With or against us: AI can enhance the efficacy of various clean energy sources such as solar, wind, geothermal, biofuels and hydroelectric power.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems need to be powered.

They require compute resources, comprising hardware and infrastructure components – primarily Central Processing Units (CPUs), Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), Tensor Processing Units (TPUs), Neural Processing Units (NPUs), memory, storage and networking – that provide the processing power, data handling and parallel-computation capabilities required to train, run and scale AI models and other intensive workloads.

These compute resources require energy-hungry data centres and AI factories.

A data centre is a physical facility that houses IT infrastructure, such as servers and storage, to manage, process and store data. An AI Factory (which leverages data centres) is designed to develop, train and deploy AI models at scale, focusing on computational resources and AI workflows.

The power requirements of data centres and AI factories are at the gigawatt level. For example, a typical AI factory’s energy requirement is 2 GW (2000 MW), equivalent to that of a city like San Francisco or a country like Zimbabwe.

Furthermore, there is a demand for large volumes of fresh water for cooling (to prevent hardware overheating), putting pressure on the available water supply for human consumption, agriculture and other industrial purposes.

Hence, the large carbon footprint of AI systems primarily stems from the significant compute resources required for energy-intensive tasks such as training and deploying Large Language Models (LLMs).

These tasks require high-performance hardware, such as GPUs and TPUs, which consume substantial electricity. For example, training a single LLM can emit hundreds of tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, comparable to the emissions of several cars over their lifetime. Furthermore, as explained earlier, these models are trained and run in energy-hungry data centres, which must also be cooled.

Larger AI models require exponentially more energy. A model with billions of parameters demands far more computational power than a smaller one, resulting in a significantly larger carbon footprint. Once trained, AI models continue to consume energy during deployment, particularly for real-time or large-scale applications.

Common examples include AI in content recommendation systems, search engines and real-time translation, which require continuous processing power. The iterative nature of AI research, where models are trained and retrained to optimise performance, means that significant energy is expended in the development phase before a final model is deployed.

Hence, a country’s participation in driving the AI revolution (through data centres and AI factories) carries high environmental costs.

According to the International Energy Agency, total global electricity consumption by data centres could reach the level of Japan’s energy intake by 2026.

Another projection is that, in 2030, if all data centres worldwide were considered as one country, their overall energy demand would rank only fourth, behind China, the United States and India.

AI companies in highly industrialised economies are even exploring the establishment of private nuclear power plants to meet their energy requirements.

Some countries are ramping up their fossil-fuel-driven power supplies to meet AI energy demands – a direct reversal of clean energy transition commitments.

US President Donald Trump revealed on 23 January 2025, while addressing the World Economic Forum, that the United States would have to double its annual electricity production to lead and drive the AI revolution.

That is the extent of the enormous energy demand exerted by the technology. President Trump intends to use the Executive Order (which he signed on 20 January 2025) declaring a national energy emergency to address this challenge.

The legal instrument directs US agencies to utilise their statutory emergency powers to speed up the development and authorisation of energy projects.

Unfortunately, with his slogan – “drill, baby, drill” – Trump’s AI energy plan will be anchored by boosting fossil fuel production to the detriment of global climate policies and regulations.

While many data centres are increasingly powered by renewable energy, non-renewable sources such as coal, natural gas, derived gas, crude oil and petroleum products are still often used, contributing to emissions.

Clearly, AI poses challenges to the global supply of adequate energy, threatens freshwater supplies and has the potential to worsen the climate change crisis.

AI systems can be deployed to optimise energy generation, enhance grid management, increase renewable energy adoption, improve energy efficiency and expand energy access.

The technology can play a transformative role in making clean energy more accessible and sustainable.

Thus, AI systems can drive innovation in energy management, grid optimisation, renewable energy forecasting, smart energy consumption, global decarbonisation and the expansion of access to clean energy in underserved regions.

This transformative role of AI supports the achievement of UN SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), which seeks to ensure universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services, increase the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix, and improve energy efficiency.

Efficient energy generation and distribution are essential for achieving universal access to clean, reliable energy.

AI has the potential to enhance the performance of both traditional and renewable energy sources while reducing waste and improving reliability.

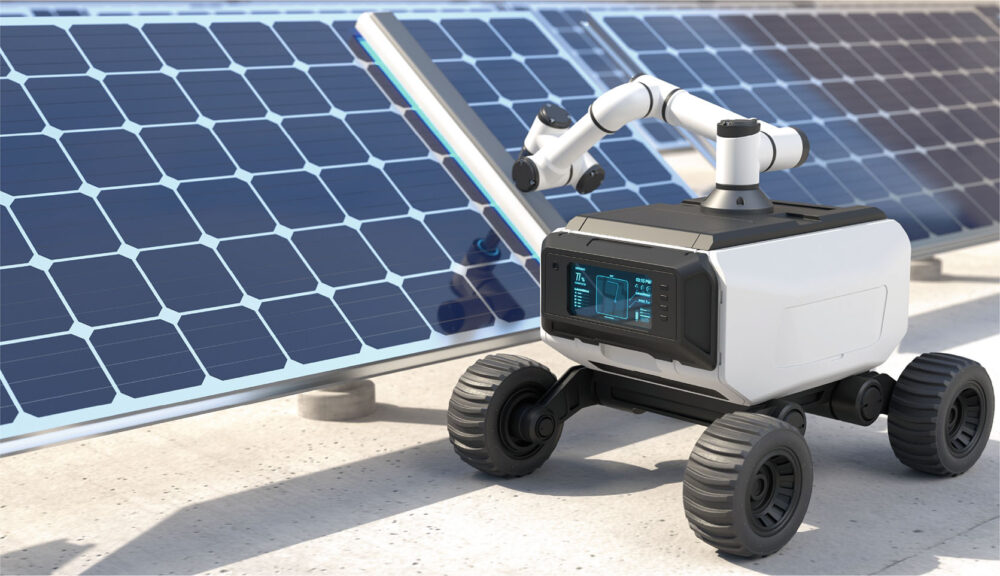

Indeed, AI can enhance the efficacy of various clean energy sources such as solar, wind, geothermal, biofuels and hydroelectric power. In traditional power plants, AI-driven predictive maintenance systems monitor equipment conditions in real time, identifying potential issues before they lead to failures.

By analysing data from sensor-embedded turbines, generators and other machinery, AI algorithms can detect signs of wear and tear, allowing operators to conduct maintenance proactively.

Renewable energy sources like solar and wind are essential for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but their intermittency presents challenges for a consistent energy supply.

Global electricity consumption by data centres could reach the level of

Japan’s energy intake by 2026.

Global electricity consumption by data centres could reach the level of

Japan’s energy intake by 2026.

AI-driven forecasting models have the potential to mitigate these challenges by accurately predicting energy generation from renewable sources, enabling operators to integrate them more effectively into the grid.

AI-based forecasting models use Machine Learning algorithms to analyse historical weather data, satellite imagery and sensor readings. These models can predict energy generation levels hours, days or even weeks in advance by identifying patterns in temperature, sunlight, wind speed and other factors.

This capability enables grid operators to plan for variability in renewable energy supply, ensuring a stable and reliable flow of electricity.

In solar energy, AI algorithms analyse satellite images and weather patterns to predict how much sunlight will reach solar panels.

By providing accurate solar irradiance forecasts, AI helps optimise solar power generation and supports grid stability.

In wind energy, AI can predict changes in wind speed and direction, enabling wind farms to maximise energy production during favourable conditions.

This improves the efficiency of wind energy systems, reduces reliance on fossil fuels and makes renewable energy a more viable option for meeting energy demands.

Energy efficiency is essential because reducing energy consumption minimises environmental impact and conserves resources.

AI offers significant opportunities to improve energy efficiency in buildings, industrial facilities and transportation systems by enabling real-time monitoring, predictive analytics and automated energy management.

In buildings, AI-powered energy management systems monitor and adjust heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems based on occupancy patterns, weather conditions and user preferences.

These AI systems help reduce electricity bills, lower greenhouse gas emissions and promote sustainable building practices by optimising energy use.

In industrial facilities, AI enhances energy efficiency by monitoring machinery performance, optimising production processes, and reducing resource use.

AI also optimises energy use in transport, particularly in electric vehicles (EVs) and public transport systems.

AI algorithms analyse traffic patterns, energy consumption and charging needs to determine optimal routes and charging schedules for EVs, reducing energy use and improving battery efficiency.

So, is AI a friend or foe?

(To be continued next week)

This is an adapted excerpt from the book “Deploying Artificial Intelligence to Achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals: Enablers, Drivers and Strategic Framework”

Professor Arthur G.O. Mutambara is director and professor of the IFK at the University of Johannesburg (UJ)