HelloChoice collects food from Tshwane market that would end up in a landfill. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

It’s early on Monday and Eugene Kriel and his team at SA Harvest’s warehouse in Johannesburg are packing crates of vegetables into their refrigerated truck for delivery to several community-based organisations in Pretoria.

“On Mondays, our donations start coming in and we literally deliver every single day up until Friday,” explained Kriel, the national operations manager for the food rescue and hunger relief organisation.

“We try to ensure that with all the donations that come in, that it is in and out of our warehouse within 24 hours.”

With more than 10.3 million tonnes of edible food wasted annually in South Africa — and 20 million people on the spectrum of food vulnerability — SA Harvest works to “bridge the gap”. Since its inception in 2019, it has delivered more than 47.64 million meals and rescued 214.4 million kilogrammes of food.

The nonprofit rescues food from throughout the food chain — including farmers, manufacturers, distributors and retailers — that would have gone to landfill and delivers it to 216 local organisations feeding hungry people daily. There is a waiting list of more than 900 organisations, Kriel added.

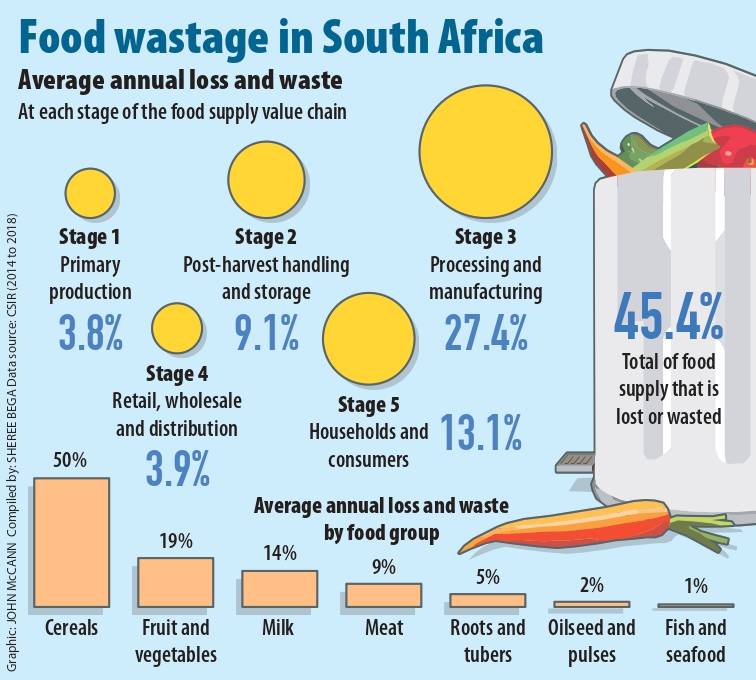

In 2021, a study by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) revealed how an estimated 10.3 million tonnes of edible food, earmarked for people to eat in South Africa, does not reach the human stomach every year. This represents one third of the 31 million tonnes produced annually.

According to the study, the country’s food waste is equivalent to 34% of local food production, but because it is a net exporter of food, the losses and waste are equivalent to 45% of the country’s available food supply. These results, it said, point to high levels of inefficiency in the food value chain, at a time when there is rising food insecurity.

Unspoilt: Eugene Kriel of SA Harvest distributes donated food. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Unspoilt: Eugene Kriel of SA Harvest distributes donated food. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

SA Harvest receives donations of excess, surplus, close to end-of-shelf-life or imperfect products for distribution to food vulnerable people countrywide. To illustrate this, Kriel showed the crates of “imperfect” fresh broccoli, cabbage and carrots in the warehouse’s cold room.

The heads of broccoli were slightly browned. “There is nothing wrong with the actual product, it’s just because it’s ‘sunkissed’ and looks a bit discoloured. But retailers don’t want to accept it because of the colour … so it would just get chucked. It’s sad,” he said.

It’s the same with the carrots and loose cabbages. “They are just odd sizes. They’re either too small or too big. It gets thrown away because there’s no market for it, there’s no consumer that wants it … You must see the sweet potatoes we get from the market. They’re as big as half your arm, but the retailers don’t want it and the restaurants don’t want it.”

In recent months, SA Harvest had “naartjies coming out of our ears”, Kriel said. “ClemenGold donated 10 000 tonnes of citrus to us. All that’s wrong with it is that they had sun stripes so they can’t export it. But it’s perfectly fit for human consumption and some of the nicest naartjies you’ve had in your life. What normally happens is that … they dig a big hole to put it in and they just close it.”

As the SA Harvest truck arrived at one of its beneficiaries, the Basadi Ba Moshito Foundation, a women’s social support centre in Centurion, volunteer Lucia Mokone was waiting to greet it.

“Some of the women that we help, they don’t work and don’t have food to give their families. We make parcels with this food for them to take home. A lot of people are benefitting. It’s a lifesaver for us because veggies are too expensive,” she said.

In Centurion, Coralie Jansen van Rensburg’s nonprofit, Purpose to Feed, nourishes 120 families and is another beneficiary.

Jaco Crafford of HelloChoice collects food from Tshwane market that would end up in a landfill. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Jaco Crafford of HelloChoice collects food from Tshwane market that would end up in a landfill. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

“Food rescue is very important,” she said. “There are a lot of people depending on us. Not even a drop of the food we get is wasted here.”

SA Harvest driver Leslie Mthethwa previously worked in the hospitality industry. “That was for profit, but this is for peace in my heart,” he said. “It is a privilege to see a person in need and then you go there. Some places like Orange Farm, Katlehong, they start to run with the truck when it’s coming, following us to its destination. Sometimes, you find there are hundreds of people and then we’ve got a little food so we give feedback that this place, they need it a little more. Whatever we’ve got, we try to lift it up and you find them so appreciative. That is a good feeling to be the hand that is used to give.”

Wasting food has a triple negative effect, according to the food waste prevention and management guideline for South Africa, produced by the CSIR and the department of forestry, fisheries and the environment.

“It negatively impacts on the economy as all water, electricity, seeds, fertiliser and other inputs used to produce the food is wasted if the food goes to waste,” the guideline notes. “It contributes to food insecurity by increasing the cost of food as the cost of the wastage gets factored into the prices of food, making food unaffordable for poor people.”

Food waste, too, contributes to climate change by increasing greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere. “The decomposition of wasted food disposed of at landfill generates methane, a greenhouse gas that is more effective at trapping heat in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide,” according to the guidelines.

SA Harvest is providing farmers with a solution to effectively manage their excess, surplus or below retail- and export-quality produce by collecting it from the source.

Kriel said: “We just had a meeting with Potato SA and they said that when it’s potato season, some of the farmers burnt, like, 10 000 tonnes of potatoes because it’s just too expensive to try and get it off the farm. That’s why we’re concentrating a lot on the farmers’ level now to actually help the farmers.”

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

As he walked through the Tshwane Market, Jaco Crafford gestured to bags filled with wilting cabbage. “This is the stuff we want to rescue because by tomorrow or a day later, this is going to end up in the landfill.”

Crafford is the national market lead for HelloChoice, which works in partnership with Standard Bank’s OneFarm Share. This is an integrated platform focused on reducing food waste on farms and fresh produce markets, accelerating smallholder farmer development and addressing the pervasive problem of hunger for the country’s most vulnerable people.

OneFarm Share acts as a digital matchmaker, connecting food requests from registered charities to available fresh produce from local farmers and markets.

“We’ve got a limited budget so we try to find as much as we can for the money available. The food rescue project is all about this stuff going to the landfill. We want to get hold of this stock before it gets to that stage,” Crafford said.

“We have pledges with some of these market agents. They said, ‘Listen, you have our commitment to help you with wherever you need at a reasonable price that we can sell for the farmer and we’ll make that available to you.’”

Currently, the Tshwane market is “flooded” with cabbage, he said. “It’s selling slowly. There’s low demand and high supply. So we can come in and say, ‘What have you guys got today for OneFarm Share for R1, R1.50 or R2 a kilo? They will tell us, ‘I can give you cabbage at R25 a bag or I can give you beetroot at R10 a bag, so it’s like R1, R1.50 a kilo, and then we buy the stock,” Crafford said.

Weekly donations are made to food rescue organisations such as SA Harvest and FoodForward SA from the market. “We try to move as much as we can but the funding is limited and these guys can’t make donations, they’re selling on behalf of the farmer, who will say he doesn’t work for free, so we offer them R10 a bag or R20 a bag just to cover some of the costs.”

All food donations receive a Section 18A certificate. “We feel sorry for the farmer for his loss but at least we can feed people with that,” he said. “There are millions of people who don’t know where their next plate of food is coming from.”

There are just too many hungry people to feed. “In some of the soup kitchens in Cape Town, there are rows and rows of people standing with a bucket or a bag to get something, even if it’s just one carrot, or two gems, or two potatoes, or half a loaf of bread. People are desperate out there so if we can make a difference, that’s what we’re going to do.”