The United States’ abduction of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his subsequent transfer to New York to face drug-trafficking charges has inflicted grave damage on the United Nations-centred international legal system that the US largely built. To be sure, President Donald Trump is merely continuing a long history of US interventionism abroad. But whereas previous administrations often paid lip service to human rights or democracy, Trump has taken off the mask. By his own account, America’s mission in Venezuela is to seize control of the world’s largest oil reserves.

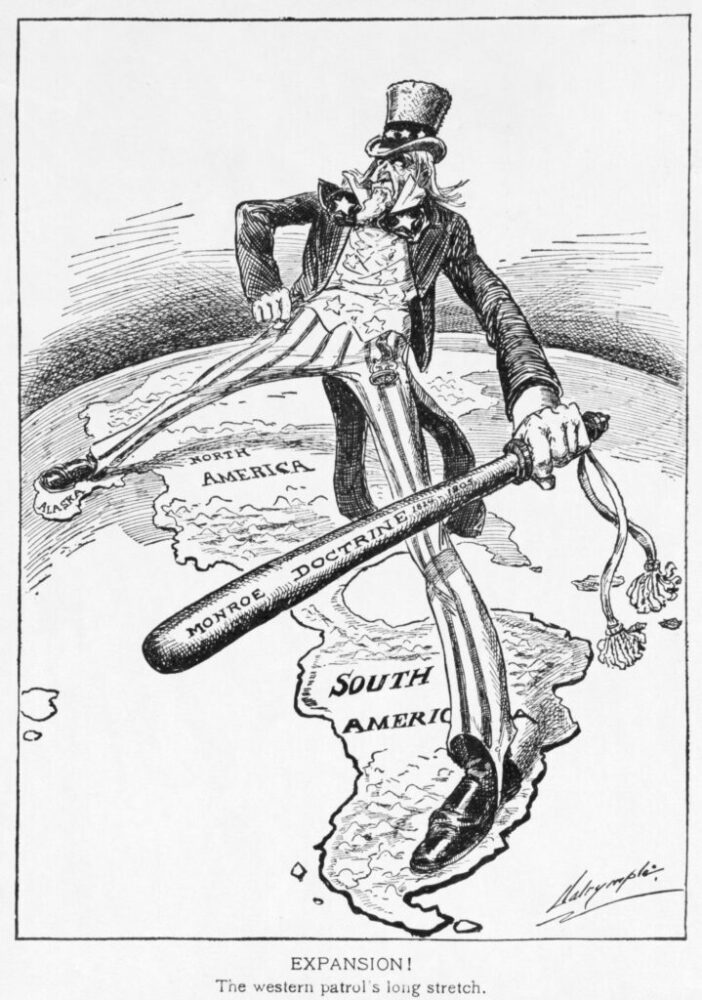

Ironically, the Monroe Doctrine that Trump has dusted off to justify expelling China (which had been buying around 80% of Venezuela’s oil exports) from the Western Hemisphere was actually born of US military weakness. In seeking to bar European colonial powers from its self-declared backyard in the 1820s, the US initially had to rely on policing by Britain’s Royal Navy.

Not until US President Theodore Roosevelt’s 1904 “corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine did the US have the military capabilities to impose its will on the region, which it had already done by expelling Spain in 1898. By then, Pax Americana had come to represent an expansionist project of “gunboat diplomacy” and “Yankee imperialism” in which the US annexed Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, and Puerto Rico, while occupying the Philippines and Cuba. Prior to that, the US had waged war on Mexico in 1846-48, seizing 55% of its territory (today’s California, Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico and Utah).

Similarly, during the Cold War, the US backed vicious military caudillos in Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay and Bolivia, while supporting right-wing death squads and insurgents in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua in the name of anti-Communism. And further afield, in Iran, the US (prodded by Britain) toppled the democratically elected government of Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953, then played a central role in the Belgian-assisted assassination of Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba in 1961.

Two decades later, US President Ronald Reagan’s administration toppled a leftist military government in Grenada. His successor, George H.W. Bush dispatched US Marines to arrest Panama’s military ruler, Manuel Noriega, on drug charges (a striking prequel of Maduro’s abduction).

In 1999, US President Bill Clinton controversially bombed Serbia to the negotiating table without a UN Security Council resolution, while three years later, his successor George W. Bush backed a corporate-led effort to depose Venezuela’s populist leader, Hugo Chávez. But a mass uprising reversed the putsch. The Bush administration then launched its notorious invasion of Iraq (a move opposed even by staunch allies like France and Germany) on the false pretext that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. Since no proper planning had been done for the aftermath, the intervention turned into a bloody quagmire, resulting in an estimated 461,000 Iraqi deaths by 2011.

Finally, the 542 drone strikes launched during Barack Obama’s presidency killed an estimated 3,797 people, mainly in Yemen and Pakistan. In 2011, Obama led the NATO bombing of Libya and though that mission at least had been mandated by the UN Security Council to protect people from slaughter, it soon became a regime-change operation, culminating in the lynching of the country’s dictator. As Obama later explained, “we … had to make sure that Muammar Qaddafi didn’t stay there … Qaddafi had more American blood on his hands than any individual other than Osama bin Laden”.

Obama destroyed Libya as surely as Bush destroyed Iraq. Again, no proper planning had been done for the aftermath of the intervention. The NATO mission left Libya in a state of anarchy. Over the following years, militants and arms spilled out across the already-volatile Sahel, a region that now accounts for over half of all terrorism-related deaths globally.

The US has therefore historically embarked on a perennial quest for foreign enemies: from European imperialists to Latin American Marxists, Soviet Communists, Islamic jihadists and Chinese mercantilists. What distinguishes Trump’s foreign policy from his predecessors’ is his crude and reckless use of military force, his inability to grasp the subtlety of soft power and his wanton destruction of the multilateral institutions and alliances that have sustained America’s global hegemony for eight decades. Trump is also in a class of his own when it comes to flouting the rule of law within the US, engaging in shameless corruption and self-dealing and openly championing a nativist agenda favoured by white supremacists.

The global reaction to Trump’s hubris in Venezuela shows that he has widened the world’s North-South split. Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Cuba, China and South Africa were particularly scathing in condemning the US action during an emergency session of the UN Security Council earlier this month. Even Russia, which has been waging an illegal war of aggression against Ukraine, had the gall to condemn the US with a straight face.

Meanwhile, Europe’s largely muted reaction has once again exposed its spinelessness in the face of a key ally who has gone rogue, just as it did when it condoned Israel’s massacres in Gaza. Yet such hypocrisy is self-defeating because Europe’s craven response to the situations in Gaza and Venezuela will diminish diplomatic support for Ukraine within the UN General Assembly.

And now Europe finds itself confronting US imperialism directly, in the form of Trump’s designs on Greenland. With American imperial aggression fully unmasked, Europeans, like people across the Western Hemisphere, may soon find themselves uttering a version of the 19th-century Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz’s lament: “Poor Mexico, so far from God, so close to the US.” Project Syndicate

Adekeye Adebajo, a professor and a senior research fellow at the University of Pretoria’s Centre for the Advancement of Scholarship, served on UN missions in South Africa, Western Sahara and Iraq. He is the author of The Splendid Tapestry of African Life: Essays on A Resilient Continent, its Diaspora, and the World (Routledge, 2025) and Global Africa: Profiles in Courage, Creativity, and Cruelty (Routledge, 2024). He is also the editor of The Black Atlantic’s Triple Burden: Slavery, Colonialism, and Reparations (Manchester University Press, 2025).