The number of people facing severe food insecurity has increased for a sixth consecutive year, according to the latest Global Report on Food Crisis, with an estimated 15 million more people across sub-Saharan Africa that experienced high levels of acute food insecurity in 2024 than in 2023. (Mohamed Abd El Ghany/Reuters)

Last week, South Africa hosted the G20 Meeting of Agricultural Chief Scientists in Limpopo, ahead of the G20 Leaders’ Summit being hosted in Johannesburg later this year. Senior agricultural scientists and policymakers convened to discuss strategies for mitigating disruptions to global agri-food systems and addressing problems in food access and availability.

The number of people facing severe food insecurity has increased for a sixth consecutive year, according to the latest Global Report on Food Crisis, with an estimated 15 million more people across sub-Saharan Africa that experienced high levels of acute food insecurity in 2024 than in 2023.

Conflict, forcible displacement, extreme weather and economic shocks continued to be the primary drivers of the deteriorating state of food insecurity on the continent. These compounding issues limit opportunities for economic development, worsen environmental degradation and disproportionately affect already vulnerable populations, pushing millions into severe levels of food insecurity.

So far in 2025, ongoing insecurity across the Central Sahel, the Lake Chad Basin and Sudan, alongside high food price inflation continued to drive food insecurity across West and East Africa. In Southern Africa, extreme weather events remained the primary driver of food insecurity in the region with the 2023-24 El Niño being a primary catalyst for high levels of acute food insecurity in parts of Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe, while severe drought led to widespread crop failures and poor vegetation conditions for livestock in areas of Namibia and Zambia.

According to the Intergovern-mental Panel on Climate Change, Southern Africa is one of the most vulnerable regions in the world to climate change because of its physical exposure to weather events, low adaptive capacity and high dependence on climate-sensitive livelihoods.

Moreover, climate-related extreme weather events such as droughts, floods and cyclones, rising temperatures, and erratic precipitation levels are becoming more prevalent and adversely affecting agricultural production, livelihoods and regional food security.

More than 70% of the Southern African Development Community’s (SADC’s) population depends on agriculture for their livelihoods, many of whom live below the poverty line and depend on rainfed agricultural systems for food and income.

The ripple effect of these climate-induced disruptions to agricultural security often leads to loss of incomes for communities, widespread food price volatility and heightened nutritional vulnerability.

These disruptions further deepen socio-economic disparities, disproportionately affecting gender inequalities, and undermine child health outcomes.

Additionally, limited resources, poor infrastructure and weak institutional capacity means many vulnerable people are not effectively equipped to respond to climate-related risks. All these climate-induced disruptions not only pose significant socioeconomic and development problems but also reshape relationships between and within communities, often making social stability more difficult to maintain.

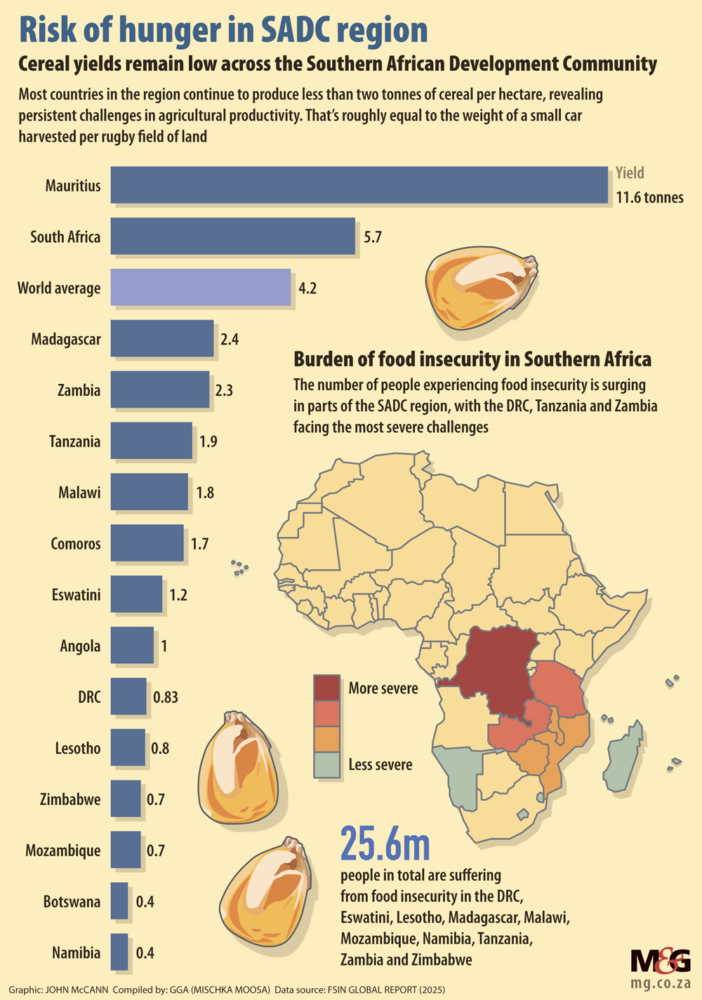

Another factor exacerbating food insecurity in the region is the low level of agricultural production and food system volatility. Agricultural productivity across SADC countries is among some of the lowest globally, highlighting the converging effects of structural constraints, limited investment and access to resilient and inclusive technologies and increasingly prevalent climate shocks.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

These limitations hinder the region’s capacity to build more resilient agriculture food systems and adequately respond to climate variability.

In this way, climate variability and its effects across regional food systems remains overlooked and under prioritised despite its intensifying effect. Bridging these gaps in agricultural productivity and resilience is thus essential for achieving food security in the region, improving livelihoods and fostering inclusive economic development.

Despite these growing effects of climate-related issues to food security, agricultural policy across the region remains reactive, often focusing on emergency response rather than proactive planning.

The SADC approaches issues of food insecurity in the region through the Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan, the Regional Agriculture Policy (RAP) that is operationalised through the Regional Agricultural Investment Plan, and the Regional Food and Nutrition Security Strategy.

In addition, the Malabo Declaration provides the direction for agricultural transformation on the continent for the period 2015-25, within the Framework of the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme.

Together these strategies and frameworks are intended to promote a coordinated response to and development of early-warning systems, data-driven policymaking and multi-sectoral agricultural development and enhancement of food availability, access and stability. Despite their considerations, issues with implementation persist.

Underdeveloped data systems, delayed uptake and prioritisation of fragility analysis and decentralised and poor policy ownership have hindered effective implementation of these frameworks which continue to undermine productive responses in the region.

Policy frameworks also remain poorly aligned with long-term resilience goals, while policy implementation is often limited by problems in regional coordination. Moreover, climate-resilient strategies often lack financial commitments toward adaptation, lack transparency and have limited accountability mechanisms. Finally, the absence of clearer frameworks and stronger regional coordination hinders the ability to consolidate adaptive funding and respond to cross-border threats.

By failing to prioritise the development of resilient agricultural and food systems the SADC’s current approach to climate and agricultural resilience reveals a troubling gap between acknowledgment of the risk and meaningful action. As a result, the consequences of regional inaction on climate-responsive agricultural policy are further exacerbating the already heightened climate fragility faced by the majority of member states.

Addressing these problems requires transformed agricultural production systems and reinforcing climate-resilient food systems by reorienting food systems toward sustainability and inclusivity. Today’s global food networks are deeply interconnected, yet often lack the agility and equity needed to cope with crisis or change.

Additionally current food systems are failing to deliver on adequate nutritional outcomes, sustainability and justice. Despite progress over the past few decades, undernourishment and diet-related threats remain prevalent, while a significant portion of food that is produced is wasted.

Addressing this requires both policy and technological innovation. Interventions such as vertical agriculture, localised community-based food hubs and practices that restore soil health offer the potential to respond to food insecurity, reduce environmental degradation and cultivate community ownership.

In light of this, new policies must prioritise regenerative farming, promote sustainable and inclusive development in the region and support access to equitable and nutritious diets in the region.

Thus, transforming agri-food systems becomes an essential need to meet the growing demand for food in the region while ensuring long-term environmental sustainability. Central to this transformation is included a shift toward sustainable land-use practices, the protection and preservation of biodiversity and soil health and the need for scalable climate-smart practices that enhances the adaptive capacity of food systems, particularly in vulnerable regions.

Additionally, the need to integrate innovative, inclusive and resilient technology in the agricultural sector offers the opportunity for enhanced monitoring and evaluation frameworks and the development of robust early-warning systems to support long-term productivity and climate resilience.

But, if the objectives outlined in the G20 Meeting of Agricultural Chief Scientists are to be actualised in the SADC, then there must be equitable infrastructure and clear, actionable frameworks that support this progress. Crucially, these measures must prioritise the inclusion of the region’s most vulnerable and at-risk populations to ensure the benefit from these advancements are both widespread and sustainable.

Mischka Moosa is a data journalist at Good Governance Africa.