Zimbabwe's President Emmerson Mnangagwa prepares to leave the State House to give his first inaugural address at the parliament in Harare, September 18, 2018. (Photo by Jekesai Njikizana/AFP)

For the last few years the African political landscape has been dominated by high profile changes of leaders and governments. In Angola (2017), Ethiopia (2018), South Africa (2018), Sudan (2019) and Zimbabwe (2018), leadership change promised to bring about not only a new man at the top, but also a new political and economic direction.

But do changes of leaders and governments generate more democratic and responsive governments? The Bertelsmann Transformation Index Africa Report 2020 (BTI), A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems?, suggests that we should be cautious about the prospects for rapid political improvements.

Reviewing developments in 44 countries from 2017 to the start of 2019, the report finds that leadership change results in an initial wave of optimism. But ongoing political challenges and constraints mean that it is often a case of “the more things change the more they stay the same”.

Political change occurs gradually in the vast majority of African countries.

More continuity than change

From 2015 to 2019, the general pattern has been for the continent’s more authoritarian states – such as Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea and Rwanda – to make little progress towards democracy. In some cases countries became incrementally more repressive.

At the same time, many of the continent’s more democratic states – including Botswana, Ghana, Mauritius, Senegal and South Africa – have remained “consolidating” or “defective” democracies. Very few of these dropped out of these categories to become “authoritarian” regimes.

A number of countries have seen more significant changes. But in most cases this did not fundamentally change the character of the political system. For example, Cameroon, Chad, Kenya and Tanzania moved further away from lasting political and economic transformation. Meanwhile Angola, Ethiopia, Sierra Leone and Zimbabwe initially made progress towards it, but these gains were limited – and only lasted for a short period in Ethiopia and Zimbabwe.

As this brief summary suggests, at a continental level the trajectories of different states have by and large cancelled each other out. Positive trends in some cases were wiped out by negative trends in others.

Sub-Saharan Africa as a whole has thus seen no significant changes to the overall level of democracy, economic management and governance. For example, the index shows that between 2018 and 2020, the overall level of democracy declined by just 0.09, a small shift on a 1-10 scale. This suggests continuity not change.

Leadership changes often disappoint

In almost all cases, positive trends were recorded in countries where leadership change generated hope for political renewal and economic reform. This includes Angola, after President José Eduardo dos Santos stepped down in 2017, and Ethiopia, following the rise to power of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. It also includes Zimbabwe, where the transfer of power from Robert Mugabe to Emmerson Mnangagwa was accompanied by promises that the Zanu-PF government would show greater respect for democratic norms and values in future.

Sierra Leone also recorded a significant improvement in performance following the victory of opposition candidate Julius Maada Bio in the presidential election of 2018. Nigeria has continued to make modest but significant gains in economic management since Muhammadu Buhari replaced Goodluck Jonathan as president in 2015.

The significance of leadership change in all of these processes is an important reminder of the extent to which power has been personalised. But it is important to note that events since the end of the period under review in 2019 have cast doubt on the significance of these transitions.

Most notably, continued and in some cases increasing human rights abuses in countries such as Ethiopia, Nigeria, Tanzania and Zimbabwe suggest that we have seen “a changing of the guards” but not a change of political systems.

Nowhere is this more true than Zimbabwe, where the last few weeks have witnessed a brutal government crackdown. Not only have journalists been arrested on flimsy charges, but the rule of law has been manipulated to keep them in jail. Following this sustained attack on democracy, it is now clear that the Mnangagwa government is no more committed to human rights and civil liberties than its predecessor was.

There is no one ‘Africa’

So what does the future hold? I often get asked what direction Africa is heading in. My answer is always the same: where democracy is concerned, there is no one “Africa”. The Bertelsmann Transformation Index report shows how true this is.

In addition to the well-known differences between leading lights like Botswana and entrenched laggards like Rwanda, there is also a profound regional variation that is less well recognised and understood.

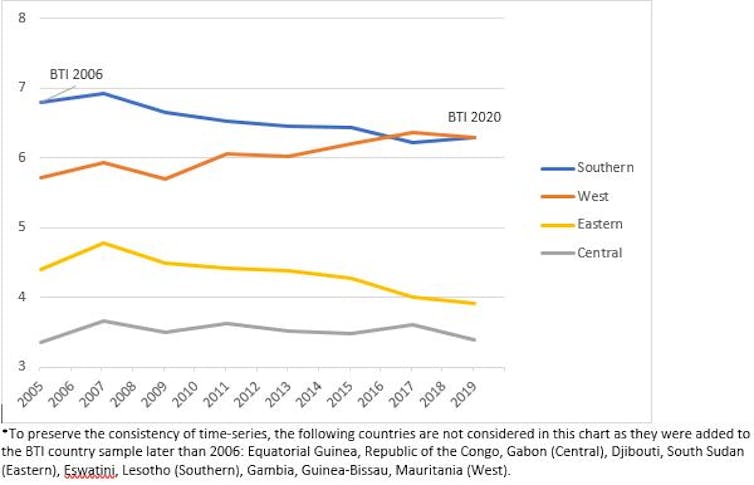

From relatively similar starting points in the early 1990s, there has been a sharp divergence between West and Southern Africa – which have remained comparatively more open and democratic – and Central and Eastern Africa, which remained more closed and authoritarian. There is also some evidence that the average quality of democracy continued to decline in Eastern and Central Africa in the past few years. Because it continues to increase in West Africa, we have seen greater divergence between the two sets of regions.

Figure 1. Average Democracy scores for African regions, BTI 2006-2020*

These variations reflect the historical process through which governments came to power, the kinds of states over which they govern, and the disposition and influence of regional organisations. In particular, East Africa features a number of countries ruled by former rebel armies (Burundi, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Uganda). Here political control is underpinned by coercion and a longstanding suspicion of opposition.

This is also a challenge in some Central African states. Here the added complication of long-running conflicts and political instability (Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo) has undermined government performance in many ways.

A number of former military leaders have also governed West African states, including Ghana, Nigeria and Togo. But the proportion has been lower and some countries, such as Senegal, have a long tradition of plural politics and civilian leadership. In a similar vein, Southern Africa features a number of liberation movements. But in a number of cases these developed out of broad-based movements that valued political participation and civil liberties. Partly as a result, former military or rebel leaders have had a less damaging impact on the prospects for democracy in Southern and West Africa.

It is important not to exaggerate these regional differences. There is great variation within them as well as between them. But, this caveat notwithstanding, we should not expect to see any convergence around a common African democratic experience in the next few years. If anything, the gap between the continent’s most democratic and authoritarian regions is likely to become even wider.

Nic Cheeseman, Professor of Democracy, University of Birmingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.