that these be well governed.

Fourth, community empowerment and rights protection regarding land and water should be prioritised to ensure that local populations benefit from, and participate in, decisions affecting their areas. There is a need for ongoing, comprehensive government and civil society-driven capacity building programmes to educate people about critical minerals, associated opportunities and potential risks, enabling informed participation in mining-related decisions. Community involvement is a principle provided for by the Constitution on national development, and in the Environmental Management Actt. But the implementation of these provisions remains a problem.

In this respect, international best practice frameworks such as the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights provide useful guidelines on how mining companies, civil society and government can play a role in advancing these goals. But creating the conditions under which these can be effectively implemented will require the Zimbabwean government to address long-run governance and human rights issues, as well as creating an enabling environment for civil society to operate.

Finally, environmental sustainability and social responsibility must guide Zimbabwe’s approach to critical mineral extraction, ensuring that the pursuit of economic benefits does not compromise long-term environmental and social well-being, particularly for the mining communities. Mining operations should be required to adopt cleaner technologies and implement robust mitigation measures, including cleaner coal technologies, where fossil fuels remain necessary for processing.

Humanising the broader energy transition can be achieved through gradual, community-sensitive steps rather than disruptive changes that harm rural livelihoods.

Upgrading Zimbabwe’s obsolete energy infrastructure is essential for supporting both mining operations and broader economic development while improving national energy security. By embedding environmental and social considerations into mining policies from the outset, Zimbabwe can position itself as a responsible supplier of critical minerals while building a sustainable foundation for long-term development that benefits all citizens rather than perpetuating historical patterns of exploitation and exclusion.

Sikhululekile Mashingaidze is the lead researcher in Good Governance Africa’s Peace and Security Programme and Stephen Buchanan-Clarke is the head of the programme.