Topical: Chris Nyathi, left, and Oumi Ndaba in Nyasha Kadandara’s documentary Matabeleland about a

Zimbabwean immigrant’s journey home from South Africa to retrieve his father’s bones. Photo: Supplied

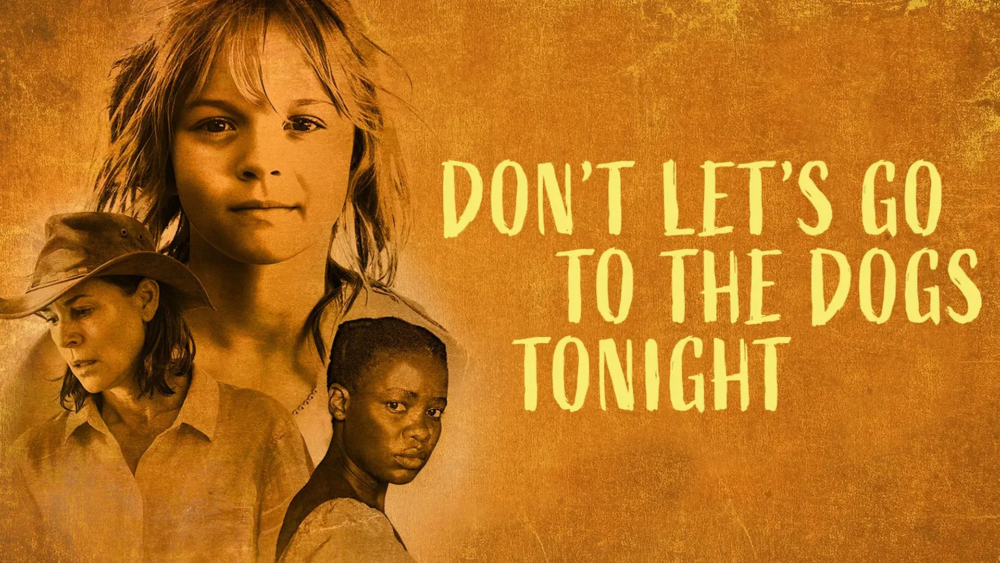

It’s not every day that I leave my neck of the woods to trundle to the other side of London to watch a morning screening in an empty cinema, but I did not want to miss Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight. I’d tried to see it at the Durban Film Festival in July, but couldn’t get in. “But I’m a Zimbabwean!” I pleaded at the reception of the packed Suncoast Cinecentre, but to no avail. The premiere had been sold out for weeks in advance, with Oscar buzz swirling around it.

“Of course it’s got Oscar buzz,” a Black filmmaker friend muttered, “It’s about White farmers.”

Still, I was determined to see it.

Standing in a sea of well-heeled White people, I felt confronted by a wall. Not only could I not get in, but this was not my culture, these were not my people. I didn’t belong here. I grew up in Eighties Zimbabwe and often found myself in mostly White cultural spaces but, somehow, in Durban in 2025, I felt affronted. I imagined many in the audience were former Rhodesians who had emigrated to South Africa when their country did go to the Black dogs – the ‘terrs’ (terrorists) as Alexandra Fuller reminds us the freedom fighters were colloquially called, in her bestselling memoir on which the film is based.

I beat a retreat and hurried to catch up with a small group of Black Zimbabwean colleagues who had gathered for a private screening of another Zimbabwean film in the basement of one of the hotels on the waterfront – Nyasha Kadandara’s documentary Matabeleland about a Zimbabwean immigrant’s journey home from South Africa to retrieve his father’s bones, lost during the massacres of Gukurahundi in the early eighties.

As the #BringBackOurBones campaign comes to a head with Britain’s imminent return of the stolen bones of Ambuya Nehanda, the great leader of the Shona Rebellion against White colonials in the 1890s (also known as the First Chimurenga), a preview of this delicate documentary felt important. And surrounded by Zimbabwean filmmakers, this felt, more appropriately, where I was meant to be.

Yet, when the chance came to see Don’t Let’s Go to Dogs Tonight in London, I rushed from Crystal Palace to Hoxton. I am developing a semi-autobiographical film about my mother, set in the same period – the Zimbabwean War of Independence or Second Chimurenga – so I was keen to see how Embeth Davidtz, the South African actress-turned-director, handled this world. There are so few films about Zimbabwe that I knew this was a rare chance.

To my surprise, Davidtz not only wrote and directed the film but also portrays Fuller’s alcoholic mother, Nicola, with devastating brilliance. Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight is deserving of all the buzz. Davidtz manages to both glamourise and critique Rhodesian society, clearly similar to the White-settler-apartheid culture she grew up with in South Africa.

The glamour: hungover Nicola cuddling her automatic rifle in her tattered negligee as she tries to escape the headache of her noisy children in the morning. The critique: her daughter Bobo’s simple questioning of her mother, “Are we racists?” And Nicola’s denial of what, for the viewer, is all too obvious.

Eight-year-old Lexi Venter delivers a mesmerising performance as Bobo, comparable to twelve-year old Jodhi May’s award-winning offering in Shawn Slovo’s A World Apart in 1989 – ironic that most South African apartheid films were shot in Zimbabwe, and thirty-five years later, Zimbabwe’s struggle is being shot in South Africa in the aftermath of Mugabe’s infamous farm invasions (known by some as the Third Chimurenga).

The detailed production design, stunning cinematography and complex storytelling of a very young person’s observation of her family’s hidden griefs, their complex relationships with their Black workers, and the deluded grandeur of their White poverty surpasses any fiction feature made in Zimbabwe to date. Bobo unwittingly puts her Black nanny at risk of attack as a collaborator while imitating her mother’s airs and graces, but she also transcends the constructs of race with the innocence and clarity that only a child can, giving hope for the country’s promising and hard-won freedom. The acting is superb across the board, the benefits of having an experienced actress as a director very clear.

There’s only one blindspot to Davidtz’ work: the Black South African actors are excellent, but are clearly… South African, with accents and mannerisms that are alien to Black Zimbabweans. When they speak the indigenous Shona language, it is indecipherable as Shona, making the subtitles necessary for even native speakers. In such an authentically detailed production, this came as a shocking disappointment.

As the film progressed, I was able to overcome this discomfort and still be moved by Davidtz’s overall pathos and intention, and in the end, I was inspired by a very worthwhile film. But as a Black-Chinese person, I do not authentically hold the Black Zimbabwean experience: Shona is not my language. I know that viewing the film with a Black Zimbabwean gaze is a different experience.

With that lens, the cultural and linguistic inauthenticity of the Black characters is an affront – like watching Germans playing English with German accents and expecting that to pass with a British audience as representative! And the horror is that only a Zimbabwean would be able to tell. A Western audience wouldn’t know the difference, and perhaps a Rhodesian-now-White-South-African audience wouldn’t care. But a Zimbabwean can’t be fooled, and a Black Zimbabwean viewer cannot genuinely feel included as part of this story.

An affront: Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight is deserving of all the buzz but it does have a blindspot – the South African actors’ accents and

mannerisms. Photo: Supplied

An affront: Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight is deserving of all the buzz but it does have a blindspot – the South African actors’ accents and

mannerisms. Photo: Supplied

Don’t get me wrong: the South African actors are excellently cast for their acting, but the Shona language and cultural consultant on set must have been too kind, or unable to do their job properly. Zimbabweans make up a large part of service staff in South Africa, and there are a number of Zimbabwean actors working in SA – if not the lead Black characters, some of them could have played the supporting roles and helped coach their colleagues. But this was an oversight on the director’s part. While critiquing racism, she fell victim to her own: not all Black people are the same.

I’m taken back to my first encounter with the film: a sea of White people in the foyer of the Suncoast Cinecentre, this feeling that I don’t belong, that this film has not been made for me. And I am sad that this instinct proved true. Sad because Fuller’s story is an important record: the White experience of Zimbabwe is part of our collective history and should be integrated in our evolving culture.

White Zimbabweans in Australia and America deserve to see their experience represented with all the frills of Hollywood, particularly given Davidtz’ intention to observe the culture with a critical eye. And White Zimbabweans, some from historic farming backgrounds, are still an important part of Zimbabwe’s ecology, continuing to contribute to the country in a positive way, even after the traumas of the 2000s.

In the documentary Matabeleland, a key character is Dr Shari Eppel, a clinical psychologist and forensic anthropologist, who helps communities heal by identifying and returning the bones of their loved ones, then supporting families to give them a proper burial. The compassionate actions of this White Zimbabwean woman are some of the most touching parts of the film.

Beyond race, we are all Zimbabweans – Black, White and Brown – on a journey to re-imagine our cultural identity after our dream of a ‘Rainbow Nation’ was shattered by farm invasions and economic collapse, allowing those who thought our country was “going to the dogs” to have the last laugh. It’s unfortunate that Davidtz’s misstep cannot bring Zimbabweans together as a community to commune over a telling of our joint history.

This film is not made for us, but I still applaud its ambition and its success with the White and international audience for which it was made. It’s a South African film. A Hollywood film. And it is for us, Zimbabweans, to tell our own stories.