Housing shortage: Several buildings in the central district of Johannesburg are occupied by a large number of people who live in substandard conditions. Photo: Marco Longari/Getty Images

Johannesburg’s economic decay was violently exposed through the tragedy at 80 Albert Street, the site of the fire that claimed 77 lives. In the devastation’s aftermath, politicians laid the blame on civil society, criminal syndicates and an apartheid-created housing crisis.

But, as many have pointed out since, the pass office turned abused women’s shelter-turned-self-contained township also tells the story of the consequence of government neglect.

It also speaks to the way that housing and fiscal policies have betrayed the city, its occupants and the country’s biggest urban economy.

South Africa’s urban housing crisis is part of “a curious legacy”, says Ivan Turok, an urban economist and executive director at the Human Sciences Research Council.

“Central to apartheid was keeping people separate and keeping black people out of the cities — unless they had a job, unless they were useful to employers, in which case they needed a pass.”

Johannesburg’s early image as white and middle class was preserved through apartheid-era legislation, including the Group Areas Act and the Rent Control Act, which excluded black people from living in the inner city.

The apartheid regime’s influx controls, as well as its deliberate restriction on building more housing, constrained urbanisation. The apartheid government’s anti-urbanisation controls became increasingly impractical, given the economic inefficiency of having the country’s labour force kept on the outskirts.

When the post-apartheid government came into power, it sought to meet the country’s housing needs through the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), which aimed to build at least a million decent, affordable and well-located houses in its first five years in government.

But, as Turok has written previously, the housing programme had major drawbacks, one being the location of its project sites.

“The desire to fast-track delivery meant using land parcels that could be developed relatively quickly. This meant taking advantage of sites that were already earmarked for low cost housing by the previous government. Such sites were invariably

on the urban periphery, far from jobs, training colleges and amenities,” Turok wrote in 2020.

A 2014 report by the South African Cities Network noted that the most damning criticism of the housing programme was that it failed to contribute towards the economic transformation of cities. Some of the reasons for this, the report noted, included the high cost of well-located land and inadequate private sector involvement.

Meanwhile, spending on social housing has been constrained — a predicament that stands to worsen the national housing shortfall.

The department of human settlement’s budget only grew at an average rate of 0.1% between the 2019‑20 and 2022-23 financial years. The large majority of that growth came from increases that went towards upgrading informal settlements.

In the medium term, between 2022-23 and 2025-26, the budget for affordable housing projects will only grow at an average rate of 3.2% — well below current inflation estimates for those years.

“The cutbacks in government spending on housing are quite stark,” Turok said.

Hope: In the early years of democracy, RDP houses were built but many sites are on the urban periphery. Photo: Wikus de Wet/Getty Images

Hope: In the early years of democracy, RDP houses were built but many sites are on the urban periphery. Photo: Wikus de Wet/Getty Images

“The government is not building significant numbers of top structures anymore, RDP houses, because of deliberate cutbacks. That is going to make the housing crisis worse. The city doesn’t have the resources to suddenly put more into housing for the poor. They need to be more creative about how they do it.”

Turok’s 2020 paper argues that the government’s housing policy “has tended to stand apart from economic objectives and disciplines, sometimes by design and sometimes by default”.

Speaking to the Mail & Guardian this week, Turok suggested that the post-apartheid government inherited a certain anti-urbanisation mindset.

“The Constitution is clear that freedom of movement is a right. But people still feel that the government should control these movements and not just allow anyone to come to the city,” he said.

Turok described this effort to keep certain people out of the city — holding on to its image as the dominion of white-owned businesses — as “pie in the sky”.

“If people are desperate and looking for work, they are going to do whatever they can. We can’t go back to a pass law system,” he said.

When tragedy hit at 80 Albert Street last week, a large part of the criticism, from the part of politicians, was levelled at the Socio-Economic Rights Institute (Seri) for allegedly blocking evictions from Johannesburg’s so-called “hijacked” buildings. This was despite Seri never litigating against the city in relation to this building.

Seri has fought against illegal evictions in the city. In a 2022 report analysing said evictions, the organisation noted that in the past two decades, the Johannesburg government has been heavily focused on regeneration in an attempt to attract commercial investment.

“The focus of these initiatives was largely on the enforcement of by-laws and excluded the reality of the dire need for adequate and affordable accommodation for those residents who found refuge in occupying derelict inner-city buildings,” the report notes.

Seri has also taken on the metro regarding the city government’s efforts to clampdown on informal traders.

In 2013, then Joburg mayor Parks Tau implemented “Operation Clean Sweep” to address, among other things, the hijacking of inner-city buildings, illegal trading and migration. Tau’s intervention was criticised for jeopardising a key source of enterprise in the city. When Herman Mashaba took over as mayor in 2016, he embraced a similar strategy, intensifying raids on hijacked buildings.

Despite this preoccupation with cleaning up Johannesburg to attract investment, the city’s economy isn’t any better off.

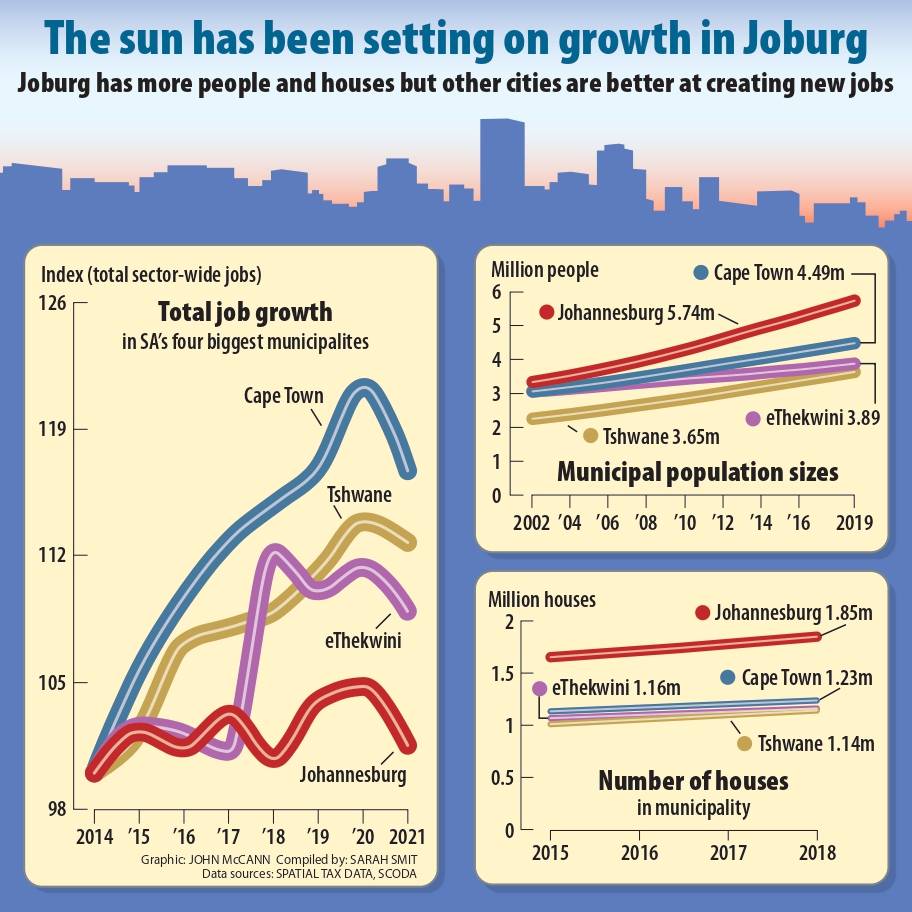

The Cities Economic Outlook, a report that relies on the recently launched spatial economic data, lays bare the city’s economic underperformance from 2014 to 2022. Because metros don’t release their own GDP data — creating a major blind spot for policymakers — the report uses employment as an indicator of economic health.

In contrast to the other big metros, Johannesburg had very weak employment growth, with an increase of only 5% by 2020, translating to less than 1% a year, the report noted. “Given Johannesburg’s status as the country’s largest city and employment hub, its lacklustre performance is very concerning.”

Joburg’s city centre was among the worst-hit by pandemic-era employment losses, the data showed.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

The city’s economy, according to the report, was hindered by the uneven performance of its services sector, which has become skewed towards higher earners in the finance and professional services industries.

Despite weak growth, South Africa’s biggest cities are still attractive, given their higher concentration of job opportunities. The City of Joburg’s population grew at a faster pace than Cape Town, Tshwane and eThekwini from 2002 to 2019.

Duma Gqubule, a research associate at the Social Policy Initiative, said the city’s anti-urbanisation measures are anti-economic.

“People have come here to make a living,” he said. “The big push is internal migration to the cities. People are trying to earn and we should be supporting them to make an income in different ways. I’ve been reading stories about people in Marshalltown. It’s incredible what people are doing and we should be supporting them.”

Johannesburg’s infrastructure, Gqubule said, has simply not kept up with the city’s population growth.

He cited the city’s R300 billion infrastructure backlog — a figure that was set out in the city government’s Golden Report, released to the public in late 2022 by then mayor Mpho Phalatse. The city’s budget is only about R80 billion for the 2023‑24 financial year.

Gqubule called for a heavily subsidised financing model to address the urban housing crisis, which includes direct transfers from the fiscus.

Indeed, Johannesburg’s meagre economic gains have been realised in spite of policies that clamp down on urbanisation and informal trade, as well as the decay of the city’s infrastructure.

Turok said the government has failed to ready its cities for urbanisation, which he says has economic upsides under the right conditions.

“The government has to divert resources towards these fast-growing places, in advance of settlement. There is no good doing it after the buildings have been occupied and when informal settlements have already been created,” he said.

“It’s much more complicated to deal with these problems after they have emerged. It’s much better to plan ahead and prepare for urbanisation. And the government has been really bad at doing that … The government has been very poor at anticipating urbanisation. Rather it resents it and that comes across in some of the comments by politicians.”

China’s economic boom has been attributed to the superpower’s push to accelerate urbanisation, which was a cornerstone of its economic reforms starting in 1978. According to a 2014 book published by the World Bank, China’s urban population stood at less than 20% in 1978. Current World Bank data shows that the percentage of people living in China’s cities reached 64% in 2022.

China’s rapid economic development — which has lifted close to 800 million people out of poverty in the last four decades — “was facilitated by urbanisation that created a supportive environment for growth with abundant labour, cheap land and good infrastructure”, the World Bank book noted. China’s economic reforms also made infrastructure investment a priority.

As Turok contends, if done right, urbanisation can unlock economic opportunities. But the benefits of urbanisation are not automatic, according to the Cities Economic Outlook.

“This is because there are significant costs to agglomeration which demand investment in the built environment for cities to be prosperous and liveable. Transport congestion, overburdened infrastructure, housing shortages, residential segregation and environmental degradation are all symptoms of poorly planned and governed cities,” the report notes.

The important word here is “liveable”. As Turok points out, well-managed urbanisation should ensure that people’s living conditions aren’t so precarious, as they so often are in informal settlements and in the dilapidated buildings of Johannesburg’s inner city.