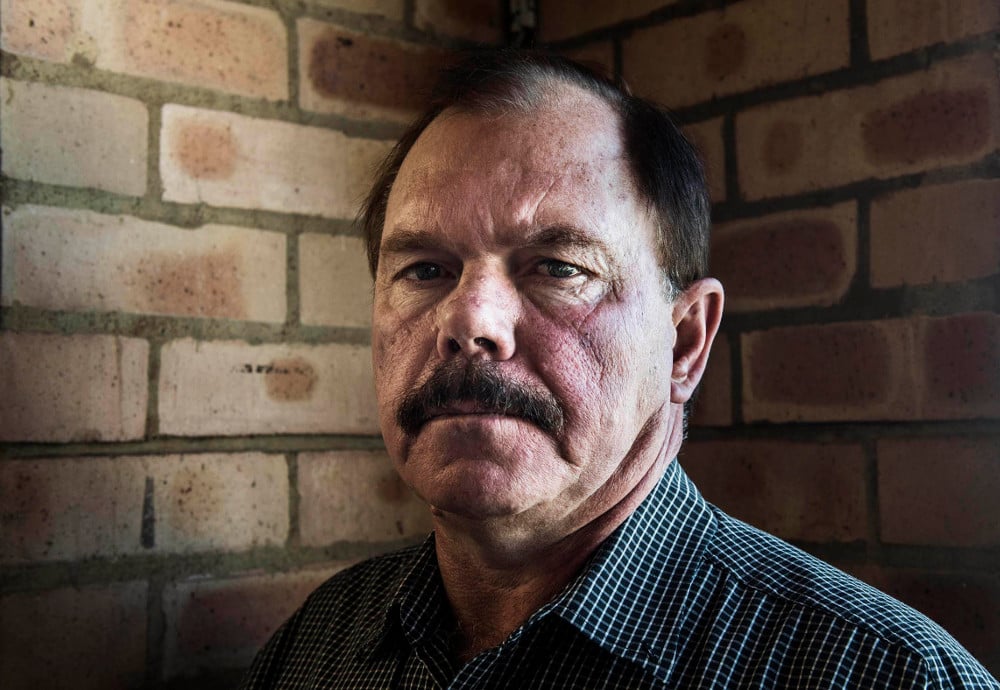

Douw Venter struggles to sit comfortably in the stiff, red, Wimpy booth in Heidelberg, a picturesque dorp 60km south of Johannesburg. One arm rests on the back of his bench while the other is on the table. But he has other, real struggles on his mind. Big mining is coming to the fertile farmland surrounding Heidelberg and it won’t take no for an answer.

“This is like standing in the way of a bulldozer,” Venter states. “There is no hope of stopping it.”

He has practised as a lawyer in the small farming town for a decade. Embraced by the Suikerbosrand River, Heidelberg has some of the country’s best farming land. Fields of maize and soya bean are fed by rivers running into the Vaal Dam – Gauteng’s main source of drinking water.

But the farmland sits above a large coal seam. Eskom’s 1 200MW Grootvlei coal power plant – built in 1969 – rises out of dull yellow maize fields 40km to the south en route to the eastern Free State. Anglo American Inyosi Coal has submitted a plan to the mineral department to build an underground coal mine to supply this station.

On April 16 it published a small notice in the local newspaper, asking if anyone had objections. “They almost slipped this through without anyone noticing. But luckily one farmer saw the advert,” says Venter.

His old Nokia rings as he talks, filling the small Wimpy with the canned sound of a heron. While taking on the mining giant, he still runs his practice.

One-month objection period

New legislation means people have only 30 days to object to the first phase of a mining application. “One month. It takes two months to do an objection to a small dam on a farm,” he says. “How can you object properly to a mine in one month?”

This mine will be the first large one opened since the national department of mineral resources took over environmental permits from their counterparts at environment affairs in January. Now mines only have to go through one department.

But the department has come under sustained criticism for not having people with the skills to adjudicate the environmental merits of mining applications.

Lawyer Douw Venter says trying to stop big mining is like standing in front of the bulldozers and it’s best to mitigate the damage. (Photos: Fredrik Lerneryd)

Venter repeats an often-used complaint: “Having DMR [department of mineral resources] as both the player and the referee is political gymnastics. It allows mines to push through applications with the least resistance.”

This means other concerns are ignored – such as water and food security. “Mines always lead to water pollution, and here we are supplying water to the Vaal Dam and Gauteng,” he says. Rand Water, which supplies most of Gauteng with water, has registered an objection to the mine.

Venter pauses and shifts again in his bench when asked whether it is impossible to stop the mining. He nods his head and acknowledges: “Ja. In my mind it is.”

Damage control

As a pragmatist, he is looking at damage control. The objections being raised by farmers should be aimed at ensuring the department of mineral resources places conditions on the mining, which is a fait accompli, he says. “We can then make sure that any noncompliance results in legal action.”

But that places 20 000ha of farmland at risk. Faan Botha, a towering farmer elected by locals to be their spokesperson, says this is some of the richest farmland in the country. His great-grandfather settled here a century ago, drawn by the soil and good water supply. Nodding towards a worn, white tray with water for his guests, he says: “That’s the first thing to go.”

Each hectare produces 10 tonnes of maize – compared with half that in other areas along the agricultural belt that runs along the southern border of Gauteng. The 60m-tall cement grain silos in the middle of this area hold 90 000 tonnes of food. Last year they processed 390 000 tonnes of grain. Most of this stays in South Africa.

Karan Beef – the largest feedlot in the country – sprawls over several farms a few kilometres down the rutted tar road. But the proposed coal mine will run underneath the silos, with an open-cast mine also slated next to the feedlot.

The mine’s scoping report says the environmental impact assessment has to be completed in 180 days. Farmers say this conveniently means it will be done in winter. “Of course they want it in winter. The water levels are down, there are fewer animals and less vegetation. It’s easier to write off the impacts as minimal,” says one. The farmers do not want to be identified for fear that it will jeopardise future negotiations with the mine.

Impact of coal mining

On one of the farmers’ tables is a stapled printout of a 2013 report on the Impact of Coal Mining on Agriculture prepared for the Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy, a collaborative research unit.

It states: “All underground mines will eventually collapse.” But the timescale for this is over a century, so is often not included in impact assessments. The soil is also sterilised, thanks to acidification and the collapse of soil fertility. But the worst effect is on water sources, it says. During operations, problems can be abated, but once mining stops operations inevitably flood and this leads to problems such as acid mine drainage.

“The effects of coal mining on agriculture are immense and some effects are irreversible,” says the report.

When farmer Faan Botha asked for more information than that in the scoping report he was told that ‘food security was not important; we need to keep the lights on’.

For Botha it is a catch-22. “We can’t keep the lights on and we are told electricity has to come at any cost. But we also need food security.” He has tried asking for more information than that contained in the scoping report and has not had any success.

The numbers listed as contacts on the report are not answered, he says. The one time he got through, Botha says he was told: “Food security is not that important. We need to keep the lights on.” His farmhouse, built by Italian prisoners of war, is adjacent to the proposed mining area.

‘Exploited for a long time’

Five high-voltage power lines heading towards the Grootvlei power plant tower over fields of fat sheep. Three underground gas pipelines also cross his land, heading to Sasol’s Secunda plant. “We have been exploited for a long time already,” he says in a jovial tone that never sounds downbeat. Taking a baseball cap from a rack of hats, he climbs into his single-cab bakkie and drives towards the proposed site of mining. Everyone Botha passes waves a greeting.

On the way he stops at a large farm, where the owner offers bottled water as he picks up the pile of toys left in the dining room by his grandchildren. The water comes from a Valpré plant upriver of the proposed mine.

He has a folder with all the different mining applications that have been made in the area. The high price of farms, driven up by the sale of land to mines in other provinces, means he cannot afford to sell and move elsewhere. Canada might be an option – global warming will see more arable land there, he says. “I am 60. In 20 years I won’t be around here sniffing coal ash.”

Most of the locally produced corn in the region is stored in cement silos outside Heidelberg.

The next stop is the proposed mining site, where the shaft and tailings dams will be located. It feels peaceful, almost like a graveyard. Huge blue gum trees block the wind. The only sound is the rustling of their leaves.

An abandoned missionary church stands nearby, with large cracks showing that it is close to collapsing. The Suikerbosrand River winds its way towards the Vaal Dam at the northernmost boundary of the planned mine. From here the only sign of its path is the thicket of trees that grow along the river.

“It’s a beautiful area,” says Botha. “But government does not care about food security so we will have the mining. And then it will all be gone.”

Moeketsi Mafokeng, spokesperson for the mine, says that all studies would be carried out in accordance with legislation. It will also follow its own “internationally benchmarked, rigorous guidelines and standards”. But any concerns the community has will be addressed during the consultation phases. “The company appreciates that the South Rand region is ecologically sensitive and culturally unique.”