Filling the vacuum: Desperate people from South Africa and its neighbours rework formal mines that have been abandoned or shut down in search of gold-bearing rock. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

There’s no sign of the vendors selling headlamps, knee pads and boots to the illegal artisanal miners in Durban Deep and neighbouring Matholiesville, near the site of the first gold discoveries in the 1880s.

In recent weeks, the police, through Operation Shanela, have clamped down on hotspots of illegal mining in Roodepoort in Gauteng’s West Rand.

“They aren’t here because of the disruption this police operation has caused, but it’s just temporary,” said a resident of Durban Deep, who did not want to be named. “It’s just a PR campaign. The police have got to be seen to be doing something because of the Riverlea protest [over illegal mining]. They did the same last year with the Krugersdorp gang rapes but it never lasts and it isn’t going to last. The will isn’t there … the police are outgunned … and illegal mining is just too big.”

For years, large numbers of illegal artisanal miners have risked their lives in Durban Deep’s abandoned mine by entering portals and ventilation shafts in their search for gold. “The gold is there, people are hungry and the mines are closed,” said the Durban Deep resident

An informal micro-economy has been carved out around illegal mining in the area. “There’s a lot of zama zamas living here that are paying rent to someone, paying for food, gear and women. They have girlfriends with children that they support so there’s an inter-dependency.”

Informal settlements such as Matholiesville have sprung up around informal mining. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Informal settlements such as Matholiesville have sprung up around informal mining. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

This situation is common throughout the Witwatersrand’s goldfields, said Kgothatso Nhlengetwa, an artisanal and small-scale mining expert. Across mining towns where the large-scale mining companies have left, informal settlements have sprung up in “direct result of this zama zama mining”.

She recites a statistic that for every zama zama miner, there are six downstream jobs. This includes those who feed him, supply him with materials, sell him mercury and those who buy the illicit gold.

“That’s why you have this flourishing informal economy. And it’s because there’s no capacity for even law enforcement to clamp down on the actual zama zama mining because they don’t understand the syndicates,” Nhlengetwa said.

“Even when they find the zama zamas and put them in jail, there’s 10, if not 100 more, who will rock up. The punitive measures are put on the poor man on the ground and not on the kingpins.”

In the ruins of these impoverished mining areas, informal supply chains are “feeding the community so the community then ends up liking zama zama miners”, because they can put food on the table as opposed to the ghost towns they previously were.

“They then build this community around zama zama mining and instead of it being based on a formal economy, where large-scale mining companies were there, you find that all the old buildings were stripped for scrap, others were broken down and vandalised, so there’s nothing really left there except for the informal settlement itself,” said Nhlengetwa.

It’s a double-edged sword, she said, because the people who will gain something are the same ones who “then turn around and say but they are actually scaring us or there’s violence in the community”.

Hierarchy: Artisanal miners process the soil in a similar way to the gold panners of the 19th century. The informal miners are at the bottom of the zama zama chain. Regional leaders process the gold further before selling it on to national and international buyers. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Hierarchy: Artisanal miners process the soil in a similar way to the gold panners of the 19th century. The informal miners are at the bottom of the zama zama chain. Regional leaders process the gold further before selling it on to national and international buyers. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Zama zama mining is deeply territorial, marked by violent turf wars. “The communities suffer from the violence, but at the same time they benefit from the activities.”

Illegal artisanal mining in South Africa is among the most lucrative and violent on the African continent, with lost production exceeding R14 billion a year, according to a 2019 report funded by the European Union. It says miners operate in ownerless and disused mines that are “among the most exploitative and dangerous” on the continent.

Artisanal mining is principally carried out underground in industrial shafts, not in open pits, as is normally the case.

“While many ASM [artisanal and small-scale mining] communities navigate a daily combination of unsafe and precarious working conditions, in South Africa, zama zamas are exposed to extortion, murder, forced migration, money laundering, corruption, racketeering, drugs and prostitution,” the report says.

The criminal motives of desperate and destitute illegal miners are vastly different from the motives of those higher up the syndicate ladder. “The lucrative nature of the trade has made murder and pitched gun battles among competing syndicates a frequent occurrence.”

According to Nhlengetwa, about 75% of illegal miners are undocumented migrants from neighbouring African countries, particularly Lesotho, Zimbabwe and Mozambique.

“They are human-trafficked and lured into thinking that there’s better prospects here. They will be told that ‘you’re going to work at a mine’. But when they get here, they get stuck in zama zama mining, which is not what they signed up for.

“There’s nothing they can do to get out of that poverty trap because they have no work. All they can simply do is keep on working. At least it puts something on the table, no matter how violent or dangerous it is [for their] health and safety underground.”

Many, if not most, illegal artisanal miners are former migrant workers, who did not receive their pensions, Unemployment Insurance Fund or other money owed to them upon retirement or retrenchment, said David van Wyk, chief researcher at the nonprofit Bench Marks Foundation.

Hierarchy: Artisanal miners process the soil in a similar way to the gold panners of the 19th century. The informal miners are at the bottom of the zama zama chain. Regional leaders process the gold further before selling it on to national and international buyers. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Hierarchy: Artisanal miners process the soil in a similar way to the gold panners of the 19th century. The informal miners are at the bottom of the zama zama chain. Regional leaders process the gold further before selling it on to national and international buyers. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

“We’re doing research in old migrant labour-sending areas, the places where zamas come from, like Lesotho, and we ask people why they go back. The answers are interesting. They say, ‘We’re going to fetch the pensions of our fathers, brothers and so on that were never paid.’”

For 130 years, Lesotho was underdeveloped because its human resource base was in Gauteng, North West and the Free State. “The economically active people were not there to develop anything so when they go back home after being retrenched there’s nothing there for them,” Van Wyk said.

Illegal mining is on the rise, according to the Strategic Organised Crime Risk Assessment South Africa report by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime of September 2022.

“The decline of South Africa’s mining sector has driven a widespread rise in illegal mining that sees diamonds, gold, platinum and chromium laundered into transnational flows by smelters and syndicates, costing mining companies millions in lost profits and additional security. Violence is widespread, with high levels of extortion and murder.”

In 2018, it was estimated at least a tenth of South Africa’s gold production, with a value of $1 billion, was being stolen each year. “Illegal gold is collected and refined as it passes up the actor chain; most is ultimately sent to Dubai, which is the hub for gold flows from across Africa.”

Efforts to seal off decommissioned shafts have driven a rise in incursions into operational shafts across the country, with an associated increase in corruption. “For gold syndicates to gain access to operational shafts, an entire ‘line’ of employees needs to be paid off, from security guards at the surface to banksmen, winding-engine drivers and miners.”

Gold is like money, and must be washed to bring it into legal circulation, said Willem Els, a senior training coordinator for the Transnational Threats and International Crimes programme at the Institute for Security Studies.

“One method is selling gold to the legal mining houses. They are buying this gold because for them to produce one ounce of gold costs for instance R2 000. For the zama zama, it costs him R500. Now this mine boss can buy this gold for R1 000, but he can produce the same gold for R2 000. So, if he buys it from this guy, he will up his profits and look good to the shareholders.”

The other method is the second-hand jewellery industry, like pawn shops. “What are they doing with the jewellery they buy? They are melting it and then they’re sending it to Dubai. What they do is take zama zama gold, add it to the jewellery gold and say this is secondhand jewellery and we’re exporting it to Dubai. All of a sudden, it’s legal gold.”

Illegal mining is run by organised crime syndicates. “The moment they move into an area, they have to compromise state actors and they start with the police at the lower level. The higher up in the hierarchy, they can compromise these actors, the more they will be protected and the stronger they will become,” Els said.

Tiny Dhlamini, a monitor for Bench Marks in Soweto, said: “The zamas have told me, ‘We are being supplied with guns and phendukas by big shots who own scrap yards, we have policemen and politicians in the high rank’ … It’s a long gravy train and everybody is on the take.”

In March last year, Mineral Resources and Energy Minister Gwede Mantashe gazetted the artisanal and small-scale policy, which reserves artisanal and small-scale mining for South Africans, preventing people from other countries applying for permits.

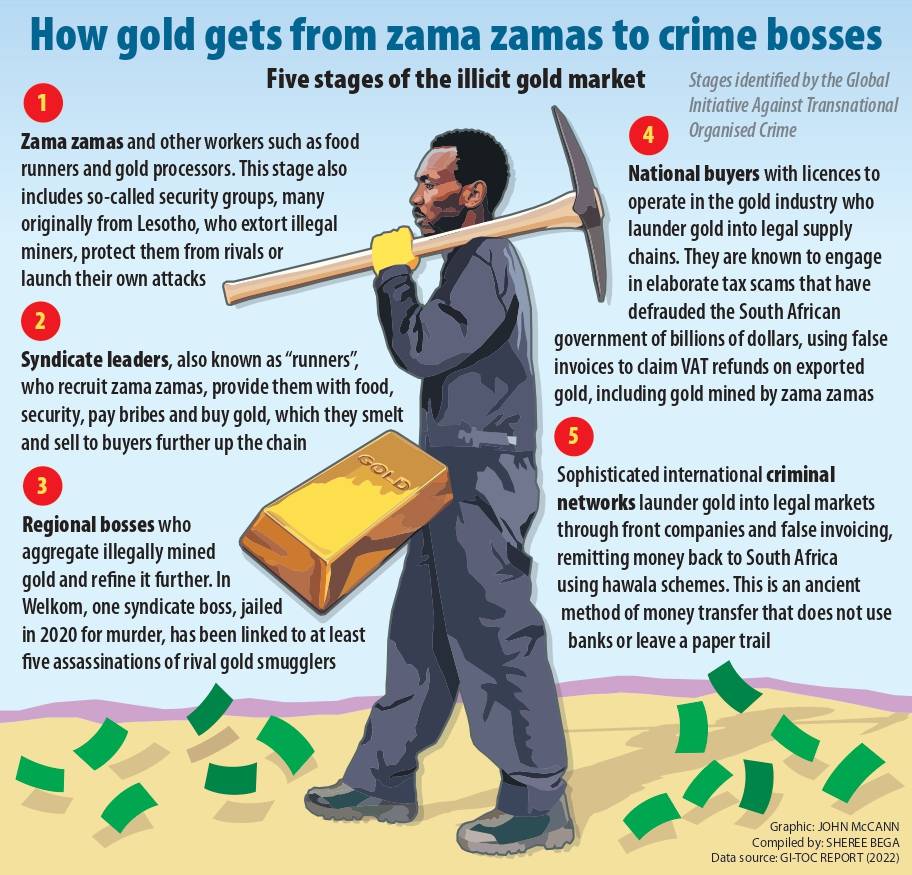

Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

It gives preference to issue permits to co-operatives and not individuals and limits artisanal and small-scale mining to surface and open-cast mining. It proposes the government strengthen laws regarding criminalisation of illegal mining to deter illegal mining activities.

“If you want to create a vacuum for zama zama miners to move from this exploitative syndicate-based zama zama mining, you have to create a space where they can move into and that space has to be inclusionary,” said Nhlengetwa.

“There won’t be a point to formalising artisanal mining because there will be two parallel situations.”

“You’ll have zama zama mining on one side and ASM on the other. That’s why the fact that they don’t include foreign nationals in the permitting process is so problematic … It would be easier for them then to collaborate and get into cooperatives with South Africans and then go out and ask for a mining permit.”

According to the Global Initiative report, the lucrative nature of illegal mining will continue to prove attractive for those willing to face its dangers, especially if formal unemployment rates remain high.

“Legalising small-scale artisanal mining is one possible path, with many arguing that zama zamas are simply artisanal miners who have been frozen out of a sector long dominated by massive corporations.”

But the degree of criminalisation afflicting South Africa’s informal sector is a serious concern. “Either such actors may resist reform as harmful to their influence, or actively support it in order to legitimise their authority and profits.”

Van Wyk said large mines imported labour from Mozambique and Lesotho.

“Why can’t a small-scale operation also use labour from those countries? You just need to regulate the flow of people in and out of the country.”

He noted that Johannesburg started as a squatter camp in 1886.

“Everybody mined exactly the same way as what these guys are mining. Then the randlords came in and they created this super industrial mining complex and all the laws for mining since then have benefitted the big companies. Now the big guys are leaving … because the amount of gold left doesn’t make that kind of capital investment profitable.”

South Africa has failed to plan for a post-mining economy to scale down mining to medium scale, small scale-and survival mining. “That’s what the zama zamas are involved in — survival mining. They don’t drive the BMWs and fancy cars, the syndicate bosses do,” Van Wyk said.

The government allowed mines to collapse, letting valuable mine infrastructure including housing stock, clinics and hospitals, go to ruin.

“This is because we don’t want to solve problems, we abandon problems and they come back to bite us. That’s what we’re seeing now.”