Ailing power utility Eskom has warned it will have to ramp up load-shedding during the winter months.(Photo: David Harrison/M&G)

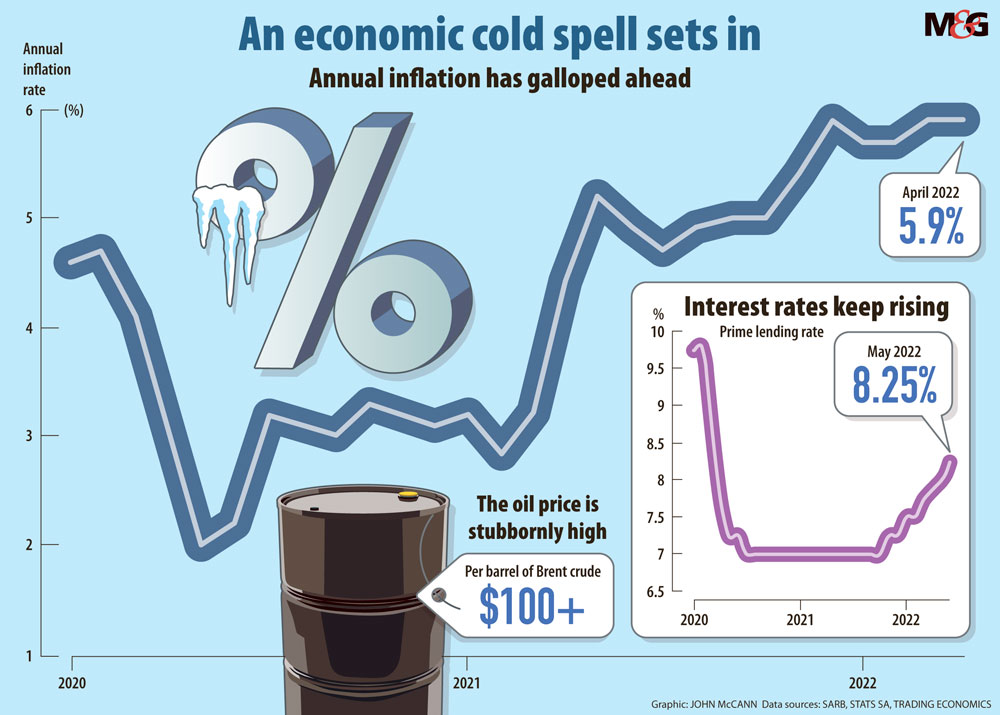

There is a snap in the air, as South Africa faces strong economic headwinds. Russia’s war in Ukraine has sent prices to extreme highs, causing the South African Reserve Bank to raise the cost of debt — and consumers are feeling the chill.

Data showing the depth of the country’s jobs crisis is set to drop next week. With the real unemployment rate having already pushed past 46%, there is little indication that South Africa will have stemmed the tide of job losses.

To avoid higher inflation, the Reserve Bank announced last week that it would raise the repo rate by its highest margin since 2016. The bank’s hawkish stance signalled that more 50 basis point hikes could be on the horizon. And although its governor, Lesetja Kganyago, defended the hike, noting that inflation preys on the pockets of the poor, he immediately faced backlash.

Trade union federation Cosatu and the Economic Freedom Fighters hit out at the decision, arguing that the hike would throw cold water on South Africa’s already glacial economic growth. This fact is borne out in the Reserve Bank’s own projections, which cut the country’s 2022 growth to 1.7% from a previous forecast of 2%.

In its statement, the monetary policy committee noted that short-term factors, such as the devastating floods in KwaZulu-Natal, and long term constraints, like load-shedding, will weigh down South Africa’s GDP in 2022. As the country faces yet another bout of blackouts, the state’s ailing power utility Eskom has warned it will have to ramp up load-shedding during the winter months.

Economy catches cold

What is clear from the Reserve Bank’s appraisal of the country’s economy is that there will be financial pressure on consumers in the coming months.

With no end in sight to Russia’s assault on Ukraine, energy and food prices will remain high. Russia, a major oil exporter, faces a raft of sanctions. The European Union is debating whether to ban Russian oil, which would further constrain the energy market and ratchet up prices.

Fuel inflation, according to the Reserve Bank, could hit 31.2% in 2022, as the oil price holds above $100 a barrel. The cost of petrol has increased by more than 26% compared with a year ago, with warnings that the first week of June will deal yet another major price shock as the R1.50 discount on the general fuel levy falls away.

Meanwhile, elevated fuel prices pose a risk to consumer food price inflation, because a substantial share of agricultural products are transported by road.

The Reserve Bank has revised up local food price inflation to 6.6% in 2022, up from the previous forecast of 6.1%. This is as inflation has caused the price of basic food items to climb. According to April’s household affordability index, the average cost of the food basket increased by R344 (8.2%) compared with the same time last year.

There were significant increases (5% or more) in the price of cooking oil, potatoes, beef, fish, spinach, cabbage, green pepper, tinned pilchards, bananas, polony and apricot jam. The compilers of the index warned that much higher production and logistical costs will continue to drive prices upwards and are likely to continue rising for the rest of 2022.

Middle-income consumers, who, according to a recent warning from FNB are financially stretched, will not be shielded from whatever price shocks lay ahead.

FNB estimates that it takes an average of five days for a middle-income consumer, earning between R180 000 and R500 000 a year, to spend up to 80% of their monthly salary. The bank’s analysis also points out that salaried middle-income consumers spend, on average, 30% of their income on unsecured credit and 35% on secured credit.

A political divide

By hiking the repo rate, the Reserve Bank also increases the cost of this credit, to the benefit of the banks — a fact which is at the heart of the political division on the central bank’s intervention to curb inflation.

“It is a typical left and right debate, whether the interest rate should be high or low,” said Dick Forslund, a senior economist at Alternative Information & Development Centre.

“The reason why this is is because most of the people in the economy, and most of the productive firms, are in debt. And the finance industry is given the credit. So they want the price of money to be as high as possible and all others want it to be as low as possible. And the left usually sides with the majority, the right with the minority.”

Forslund explained the left’s position, which was repeated by Cosatu in a statement after the Reserve Bank’s decision: inflation is being driven by the higher price of imported oil, not by higher demand from South African consumers. Higher interest rates stand to depress demand even further.

If the price of oil increases and the Reserve Bank tries to temper inflation by hiking the interest rate, it could crash the economy, Forslund noted. “They can’t control inflation in the long run by doing this. It is not sustainable.”

But Sanisha Packirisamy, an economist at Momentum Investments, noted that the Reserve Bank is doing well to get ahead of inflation before it starts eating into GDP growth. The Reserve Bank’s new 1.7% growth forecast is now closer to expectations by analysts such as ratings agency S&P Global, which last week raised South Africa’s outlook from stable to positive.

The bank, Packirisamy said, was spooked by the Bureau for Economic Research’s inflation expectation survey. According to the survey, average five-year inflation expectations among analysts, business people and trade unions edged up to 5% from 4.7%, closer to the Reserve Bank’s midpoint target of 4.5%. The five-year inflation expectations tend not to fluctuate based on short-term shocks such as the Russia-induced oil price spike.

“They made quite a statement in the Q&A [after the rates announcement] to say that we shouldn’t be in a position where you allow inflation to run away to unsustainably levels … If you start to hike interest rates when inflation has gotten higher and the horse has bolted, then the impact on growth will be quite severe — because you’d have to hike that much more in order to rein in inflation.”

But, Packirisamy said, it is probably less prudent for the Reserve Bank to continue hiking by 50 basis point increments, considering the economic cost attached to this more severe course of action.

‘Other measures’

Considering the global forces at play, Forslund expects that inflation will continue to choke consumers. “You can expect that it is going to get worse during this year and you can’t beat that by increasing the repo rate through the Reserve Bank. You have to take other measures.”

One such measure would be to scrap the fuel levy. To do so without sinking government revenue, Forslund said, the treasury could consider introducing a wealth tax. By doing so, the government would have greater breadth to roll out a basic income grant, thus increasing demand in the economy.

If the economy continues to be constrained, there is little hope the government will be able to arrest the unemployment crisis. The International Monetary Fund has forecast that South Africa’s official unemployment rate, which stands at 34.9%, will reach 37% in 2023.

Packirisamy noted that South Africa’s GDP growth does not have a one-to-one correlation with employment growth. In previous years, the country would have to see 2% GDP growth for employment to tick up by 1%, she said. “So in that kind of environment, employment growth is still going to be softer than the rate of population growth.”

The repo rate hike means that companies will have less money to spend, making them less amenable to hiring, Cosatu convener Matthew Parks noted. The federation would have preferred a 25 basis point hike, “which would have been less painful”.

On the road ahead for South Africa’s economy, the country’s unemployment crisis and the burden on workers, Parks said: “The trend is worrying and we don’t see the government moving fast enough to address the fundamental obstacles to getting the economy going.”

The government needs to halt the collapse of Eskom, Transnet and the country’s municipalities to unlock economic growth and save jobs, Parks added. “Those are not easy things. But you need to get on top of those big things, or else we are just going to continue to go downwards.”

[/membership]