The decision to form a unity government has been broadly welcomed by economists.

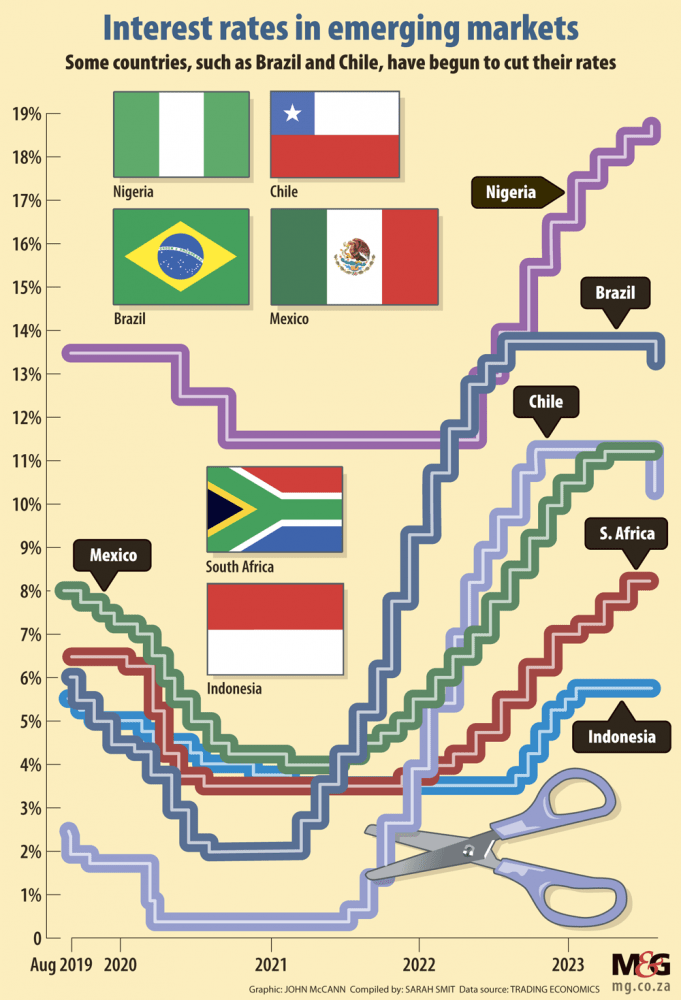

After beating advanced economies to the punch in their fight against inflation, two emerging market countries have started to cut interest rates from their multi-year highs — loosening their vice-like grip on borrowers.

Meanwhile, despite inflation seemingly being on a downward trajectory, South Africans are staring down the prospect of debt costs being kept at their current painfully high levels for some time. This is as the South African Reserve Bank treads carefully, with the country’s energy predicament and the rand’s weakness continuing to pose risks to its inflation outlook.

If the interest rate decisions of other emerging market central banks are anything to go by, it could be many months before the Reserve Bank fires the starting gun on its own interest rate easing.

It took the Central Bank of Chile eight months before its board members took their fingers off pause. Brazil, which followed Chile’s lead, took even longer.

Notwithstanding the Turkish central bank’s unorthodox monetary policy, Chile recently became the first major emerging market to cut its policy rate since the aggressive tightening cycle that gripped much of the world during the latter half of 2021 and in 2022.

In a larger-than-expected move, in late July the Central Bank of Chile reduced interest rates by 100 basis points, marking a welcome reprieve after borrowing costs had climbed to their highest level since November 1998.

The vote to cut Chile’s policy rate was unanimous, with the central bank’s board noting that inflation had fallen faster than expected in June. The bank also flagged continued business and consumer pessimism.

The South American country’s monthly economic activity index (a close proxy for GDP growth) saw its fifth consecutive contraction in June, suggesting that restrictive monetary policy had taken a toll.

The Central Bank of Brazil — which cut its policy rate last week, also by a larger margin than expected — likewise cited easing inflation and the country’s economic decline. The bank reduced the rate to 13.25% from 13.75%, where it had been held for eight months.Despite having the first major central bank to raise its policy rate from pandemic-era lows, Brazil’s inflation soared to 12.13% year-on-year in April 2022, marking the steepest rise in prices in 26 years. After having raised the rate 11 times, starting in March 2021, and holding it at a six-year high, Brazil’s inflation retreated to 3.16% in June of 2023.

Cooling inflation in Latin America comes after central banks in the region opted to “frontload” interest rate hikes, rather than waiting to see whether prices would come down on their own.

Given their history of high inflation, policymakers in emerging markets were less convinced than some of their colleagues in advanced economies that inflation would be transitory.

Brazil’s March 2021 rate hike came nine months before the Bank of England (BoE) began tightening its monetary policy. The US Federal Reserve started lifting rates a year after Brazil did. While the latter central bank seems to have managed to bring inflation to heel — though prices are still above its 2% target — interest rate hikes have been less effective in the UK. UK inflation stood at 7.9% year-on-year in June, well above the BoE’s 2% target.

The South African Reserve Bank also pre-empted rate hikes in the UK and in the US, first lifting the cost of borrowing in November 2021.

At the time, the prospect of tighter monetary policy in the US posed a considerable risk to domestic inflation. The Fed’s decision to eventually lift its policy rate in 2022 led to a period of dollar strength, hitting emerging market currencies, which had experienced something of a hot streak in 2021 amid higher commodity prices.

Currency weakness causes imported prices to rise, applying upward pressure on inflation.

However, South Africa’s inflation — driven mainly by external forces, such as post-pandemic supply-chain bottlenecks and the Russian-induced upward spiral in food and oil prices — did not reach quite the same heights as many of its peers. The country’s annual inflation rate peaked at 7.8% in July 2022, but proved stubborn as the economy reeled from the effects of load-shedding and the ongoing weakness of the rand.

In a sign that prices are finally coming down with some speed, in June South Africa’s annual inflation eased below the 6% ceiling of the Reserve Bank target range for the first time in over a year, pulling back from 6.3% to 5.4%.

After 10 consecutive interest rate hikes, the Reserve Bank’s monetary policy committee (MPC) voted to hold the country’s repo rate at 8.25% in July. As it stands, South Africa’s repo rate is at its highest level since 2009. But analysts don’t expect the MPC to follow July’s decision with a cut anytime soon.

In their report outlining their expectations for South Africa’s economy in the third quarter, Absa economists said their baseline view was that inflation would ease further, briefly slipping below 5% in July, before tracking sideways to end this year at 5%.

They believe the MPC’s hiking cycle is done but said there is a high bar before the committee administers any cuts, given that inflation expectations have drifted higher. They expect the committee will start to cut rates in March next year.

Isaah Mhlanga, chief economist at Rand Merchant Bank, suggested a rate cut could come even further down the line. The bank expects the first rate cut to happen in July 2024.

“We have fiscal risks, which the Reserve Bank has highlighted and which might lead to currency weakness. We still have potential risks to food price inflation from El Niño. Load-shedding. All of these contribute to sticky prices,” Mhlanga said.

“And those are structural. These mean that the Reserve Bank is more likely to stay put before it starts thinking of cutting rates.”

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Local idiosyncrasies, such as the country’s energy crisis, have caused the rand to underperform compared to other emerging market currencies — also affecting inflation.

Pinpointing an emerging market trend is difficult, considering inflation dynamics tend to differ considerably from country to country, Mhlanga added. Sanisha Packirisamy, an economist at Momentum Investments, agreed.

“I think we need to be a bit careful about lumping emerging markets together, because of their different inflation post-pandemic and after the Russian invasion of Ukraine,” Packirisamy said.

“For instance, if you think of our emerging market counterparts in Asia, most didn’t experience very high rates of inflation, because they didn’t necessarily embark on big stimulus programmes post-Covid-19 … So, the dynamics are quite different across the board.”

Packirisamy expects the Reserve Bank will start to cut rates during the second quarter next year, noting that the MPC would be hesitant about cutting rates before the Fed.

“And I think cuts are going to come at a slow pace. They’ll do it in small increments because they will still be looking out for whether disinflation is sustainable … A lot will depend on how fast inflation is coming down but they are unlikely to make massive moves.”