Side-effects are common when you receive any type of vaccine, a senior vaccine researcher says. (Photo by Michael Ciaglo/Getty Images)

In the 1980s, a factory in Norwood, Massachusetts, churned out Polaroid’s iconic camera film. Polaroid is best-known for its instant camera, which produced a photo that developed before the eyes and within minutes — a revolution in a time when printing photos involved a complicated process of developing the film in almost pitch-black dark rooms. The Polaroid camera captured everything from children’s birthday parties to church fairs for American families that could afford them.

It was a revolutionary technology that transformed photography: memories for the years produced in just minutes.

In photos from the 1980s, workers at the Norwood plant are shown seated at office desks inspecting their finished project. Around them are blue crates of film stacked so high they almost touch the fluorescent ceiling lights.

By 2008, the Norwood plant was just one of two factories still producing Polaroid film, but would soon become a casualty of the world’s shift to digital cameras, and had to close its doors.

But where one technology dies, another springs to life — and many are hoping what is happening now in these premises could help to finally put African countries in control of their Covid-19 vaccine supplies.

Unequal distribution

During the world’s last pandemic (the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, commonly referred to as swine flu), high-income countries able to produce vaccines refused to export them until their domestic needs were met, researchers wrote in 2019 in the journal The Milbank Quarterly.

In the current Covid-19 pandemic, the power to produce a vaccine from its earliest stages still defines which countries have a vaccine and which nations will recover sooner.

By September 2020, countries with local vaccine production such as the US and the UK had secured more than four-billion potential Covid-19 vaccine doses — a figure that would typically account for the world’s total annual vaccine production in the pre-Covid era, says Alain Alsalhani, a vaccines pharmacist for Médecins Sans Frontières’ (MSF) Access Campaign. Today, those countries continue to outpace Africa in Covid-19 vaccinations.

Oxfam recently dubbed the UK ““one of the most vaccinated countries in the world.” The US, meanwhile, has vaccinated at least 14 times more people than the whole of Africa.

The US and most of Europe will reach their Covid-19 vaccine targets by late 2021, The Economist Intelligence Unit predicts. Africa will wait until 2023 to do the same.

More than a decade ago, African countries endorsed a plan to increase their ability to make vaccines and other medicines. Still, only about 10 companies today do any type of vaccine manufacturing on the continent, and much of this has historically been confined to packaging formulated vaccines imported from abroad.

But now, many on the continent — and abroad — are hoping that a relatively new vaccine technology could finally help African countries to take back control of their vaccines supplies — and their epidemics.

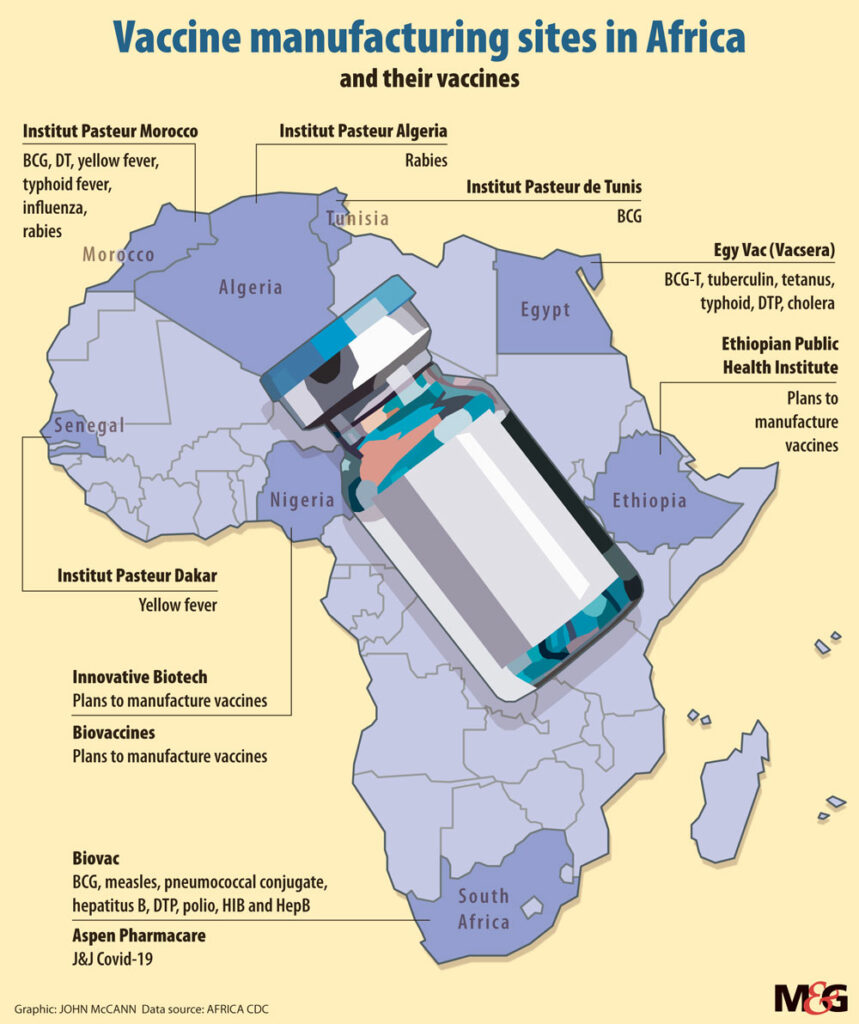

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

A new paradigm

Back in Massachusetts, if Norwood’s old Polaroid plant had helped to pioneer a new age in photography, today it’s at the forefront of another: Messenger ribonucleic acid — or mRNA — vaccines.

When we get sick, our bodies produce antibodies to help to fight off invading germs. Vaccines hope to trick your body into producing these antibodies before you get sick. Usually, jabs do this by introducing a harmless version of a germ — or proteins designed to look like bacteria or a virus — into the body to trick it into producing antibodies.

mRNA vaccines are different. Instead of tricking our body, mRNA vaccines teach our bodies — specifically our cells — how to make the proteins that prompt an antibody response, says the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Although decades in the making, mRNA vaccines made headlines last year after a relatively unknown US biotech firm called Moderna produced an mRNA vaccine to help prevent Covid-19 in less than a year — partly in the old Polaroid factory.

Moderna bought the building and then promptly gutted it: “We only kept the outside walls,” says Moderna chief executive Stéphane Bancel.

In that shell, Moderna installed state-of-the-art ventilation, for instance, to help ensure the plant — and its vaccines — could meet stringent international certification standards. This includes, for example, having designated “clean rooms” where even airflow is carefully contrived to prevent particles in the air from contaminating immunisations. Then built-to-order R288-million bioreactors, or containers used to carry out biochemical reactions, were dropped in. Still, Bancel says that mRNA vaccine production can use bioreactors just a fraction of the size used in conventional vaccine technology.

“In 2019, Moderna was not a commercial company. We were in the early stages of development,” reflects Bancel over a video call from his Massachusetts office surrounded by a U-shaped desk filled with neatly stacked piles of paper. Bancel was speaking at an Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) conference on local vaccine production earlier this week.

“Put that in context: in 2019, we produced 100 000 doses [of our vaccines]. In the first three months of the year, we’ve done 110-million Covid-19 doses,” he says. “Try going to the CEOs of car or mobile-phone companies and telling them that in 12 months’ time they have to make 10 000 [times] more of a product.”

Unconventional wisdom

Moderna’s transformation of an abandoned film factory into a state-of-the-art vaccine manufacturing plant is the reason that many in Africa and abroad think that mRNA vaccine manufacturing might be within the continent’s grasp. For years, the conventional wisdom said that vaccines could be produced only in highly specialised factories, years and millions in the making. But if you can convert an old Polaroid plant in just months, there could be scope to do the same with other types of facilities — with some caveats.

“What we’ve observed in Europe and the US is that companies that have never produced vaccines … were able to repurpose existing capacity and started producing in a matter of four to six months,” Alsalhani says. “So our assumption is that it is potentially much easier to set up production capacity.”

Still, Alsalhani warns that would-be mRNA-vaccine producers in Africa would already probably need to be able to produce goods in ultra sterile conditions, as Aspen Pharmacare in South Africa does.

The Rwandan government is courting a possible mRNA vaccine producer, President Paul Kagame revealed this week. Meanwhile, Moderna’s Bancel confirms he has met several leaders on the continent in recent months, with talks of possibly building a Moderna plant in Africa. Bancel hinted that such a factory could also produce jabs aimed at preventing yellow fever and the mosquito-borne disease chikungunya. Diversifying local vaccine factories’ future production could make local manufacturing more viable.

But experts warn that local production won’t come cheap — or easy. The US bankrolled almost all of Moderna’s Covid-19 vaccine development in exchange for the right to control exports of the vaccine, Achal Prabhala, a fellow at the Shuttleworth Foundation said recently.

Rich countries like the US, UK and Germany invested billions of dollars in vaccine research and development, but public funding does not necessarily lead to public knowledge. Current vaccine makers would still need to be willing to share their knowledge with new producers. But no country that invested in Covid-19 vaccine production made this kind of knowledge sharing, often called technology transfer, a requirement of their funding, at least to the public’s knowledge.

This means that it remains unclear whether any government can compel pharmaceutical companies to share complicated vaccine know-how with new producers, as much as Africa and the world need more Covid-19 vaccine doses.

South Africa is one of just a handful of countries in Africa with any vaccine-manufacturing capacity, and it has taken public-private partnership Biovac almost 20 years to begin producing a vaccine on local soil.

“Raising capital is one of the challenges we faced when we started up,” Biovac chief executive Morena Makhoana says.“The second challenge that we had, but subsequently overcame, is convincing large multinationals to partner with a South African company.”

But these are hurdles that African leaders have indicated a strong willingness to overcome. The example of Moderna and the abandoned Polaroid factory is inspiring the continent to dream big about one day controlling its own vaccine production — and, ultimately, its own destiny.

“We are aware that it is a challenge,” said Africa CDC boss John Nkengasong, at the conclusion of the local vaccine-production meeting on Tuesday. “If Africa does not plan to address its vaccine-security needs today, then we are absolutely setting ourselves [up] for failure.”