Running dry: Residents protest at South Hills reservoir. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

After enduring a crippling 43 days without water, Sonjia Nelson feels as if her life has come to a standstill.

Like many of her neighbours in South Hills, a suburb in the south of Johannesburg, she has had to wake up in the odd hours of the night to check whether there’s any water in her taps so she can do her family’s washing and cook.

“It feels like we’re a community that has been totally abandoned … We get no answers from Rand Water and Johannesburg Water, just the same copy and paste messages,” said a frustrated Nelson, who had joined a group of residents last Friday at the South Hills water tower, all thirsty for answers.

Since August, parts of Johannesburg, Ekurhuleni and Tshwane have battled severe water supply problems, with South Hills and surrounding suburbs among the worst-affected areas. Last Tuesday, Minister of Water and Sanitation Senzo Mchunu met its aggrieved residents.

“We are going to water shift as an interim measure,” he told South Hills residents of the plan to stabilise the system of storage reservoirs that are low by moving water from a system that is doing well to a system that does not have good water levels. “Technicians will be monitoring the system 24/7 as we shift water from systems to systems.”

Nelson said the authorities are failing to grasp the “ripple effect” of the water crisis on residents. “It’s not just that we don’t have water. Emotionally, mentally we’re starting to feel drained … We can no longer cope. This is our basic human right and you can’t take it away from us.”

Ward 56 councillor Michael Crichton agreed. “It’s a bit disappointing that it takes 30 days for something that is a full-blown humanitarian crisis to get someone to take it seriously.”

The area’s water crisis has had an “absolutely horrific” effect on thousands of residents, he added.

“Schools have had to close, and clinics can’t operate. It’s a hygiene problem; it affects your ablution facilities, people … have to wash out of buckets. Then you get your elderly and sickly folks that have to walk kilometres to a water truck — there’s only one water truck per area if you’re lucky — to fill their bucket and then by the time they get home, it could be half empty because the water splashes out of the bucket.”

Alongside Crichton, ward 57 councillor Faeeza Chame also fumed. “This is so inhumane. The worst thing you can do is keep water away from people. There are some people that never saw water the whole week from the truck,” she said. “What about people who are not working who cannot afford to buy water?”

Johannesburg Water said on Wednesday that the South Hills tower system “remains strained due to inconsistent supply” and the tower is on bypass. “Normal pumping into the tower will resume once supply improves. Low-lying areas have been receiving water but with reduced pressure. High-lying areas may still experience poor pressure with no water.”

Nomvula Ndlovu, like many others, must collect water. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Nomvula Ndlovu, like many others, must collect water. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

From her home in Tulisa Park, which neighbours South Hills, Nomvula Ndlovu showed the collection of water containers she has accumulated in the past two years to cope with ongoing water outages. “When my daughter wants to use the toilet, I have to take her to the shopping centre because they have a big water tank. Is that fair? This government is failing us.”

Ward 58 councillor Ricky Nair told how upper Jan Hofmeyer, parts of Mayfair West and Crosby had been without water for 23 days. “In the interim, they [Mayfair West and Crosby] got three hours of water and we rejoiced but then it was gone and now we’re back to square one.”

The water crisis “seems to be getting worse and for longer periods”, he said.

“Filling up your cistern every time you want to use the toilet, to wash is a problem, washing dishes is a problem, having a bath — your geyser doesn’t fill up — and you have to put pots of water on the stove and pour it into a bucket,” Nair said.

“It’s taking me back to my childhood, to the Stone Age times, it’s not on.”

The deputy water and sanitation minister, David Mahlobo, who last week blamed Rand Water and local government for the water crisis, said there are “water supply challenges” in some Gauteng’s municipalities; there is high availability of water in the Integrated Vaal River System.

“There should not be a problem of water availability in Gauteng because some of the municipalities get more water than they are licensed to have. Rand Water is also abstracting and treating more water supplied to Gauteng municipalities than it used to.

“However, there are high percentages of loss of water [non-revenue water] due to water leaks, illegal connections, ageing and vandalism of water infrastructure in municipalities. Water is therefore being lost before it can even reach the communities,” he said.

Ferrial Adam, of citizens network WaterCAN, related how in Greenside, where she lives, every day between 7pm and 7am, water supply has been cut for the past three weeks.

She cited statistics from a parliamentary reply from Mahlobo’s department in June that showed the worst municipalities for water losses in the country were the City of eThekwini with 47% of water produced being lost, the City of Johannesburg with 30%, City of Tshwane with 34%, the City of Ekurhuleni with 33% and Emfuleni with 71% lost.

“My gut feeling is that water distribution in the [City of Johannesburg] municipality is poorly understood and poorly managed and for as long as it’s poorly understood and poorly managed, it’s like fighting in the dark … If we don’t sort ourselves out in the next five years, we’re going to get to a Gauteng where we’re not going to have water.”

The water crisis is “not a consumption issue because 60% to 70% of water is getting lost before it even reaches the consumer”, said Anja du Plessis, an associate professor at Unisa and a specialist in water resource management.

“The reason they [Johannesburg Water] want to blame the consumer is because they only make revenue from the consumer … Now because 60% to 70% is getting lost, they are having a revenue crisis,” she said.

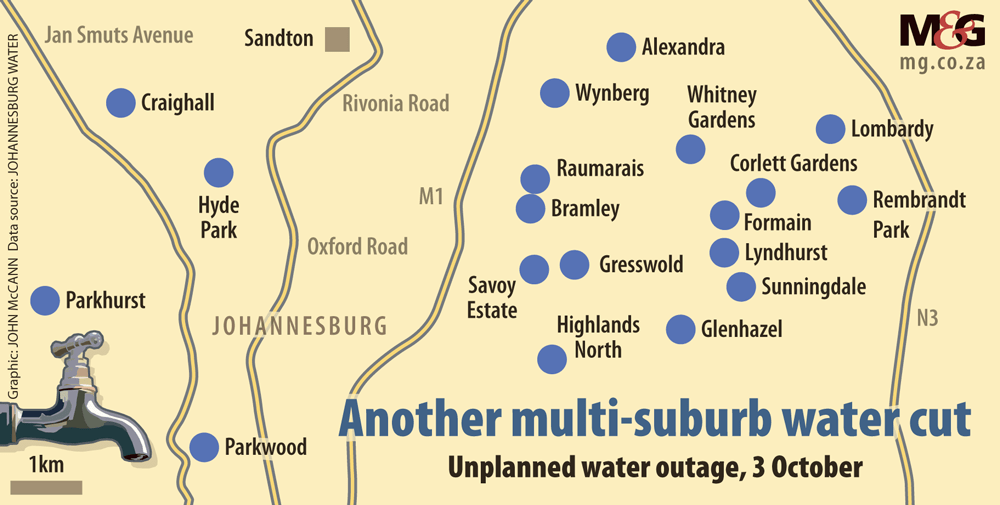

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

On water shifting, Du Plessis said Gauteng’s water reticulation system is not designed to reverse pump water from one pumping station to the next. “You’re now placing more pressure on the Palmiet pump station, which is already almost like Eikenhof, which is struggling with electricity issues and no back-up power, or if there is a back-up pump, the back-up pump is vrot as well.”

Long before the onset of increased temperatures, people were already experiencing water outages.

“As soon as temperatures increased, Johannesburg Water issued multiple statements to say reservoirs are at critical levels. Then the question was asked, how can this happen to so many reservoirs across the whole province within 24 hours? It doesn’t make sense that so many people can empty reservoirs at the same time,” Du Plessis said.

“I see that narrative has now changed after people said it’s not the consumers, it’s the government — they should have done planning, maintenance, upgrading and expansion and they did nothing.”

Even when Phase 2 of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project is implemented, “pipelines from Rand Water towards Johannesburg are only so big and you can only exert so much pressure on those pipelines to ensure that reservoirs are filled”, she said.

“And if you have an air pocket or if your reservoirs are low and your management style is reactive and incorrect … by saying ‘okay, we’re getting water into this reservoir, now we can silence the community by opening this reservoir,’ what happens is that the low-lying people get water … and Joburg Water sends a notification to ‘please decrease your water use because the high-lying areas are not receiving water’,” Du Plessis said.

Instead of closing the reservoir until it has reached a stage where it can build up pressure within the system to ensure that “you’re able to pump water to high-lying areas like Brixton, which hasn’t had water for three weeks, that you know your water levels are at an adequate level … what they’re doing now is just creating a snowball effect”.

Those living in low-lying areas “open up all their taps because they’re so scared they won’t have water the next day,” which then causes over-consumption.

“It’s totally ridiculous that you’re sitting in an African city that was one of the top cities in Africa and one of the notable cities in the world, and with the Vaal system at over 90% [capacity], but people are without water basically due to human negligence and error.”

Du Plessis has not seen any viable plan put on paper, except the provision of water tankers, which “no one trusts after Hammanskraal”.

“You’re not improving people’s quality of life by giving them water tankers. You’re actually degrading it.”