Within the next five years, your flight to Durban could be powered, at least in part, by sugarcane-based ethanol or the carbon-rich waste gases from heavy-emitting industries in South Africa.

The country’s alternative fuels for the future of the aviation sector could, too, come from a locally grown modified tobacco plant called Solaris, or biomass from the clearing of water-guzzling invasive alien plants and garden waste.

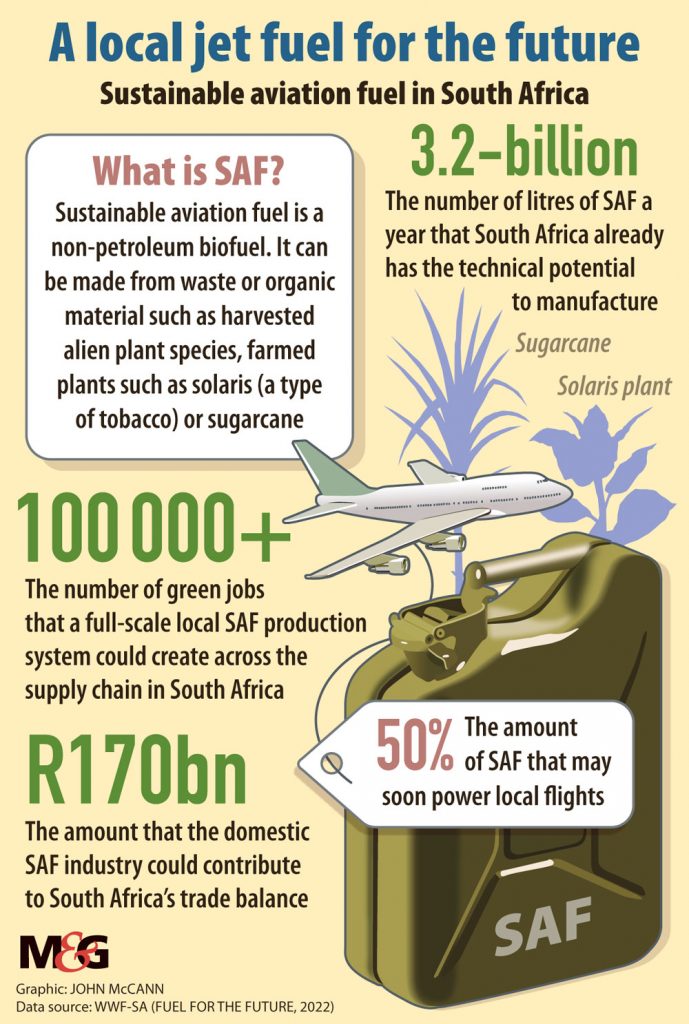

These are among the potential pathways for South Africa to lift off and become a major producer – and potential exporter – of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), decarbonising aviation to help limit dangerous climate change and pursuing key ecological and development objectives, according to a new report by the World Wildlife Fund-SA (WWF-SA).

The report, which is a blueprint for the production of SAF in the country, found that the large-scale SAF economy could potentially create about 100 000 green jobs along the supply chain, and improve the country’s trade balance by nearly R170 billion without affecting water, food or biodiversity.

“A domestic SAF industry could be a pillar of South Africa’s low-carbon economy, with the potential to provide decent new jobs and alternative employment opportunities for those affected by the energy transition.”

Decarbonising aviation

The commercial aviation industry accounts for 2% to 3% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. If no mitigation measures (efforts to reduce or prevent the emission of greenhouse gases) are taken, CO2 emissions from commercial aviation are expected to triple by 2050 because of a surge in both passenger and freight transport. By then, these emissions could account for over 22% of all human-caused CO2 emissions.

The aviation industry faces a challenge to decarbonise, the report’s co-author Farai Chireshe, a bioenergy analyst at WWF-SA, told Mail & Guardian. “It is often referred to as one of the ‘hard to abate’ sectors because direct electrification is not a solution particularly for long-haul transport. SAF plays a huge role in the decarbonisation strategy. It is estimated by the International Air Transport Association that 65% of emission reductions in 2050 will come from SAF.”

Farai Chireshe a Bioenergy Analyst, WWF South Africa

Farai Chireshe a Bioenergy Analyst, WWF South AfricaLow-hanging fruit

South Africa, the report reveals, has the immediate technical potential to produce 3.2 billion litres of alternative aviation fuels annually, “following the strictest sustainability requirements”. Introducing green hydrogen into the manufacturing process can extend this potential to 4.5 billion litres per year.

“This is enough to replace the use of conventional jet-fuel domestically up to a maximum blending threshold of 1.2 billion litres per year, while also providing 2 [billion] to 3.3 billion litres for export.”

If project development starts immediately, SAF produced in South Africa could come online in the next five years, Chireshe said. “Our research shows that SAF production from sugarcane-based ethanol and industrial off-gas are the low hanging fruits. South Africa has existing facilities such as Sasol Secunda and PetroSA (Mossel Bay), which could start producing these fuels in an even shorter timeframe.”

According to ASTM International – the regulatory board that sets specification standards for SAF – a maximum 50% of SAF can currently be used in commercial aircraft. “This means that in the next five years a flight to Durban could be powered by 50% SAF at most,” Chireshe pointed out. “However, the major aircraft manufacturers Boeing and Airbus, have said by 2030 it could be possible to use 100% SAF in commercial aircraft.”

The Sasol Ltd. Secunda coal-to-liquids plant in Mpumalanga, South Africa Photographer: Waldo Swiegers/Bloomberg via Getty Images

The Sasol Ltd. Secunda coal-to-liquids plant in Mpumalanga, South Africa Photographer: Waldo Swiegers/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Costly alternatives

For now, high costs remain the sector’s biggest challenge. This is mostly because the world has not yet started producing significant volumes of SAF and most of the production technology is yet to mature, Chireshe explained.

“As more sustainable aviation fuel production facilities come online, the risk linked to the technology nascency will reduce, lowering the cost of capital for projects and in turn the costs.”

Other capital support mechanisms such as grants and concessional finance can also help to reduce the cost of capital required for SAF projects, while SAF will also benefit from economies of scale as more production comes online.

Thousands of jobs can take off

The report describes how feedstock production could provide employment to 20 000 farm workers and possibly even bigger numbers of invasive alien plant harvesters. It would also preserve at-risk jobs in sugarcane production.

Tongat Hullet sugarcane plantations

Tongat Hullet sugarcane plantations

“The highest achievable localisation of all promising production pathways would provide 40 000 direct and 48 000 indirect jobs during the construction phase and 46 500 direct and 3 600 indirect jobs over the 20-year operational period of SAF production plants.”

Nationwide SAF supply chains, too, could create nearly 7 500 truck-driver jobs and over 800 support jobs. “About 3 800 of the truck-driver jobs are in coal-mining regions and have the potential to offset almost all coal-hauling jobs that might be lost in the energy transition, as well as preserve jobs in truck maintenance and refuelling.”

The feedstocks fuelling future flights

In South Africa, Chireshe said, the largest potential for SAF comes from woody invasive alien plants. Together with garden waste, these are potentially the largest available lignocellulosic feedstocks in the country and could be converted to 1.8 billion to 3 billion litres of SAF annually. “Aligning government programmes, which are focused on clearing invasive alien plants, such as Working for Water, with SAF supply chains could lower feedstock acquisition costs and hence the cost.”

Solaris, a nicotine-free tobacco variety specifically developed to maximise oilseed production, has been successfully grown in South Africa and could produce 1.1 billion litres of SAF annually and create nearly 20 000 agricultural jobs. When SAA conducted the first SAF flights in Africa in 2016, the SAF used, while made in the United States, was produced from locally-grown Solaris seeds.

Tobacco plantations

Tobacco plantations

Over 300 million litres of A-molasses, a co-product of sugar production, could be produced annually at an internationally competitive price.Industrial waste gases rich in carbon monoxide from heavy industry can be used for carbon recycling and the production of third-generation ethanol, which can be further processed into SAF, with 80 to 116 million litres per year.

Strict sustainability criteria

Not all alternative aviation fuels are created equal, the report warns. “Without complying with sustainability criteria, some of these fuels run the risk of achieving only negligible reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Some fuels may even increase emissions, reduce food security from repurposing land dedicated to food production to feedstock production, accelerate deforestation and unsustainable soil and water usage, and infringe on the land-use rights of local communities, among other things.”

“More consumer awareness could help create SAF demand in South Africa from corporate clients or individuals who can afford.” Photo by MICHELE SPATARI/AFP via Getty Images)

“More consumer awareness could help create SAF demand in South Africa from corporate clients or individuals who can afford.” Photo by MICHELE SPATARI/AFP via Getty Images)

That’s why it’s important to safeguard and ensure the integrity of supply chains, Cherishe said. “This can be managed through independent sustainability standards, which certify the sustainability credentials of these alternative fuels. A number of sustainability schemes exist and have a presence in South Africa, with the Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials being considered best in class.”

Promising signs from aviation sector

The biggest challenge to adopting these alternatives for local airlines is that it “currently does not make economic sense”, especially as they recover from the Covid-19 pandemic, he said.

There is a need for incentives or schemes to develop a local SAF market. “More consumer awareness could help create SAF demand in South Africa from corporate clients or individuals who can afford.”

Solaris, a nicotine-free tobacco variety specifically developed to maximise oilseed production, has been successfully grown in South Africa. (Photo by Yamil LAGE / AFP)

Solaris, a nicotine-free tobacco variety specifically developed to maximise oilseed production, has been successfully grown in South Africa. (Photo by Yamil LAGE / AFP)

However, the number of SAF production facilities, either in the planning stages and coming online, has risen. “We have seen more international airlines making voluntary commitments to procure SAF and others have already started offering SAF to clients. We have also seen policy support for SAF in major aviation markets such as Europe and the US.”

A structural shortage of SAF exists on the international market and airlines have made commitments to procure SAF to “cater for their climate conscious travellers” and/or to meet SAF regulations in their home jurisdictions. “A number of these airlines operate in South Africa and would be in a position to fill up with SAF in South Africa and meet their international obligations.”

[/membership]