Seeking refuge: Internally displaced people at the Pemba airport in northern Mozambique wait to be sent to safe areas by the government and international aid organisations earlier this week. (Alfredo Zuniga/AFP)

The raid on Palma in Mozambique proved that no systems were in place to evacuate contract staff in the event of an attack, and Total, as the main contractor, only took responsibility for its staff.

Nobody had a plan for evacuations when the militants attacked Palma on 24 March. The Mozambican authorities still don’t have a centralised system to verify who is unaccounted for, how many were killed and who was to assume responsibility for providing protection to the community and contractors.

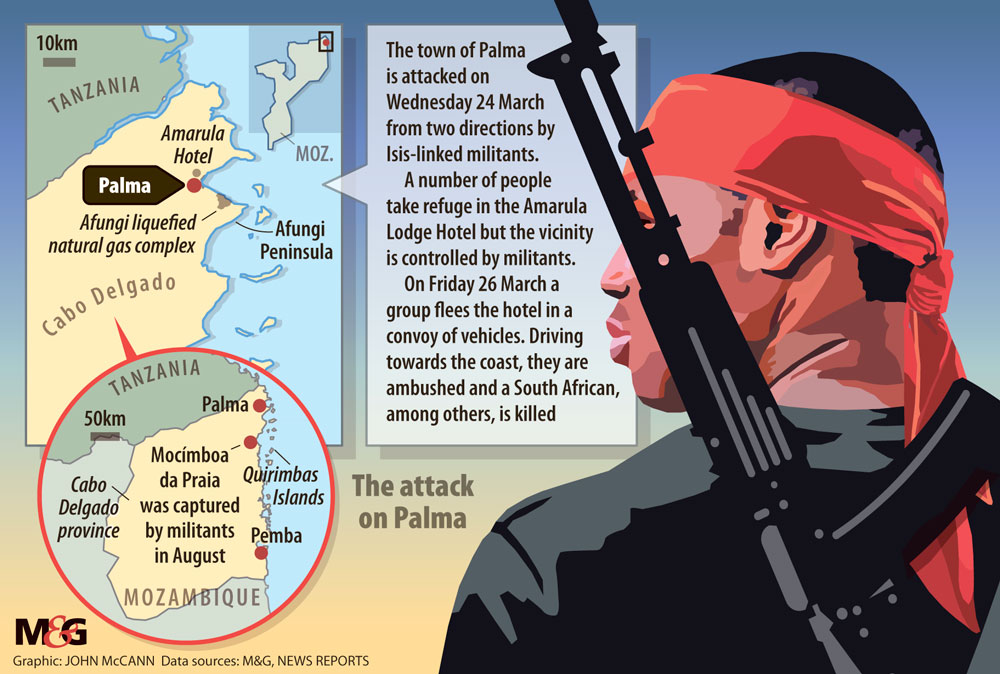

Above all, the Islamic State-related (Isis) attacks on Palma and surrounding villages are a textbook example of how a window of opportunity was used to maximum effect by insurgents when nobody expected them — despite various warnings about imminent attacks.

That was where the situation stood this week while commercial vessels, boats from Pemba and helicopters from the Dyck Advisory Group (DAG) were still picking up the stranded and lost from the beaches north and south of Palma. Palma is the hub of the natural liquefied gas development on the coast of Mozambique where Total has a contract worth $20-billion.

Nongovernmental organisations and volunteers from the Pemba business community were trying to verify conflicting lists of names to determine the lost and found.

Dr Joseph Hanlon, a journalist and development researcher specialising in Mozambique, was this week scathing in his comments about Total’s and the Mozambican government’s handling of the situation in Palma.

“Palma has been under siege for several months, with access roads cut and growing food shortages. Mocimboa da Praia had been cut off in the same way before it was attacked [last year]. Thus, Palma was an obvious target. In the rainy season it is difficult for everyone to move about, including insurgents. The end of the rains — now — is called the fighting season, and the insurgents attacked Palma,” he said.

“There seems to have been no military plan to repulse the attack. The large military force inside the Total construction zone to protect it, remained there to protect workers and not to repel the attack, only moving outside the Total zone on Sunday. There was some fighting from Thursday, but the insurgents appear to have taken control of Palma without major opposition.”

Subcontractors unprotected

Total was subcontracting most of the work in the Afungi gas field close to Palma to some 3 000 expats and local workers. The subcontractors should have known they were going to work in a hostile environment. Instead they were unarmed and left vulnerable when the situation became volatile. Of protection by the Mozambican armed forces (FADM) there was little evidence.

The government recently provided about 1 000 FADM soldiers to protect Afungi from inside the security perimeter, but Palma was outside their area of responsibility. A small contingent of soldiers in the town provided the only security to locals.

The subcontractors were working and living outside the Afungi security zone, and were thus on their own, relying on the FADM to ward off the insurgents when Palma was attacked from three different directions.

The militants first attacked a town on the outskirts of Palma in the few days before the main assault. When the inhabitants started fleeing towards Palma, the fighters donned civilian clothing and bundles and moved among them before regrouping when they reached the town.

Inside their bundles were their weapons and ragtag black and camouflaged uniforms. Images released by the Islamic State’s Central Africa Province (Iscap), together with a statement claiming responsibility for the attack, show the fighters wearing red headbands as they were preparing for the assault.

It was the first time that the red bands were worn and also the first time the militants had used mortars. According to Hanlon, they previously used mostly armaments taken from fleeing FADM soldiers, but the FADM does not have mortars. Apart from sharpening up their training during the rainy season, the militants also obtained new armaments — probably from Tanzania.

Three attacks started at 4pm on Wednesday March 24 and met little resistance. DAG’s helicopters had left the area so the attackers knew there would be no air bombardments. The mobile phone network was cut before they systematically attacked strategic government buildings and the area in town where three banks (including Standard Bank) are.

According to Colonel Lionel Dyck, the founder of DAG, on the first day insurgents went from house to house killing selected people, and it was initially not indiscriminate killing. There were attacks on road traffic, including food lorries, which also affected evacuation. The drivers were decapitated, and their bodies left on the road next to their trucks.

Most of the subcontractors fled to the Amarula Hotel, where most of them were also living, as it had a secure perimeter fence and proper security. About 200 of them were eventually gathered inside. While they were relatively safe, the hotel became a target for the militants as an attack on expats would ensure maximum news coverage.

By late Thursday, the hotel was under siege and the contractors decided to pile everybody into every available vehicle inside the compound to make a dash for the beach.

“We were on the hotel grounds with helicopters to evacuate people, but some claimed there were boats on the beach waiting for them. We had sight of the beaches, we knew there were no boats,” said Dyck.

The moment the convoy left the hotel it came under fire. Seven contractors were killed. The rest scattered on foot; some hid in bushes and others made it to Afungi or at least to the beaches and mangroves to the north and south of Palma.

DAG’s three helicopters picked up more than 200 people in hiding and on the beaches.

“I had asked the Mozambican government to send the air force’s big Mi-8 helicopter as it can evacuate 30 people at a time, where we can only take four per helicopter.” Apart from a brief appearance by Mozambique’s newly acquired Mi-17 and Mi-24 attack helicopters provided by the South African arms manufacturer, Paramount, in Palma “we did not see them again”, said Dyck.

On Monday one of these helicopters were seen taking a media group on a sightseeing trip to Palma, Dyck said, while DAG continued with evacuations and engaging in smaller skirmishes with the militants outside the town. DAG’s contract with the Mozambican police is due to end on 6 April. After that Mozambique will have to take on the full responsibility of air assaults, surveillance, and bombardments, which DAG has been providing in the past year.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

SANDF, SADC and AU?

According to Dyck, South African special forces were prepared to assist in Palma, but the Mozambican government would not allow foreign forces to get involved. Military aircraft would only be allowed to evacuate South Africans. A South African Air Force Hercules C-130 cargo plane left Waterkloof Air Base on Monday and was due to return on Tuesday with South Africans who wanted to return, a message from the SA High Commission in Maputo said.

Any other military assistance would have come too late for the Palma situation — including if one of the SA Navy’s frigates had sailed from Simon’s Town to serve as an offshore command and control centre.

Retired Major General Lawrence Smit, former deputy chief of the army and veteran of various peacekeeping missions by the South African National Defence Force (SANDF), says deploying any South African forces in Mozambique now would not serve any purpose.

“The AU and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) have various mechanisms which have been developed for joint rapid interventions in exactly this type of situation. That includes early warning systems, which are supposed to alert member countries of imminent conflicts. In this case there were no such warnings.”

According to analysts from Willshir & Associates, a terrorism risk and analysis company based in South Africa, proper intelligence from within the conflict area is critical before any military stabilisation intervention can take place. In this case even the host country was seemingly oblivious, as were most of the other SADC countries.

“The SANDF does not even have basic intelligence and surveillance information from Mozambique. The SANDF is also not equipped for guerrilla warfare on the level that the militants in Mozambique operate. One needs a force that can counter the insurgents with the same tactics and that takes considerable skills to develop,” the analysts said.

On Monday Iscap claimed responsibility for the siege of Palma on its Amaq news agency site. It claimed that its fighters had taken control of the town and had killed at least 55 people, including soldiers. On Sunday, the Mozambican defence department said many civilians were killed, as well as seven contractors. The South African department of international relations and cooperation confirmed that all 43 South Africans in Palma have been accounted for, with one death.

The exact death toll will probably never be determined. It was just as impossible a task for a group of volunteers in Pemba to determine exactly who was lost, found or killed as many of those who fled were still making their way back to Afungi. Some were picked up by passing boats travelling along the coast with fresh produce, and commercial vessels.

‘A textbook example’

According to Dyck, the attack was a textbook example of how unprepared those involved in the liquefied natural gas industry were in an area where extremist attacks have become the norm.

“There were no evacuation plans in place despite these companies employing expensive international risk managers to advise them. The precision with which the terrorists planned and executed the attack indicated that they have been planning and preparing for the attacks.

“Total made the mistake to believe the FADM will protect them. We have seen what has happened with the FADM forces in previous skirmishes when they ran away or their weapons were taken. We did not expect them to fare any better soon.”

The exact numbers of people killed, missing or injured have not been released by the Mozambican authorities. More than five days into the “Battle of Palma” random skirmishes were ongoing on the outskirts of Palma and in neighbouring villages.

Total said in a statement this week that it was reducing work on its Afungi site to a strict minimum level.

“The remobilisation of the project that was envisaged last week is obviously now suspended.”

According to Hanlon, prior to the remobilisation President Filipe Nyusi personally assured Total that Mozambique would guarantee security in a 25km cordon around the gas project on the Afungi peninsula. That persuaded Total and the contractors to resume their work.

“Nyusi staked his personal prestige and that of the nation on a promise of security. Total agreed to go back to work. Two days later insurgents occupied Palma, within the security cordon, killing contract staff working on the project. Total says work will only resume when the government really can provide security,” is how Hanlon summarises the situation.

“It was Nyusi’s last roll of the dice. The whole gas gamble was bet on a promise of security, and Nyusi — and Mozambique — lost the bet.”