One in 10 clinics in South Africa will start to hand out a twice-a-year anti-HIV jab as early as February. The country’s medicines regulator, Sahpra, says it’s on track to announce its registration decision within the next few days, by the end of October. So who should get LEN first? (Anna-Maria van Niekerk)

One in 10 clinics in South Africa — across 22 health districts in six provinces — could start to hand out a twice-a-year anti-HIV jab as early as February if the country’s medicines regulator approves the shot, called lenacapavir (LEN), soon enough, says the health department.

Boitumelo Semete-Makokotlela, the head of the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority, Sahpra, says the body is on track to announce its registration decision within the next 12 days, by the end of October.

LEN’s manufacturer, Gilead Sciences, submitted data for Sahpra’s approval in March.

Semete-Makokotlela was speaking on a panel at a two-day-long meeting last week organised by South Africa’s Aids Council, Sanac.

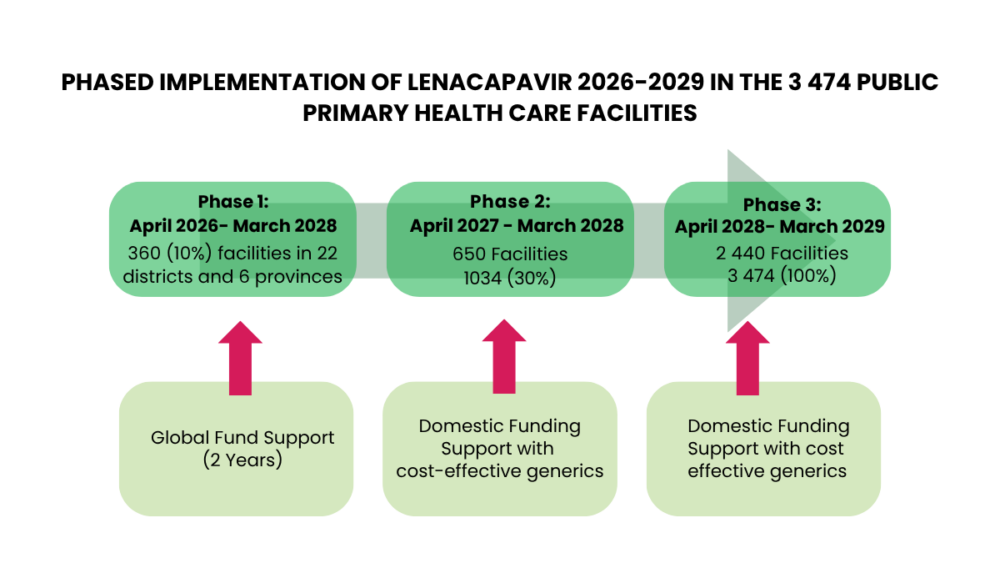

LEN WILL BE ROLLED OUT IN THREE PHASES

So far, LEN, which is injected into the fat under the skin of someone’s tummy once every six months, has been registered as an HIV prevention shot in the US and the EU. The World Health Organisation also “prequalified” the injection last week, a stamp of approval without which donors like the Global Fund for HIV, TB and Malaria can’t help to buy the medicine for countries like South Africa.

If between one and two million HIV-negative people in the country take LEN each year, the shot could stop enough new infections to end Aids in the country within 14 to 18 years, a modelling study presented at the meeting showed.

In 2024, South Africa had 178 000 new HIV infections.

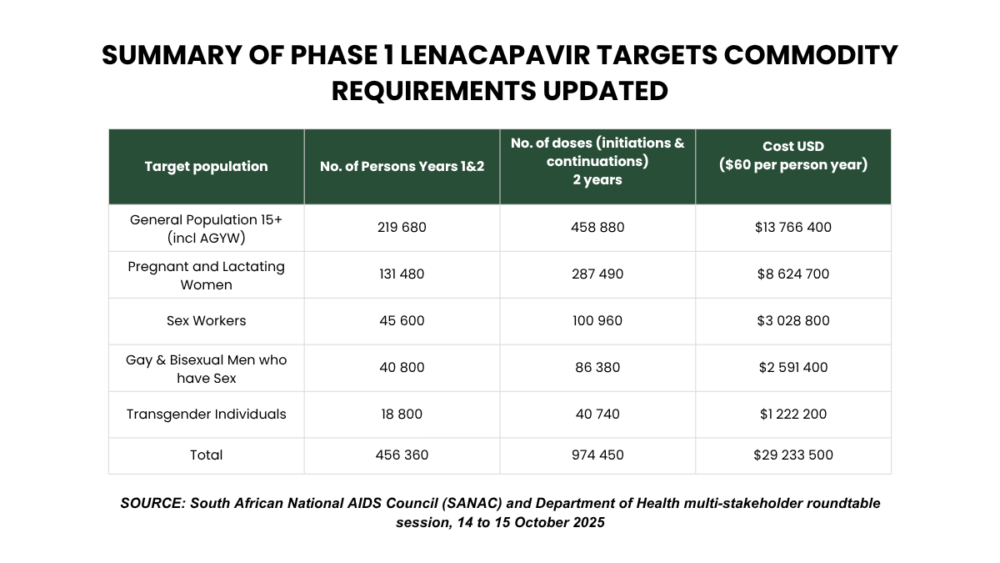

For the first phase of the country’s roll-out, from February/April 2026 to March 2028, South Africa, however, has way too few jabs to be on track to end Aids within the time frame that modelling studies suggest is possible. The country will only have enough doses to phase in 456 360 people on lenacapavir over two years, the health department’s chief director for HIV, Gugu Shabangu, said in a presentation.

GROUPS WHO WILL GET LEN FIRST

The jabs for the first phase — there will be three roll-out phases — will be donated by the Global Fund which is buying the medicine directly from Gilead at an undisclosed price. The health department placed its first order with the fund on September 30.

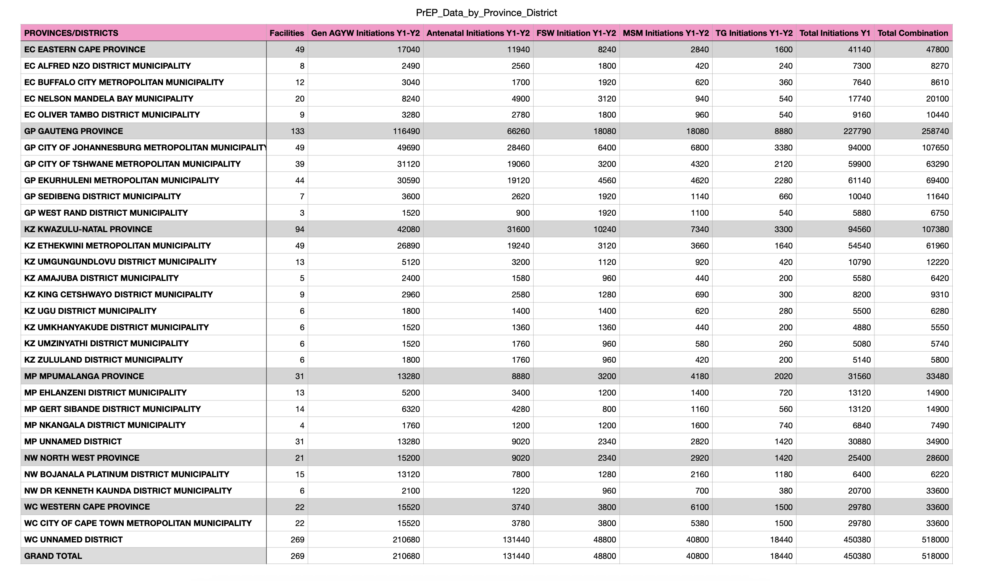

The shots will be stocked by 360 clinics in Gauteng (133), KwaZulu-Natal (94), Eastern Cape (49), Mpumalanga (31), North West (31) and Western Cape (22).

Each of the six provinces has between one and seven health districts with facilities that will hand out LEN. Mostly, those are districts with high rates of new HIV infections and facilities that have been doing well with managing prescriptions for a daily HIV prevention pill that state health facilities started to stock widely in 2020.

DISTRICTS THAT WILL GET LEN FIRST

The Northern Cape, Limpopo and the Free State will have to wait for jabs until phase two of the department’s roll-out, from April 2027 to March 2028, when 650 additional clinics will stock generic LEN bought with government money. Cheaper generics will become available through the course of 2027; at least two drug makers will then sell generic LEN for the same price as the daily pill at around R730 ($40) for a year’s treatment for one person.

During the third phase of its roll-out, between April 2028 and March 2029, all South Africa’s 3 849 primary healthcare clinics will stock the injection.

Should teen girls and young women get the first LEN doses?

For South Africa to get the biggest bang for its buck for the few doses it will have during phase one — so for jabs to stop as many new infections as possible in people who are HIV negative — the injections need to go to groups of people or areas where the chances of people getting infected with the virus are the highest.

Studies show the higher the rate of new HIV infections in a group of people or health district, the fewer the people who need to take LEN to prevent at least one infection. In easy speak, it costs less money to prevent infections in groups where HIV is common, than in populations where HIV is rare, because fewer people would need to take the medication to prevent at least one infection in groups with high rates of new infections.

AARON MOTSOALEDI’S SPEECH

For example, in places where the incidence rate — that is, the rate at which people are getting infected — is 3% or more (some areas in South Africa have high incidence rates like this), around six times fewer HIV-negative people need to take prevention medication to stop one new infection, a study shows, than in places where incidence is low.

“Our approach is firmly data-driven,” Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi explained at last week’s meeting, “using modelling analysis by our local experts, the Health Economics and Epidemiology Office, HE2RO, [at Wits University]”.

But there’s more to calculating who needs to get South Africa’s first LEN doses for the best results than merely looking at which groups of people have the highest rates of new infections, experts say. How easy or difficult it is to reach those populations with information about LEN, and to get the medicine to them in a convenient way, is as important — because it affects how much a roll-out will cost.

In South Africa, for example, teen girls and young women between the ages of 15 and 24 years are contracting HIV much faster than their male peers and many others in the country — four out of every 10 new infections in the country are in this group, even though they make up only about 8% of the total population.

But teen girls and young women are a vast group who are hard to reach because they hang out in many different places, from high schools to TVET colleges to universities to night clubs, shopping centres and work. So, to reach them can be expensive and time-consuming — because health workers would need to travel to so many places to create demand for LEN and let them know how and where to collect the medicine.

When HE2RO’s mathematicians played around with 490 different scenarios of who to give LEN to first, for the biggest impact, they found that giving large numbers of South Africa’s initial stock only to teen girls and young women, would, indeed, not yield the best results.

Should our first doses go to pregnant and breastfeeding women?

Instead, there’s another, smaller group of people with high rates of new infections — pregnant and breastfeeding women — among which the country would be able to prevent more infections with a small number of doses than in teen girls and young women, and for considerably cheaper, HE2RO found.

That’s because almost all pregnant and breastfeeding women visit at least two of the same venues — pregnancy clinics and baby vaccination clinics. So they’re easy to find — and follow up with.

Pregnant women — 27.5% of pregnant women in SA who visit government pregnancy clinics are HIV positive — have a higher chance to contract HIV than the general population, says Dvora Joseph Davey, an associate epidemiology professor at the University of Cape Town, because they often don’t use condoms, as there’s no risk of falling pregnant when they have sex during their pregnancy.

There are also biological reasons why pregnant women are more likely to contract HIV. “When someone is pregnant, there are changes in the cells in the female reproductive system, and the body changes how much of certain proteins it makes, which can cause inflammation,” Joseph Davey says. “Inflamed tissue makes it easier for HIV to enter someone’s cells, because it increases the risk of tearing in the vagina during sex.”

HE2RO’s lead modeller, Lise Jamieson, says giving a large proportion of the country’s Global Fund LEN doses to pregnant and breastfeeding women, means South Africa would also save many babies from getting infected with HIV, the virus can be transmitted from a mother to her baby in the womb, during birth or during breastfeeding.

And, as Yogan Pillay, the head of HIV and TB delivery at the Gates Foundation, pointed out in his presentation, “there’s an overlap between pregnant and breastfeeding women, as many of them fall within the same age range of teen girls and young women”.

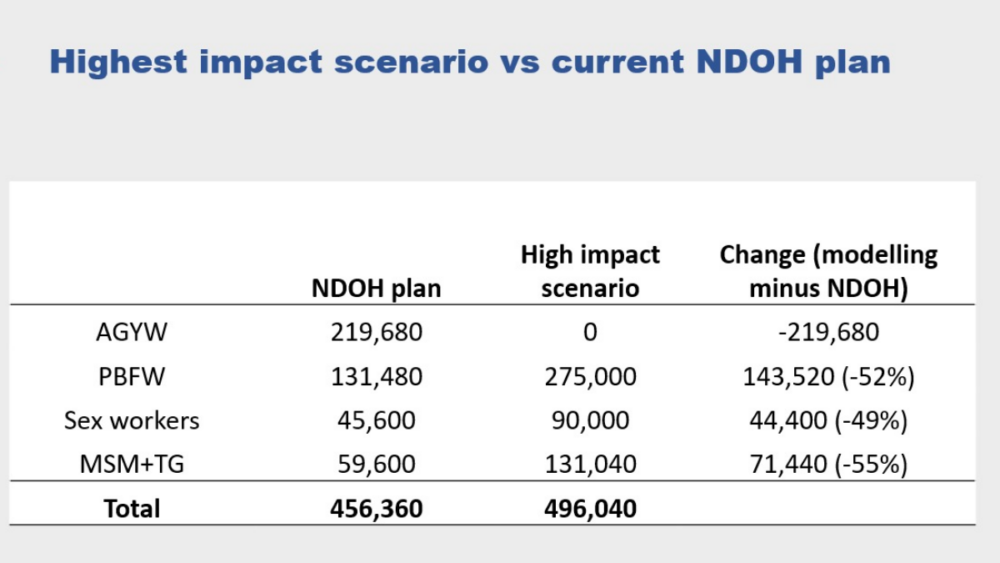

Jamieson and her team found if about 60% — 275 000 — of the initial 456 360 people the country can cover with the Global Fund-sponsored doses are pregnant and breastfeeding women, around 90 000 sex workers and 131 040 gay and bisexual men and transgender people, South Africa will probably stop the highest possible number of new HIV infections — 20 554 between 2026 and 2030. On the other hand, if between 75 and 100% of doses are given to teen girls and young women, only between 5 003 and 7 038 infections would be averted.

Who will the health department give our first LEN doses to?

But the health department’s strategy — at least at this stage — contradicts HE2RO’s findings: 219 680 (48%) of the people covered will be teen girls and young women, as well as the general population; only 131 480 (29%) will be pregnant and breastfeeding women, 45 600 (10%) sex workers and 59 600 (13%) gay and bisexual men and transgender people.

This graphic explains the national health department’s current plan of how to distribute the country’s initial, limited LEN doses, bought by the Global Fund. It compares the plan to HE2RO’s modelling calculations regarding which groups should get LEN to yield the best results, i.e. avert the most HIV infections. (HE2RO, Wits University)

This graphic explains the national health department’s current plan of how to distribute the country’s initial, limited LEN doses, bought by the Global Fund. It compares the plan to HE2RO’s modelling calculations regarding which groups should get LEN to yield the best results, i.e. avert the most HIV infections. (HE2RO, Wits University)

Jamieson says there is room for targeting teen girls and young women and “still have a moderate to high impact” on on curbing new infections, but even in such a scenario, modelling figures show 80% of doses will still need to go towards pregnant and breastfeeding women, gay and bisexual men, transgender people and sex workers.

That’s because, on average, teen girls and young women have lower rates of new infections than pregnant and breastfeeding women, sex workers and gay and bisexual men and transgender people. But Jamieson does point out that there are still subgroups of teen girls and young women — for instance, those who fall pregnant — who have a much higher chance than the group as a whole to get HIV, and those individuals, may benefit from getting LEN.

Bhekisisa contacted the health department 13 times in the past few days to request a copy of Shabangu’s presentation in an effort to get comment from her on the phase one roll-out. All 13 attempts were unsuccessful.

Conference delegates, however, told Bhekisisa the health department discussed the plan with various stakeholders for input, including HE2RO, at the meeting.

Pillay concludes: “Sprinkling LEN will not give us the impact we’re looking for; targeting LEN will do that.

“We need to ask ourselves, ‘Do we want to show early impact on population level by accelerating access to the highest risk and easiest group to reach? Or do we want to focus on equity of access, even for those with moderate risk and who are not easy to reach?’

“If we want to be that ambitious, we will need significantly more resources and we will have to find the resources to do it.”

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.