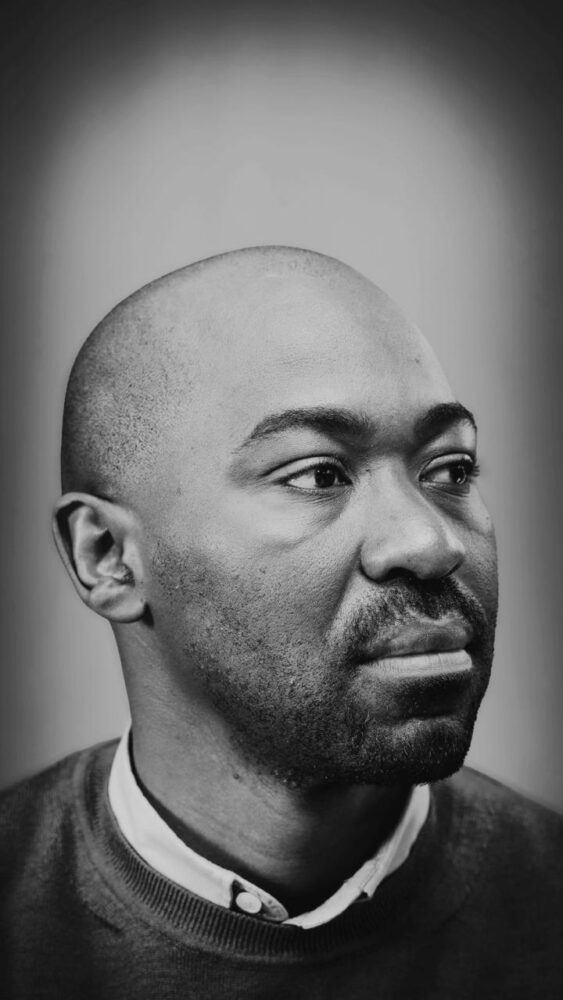

Therapist: Dr Mazibuko says he sees far more women than men in therapy and men often drop out once they feel slightly better. Photo: EQ4 Brand Architects

You would swear Dr Onke Mazibuko is a mathematician in how he explains the writing process for his latest novel, Canary. Or perhaps a mad scientist with a keyboard and stories to prove his hypothesis.

I meet the placid psychologist in Maboneng, Johannesburg, at a trendy restaurant named after one of Miriam Makeba’s hit songs – Pata Pata. In 2022 when he released his debut novel, The Second Verse, the author wasn’t a doctor. The title was brought about by the recent completion of his PhD in Creative Writing at the University of Pretoria – and Canary was part of the coursework.

Unlike the debut novel that took only a few drafts to write, Dr Mazibuko tells me that the creation of Canary involved 12 to 15 drafts. This included a major rewrite after his supervisor found the fifteenth draft too long, resulting in a final 84000-word version driven by a first-person narrative.

“In my frustration I decided I was going to ignore all 15 drafts. I was going to rewrite this thing and see what happened. And when I did that, I wrote about 62000 words. Then I went back to one of the old versions because I really loved those characters.”

It is these numbers that often brought images of Dr Mazibuko mulling over words deep in the night in his secret basement.

True to his profession, Dr Mazibuko wanted to quench his curiosity about the mental health implications of a person being put under highly stressful situations. As such, Canary is a nail-biting psychological thriller about an honest man’s life falling apart for doing the right thing. After years of loyal work for Arms-Tech Industries, Maks Ntaka, the protagonist, has found proof of serious corruption in his department. Maks battles with turning into a whistleblower or staying mum to save his job. Through Maks, the novel examines how corruption, toxic workplace environments and family traumas can have dreadful effects on one’s mental health.

Arriving at first-person narration

Following the publication and validation of his debut novel as Young Adult (YA) fiction, the pressure and comparison to that successful work made writing the next story, Canary, challenging, as Dr Mazibuko struggled with self-editing and perfectionism.

Through compelling characters such as the protagonist, Dr Mazibuko was able to eventually meet that challenge. His use of first narration gives readers an intimate insight into and relatability to a man’s mind trying to toe the line between justice and self-preservation.

Similar to the protagonist, Dr Mazibuko also worked at one of South Africa’s state-owned enterprises for 12 years. Along with the first narration approach, the author’s experience in the procurement department gives the overall story gravitas.

Initially, Dr Mazibuko says, the decision to use the first-person narrative for the Maks’ character was challenging, as he had tried multiple perspectives, including third-person present and past tense.

“I love first-person perspective. One, because I’ve been journaling for most of my life. I am that guy who journals pretty much every day. It felt natural writing that way. But, the psychologist in me is very curious about the mental health of a person in a difficult situation.” Dr Mazibuko says.

The author admits that the initial interest for the novel was not whistleblowing itself, but the psychological pressure it exerts on a person.

“I knew that whistleblowing is a tough situation psychologically. I wanted to put this person under pressure while he’s already dealing with other life problems. So, for me it felt easier to do it in first person narration because I wanted to situate the reader in this protagonist’s head and go everywhere with this person.” Dr Mazibuko emphasises.

Characters, like Maks’ sister Ndileka were easier to write owing to their roles being reduced from previous versions of the manuscript. However, due to Dr Mazibuko having never been a whistleblower during his career, putting Maks’ character on page had some difficulty. Developing Maks’ boss, The General, also proved to be a hurdle.

“The General character was hard because I think the perfectionist in me wasn’t always satisfied with whether he’s evil enough, if he’s charismatic enough and if he is a worthy villain to the hero or not.”

Journalists, whistleblowers

One of the characters I found intriguing was Phumlani Jonas, a journalist with questionable morals who Maks seeks out due to desperation.

“I loved this idea of a journalist that’s got questionable morals but is good at what he does. Nothing seems to work out for him and he’s on his own agenda with a bit of an ego. But he is the kind of character that Maks, probably in other circumstances, would not necessarily spend time with,” Dr Mazibuko adds amongst the rattling of glasses in the back kitchen.

In his research for the novel, Dr Mazibuko was interested in the complicated relationship between journalists and whistleblowers. He argues that journalists prioritise media cycles and shock value over strictly serving the truth.

As our drinks arrive, Dr. Mazibuko referenced the different approaches of whistleblowers citing former Eskom CEO Andre Marinus de Ruyter and former National Security Agency (NSA) intelligence contractor Edward Snowden.

“What was curious to me about both whistleblowers was that Snowden changed the world because of what he revealed about mass surveillance. He had so much evidence that he would release and then every time the government denied and he strategically released evidence over time to maintain relevance. With de Ruyter he dropped the bomb once and thought that it’s going to last in the media cycle but it didn’t.” Dr Mazibuko says as he sips his tea.

These findings, then prompted the author to look at whether the media will assist the protagonist or not if Maks approached a journalist.

Toxic workplaces and mental health

Besides the moral dilemmas faced by Maks, Canary also shows how a hostile workplace environment can negatively weigh on employee productivity and personal well-being. Dr Mazibuko argues that anyone who has been humiliated, alienated and discriminated against in a work environment are signals of a toxic company culture

“You are right up there at management level, but you are put in the basement yet you are qualified. It’s corporate bullying.” he adds as we finish off our lunch.

The novel’s first-person narration of Maks, gives a personal psychological point of view, mostly premised on the author’s twelve years at a state company that was also in question at the Zondo Commission.

The cinematic tone and rhythmic style of the novel also emphasise Mak’s growing mental distress.

“Maks suffers from anxiety and I wanted that to come across in the way the book is written in the sentences. I wanted it to be frantic to almost create this sense of he’s either in a panic state right now. But when he’s feeling depressed, alone, isolated and drinking a lot, the sentences become longer because now he’s stuck in his own head,” Dr Mazibuko confirms.

Sidelined and sabotaged, choking under pressures and morality, Maks is eventually driven to a mental health practitioner.

As a therapist, Dr Mazibuko says he sees far more women than men in therapy and men often drop out once they feel slightly better. He argues that society still views therapy as more acceptable for women, while men who do so may be seen as weak.

“A lot of men are still hesitant due to the stigma of being seen as weak if they go for therapy. But I think that’s coming from an ignorant place where people don’t actually understand mental health issues.” he says.

While at first the themes of corruption and ethical leadership are prominent across the novel, as the story progresses one is met with themes of family dynamics, toxic workplace and mental health issues we carry. As such, Canary is a psychological thriller of how a principled man handles all these troubling themes- whether to run or confront. The novel also gives ode to all whistleblowers grounded on ethical

leadership such as Moss Phakoe, Cynthia Stimpel, Babita Deokaran, Dr Athol Williams including Lieutenant-General Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi.

Ultimately, Dr Onke Mazibuko’s roller-coaster writing process with Canary emphasizes that sometimes less is more in storytelling and the value of external feedback when too much analysis occurs.