A gift to the world from African journalists

The African journalists finalised their definition of press freedom on 3 May 1991. The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) funded and supported the seminar. The United Nations agreed to adopt the Windhoek declaration in 1993 and to declare 3 May World Press Freedom Day.

African journalists at the press freedom seminar in Windhoek, Namibia in 1991 that resulted in the formulation of the Windhoek Declaration.(Courtesy: UNESCO and The Namibian)

African journalists at the press freedom seminar in Windhoek, Namibia in 1991 that resulted in the formulation of the Windhoek Declaration.(Courtesy: UNESCO and The Namibian)

The Declaration speaks of an independent press free from economic and political control, an end to monopolies of any kind and the proliferation of voices reflecting “the widest possible range of opinion within the community”.

Their work will come under the spotlight when UNESCO convened the World Press Freedom Day conference in Namibia on 3 May 2021 under the theme “Information as a Public Good.”

( https://en.unesco.org/commemorations/worldpressfreedomday )

Who were the journalists and media professionals who gathered in Windhoek 30 years ago?

The Journalist with the assistance of researcher Melissa Chetty has crosschecked a list of those journalists who participated in the drafting of the historic document.

The final list of participants is published on these pages. Added to the participant list are South Africa’s Rafiq Rohan and Malawi’s Al Osman, both not on previous lists. The Namibian’s Gwen Lister has forwarded a further four names but by the time we went to print, we were unable to confirm that they were present. They were Fred M’membe of Zambia, Catherine Gicheru of Kenya, Fernando Lima of Mozambique, and Mario Paiva of Angola.

Senior UNESCO expert on Freedom of Expression and Media Development, Dr Guy Berger confirmed that UNESCO was committed to paying tribute to the African journalists who crafted the original declaration. He said that UNESCO has kept occasional contact with a number of them over the years including those who have gone on to other professions.

“We are very pleased that the original co-chair Gwen Lister, is active as one of the co-champions of the Windhoek Declaration today. It is with sadness we heard some years ago that her co-chair of the original event, Pius Njawe, passed away in an automobile accident.”

He further explained that this year’s conference would allow those who follow the events to be able to celebrate the history behind the Declaration.

“On this basis, those involved this year will be party to examining how the original Declaration resonates in today’s conditions. Together they can help shape what current and future generations of journalists and policy-makers, across the whole world, can do to build further upon the legacy of those who met in Windhoek in 1991.”

World press freedom rankings

It is perhaps apt that this world gathering convenes in Namibia since this country has for a number of years ranked highest of all African countries on the Freedom Index.

Last week, on 20 April 2021, the world’s biggest media freedom NGO, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) published its annual Freedom Index that ranks 180 countries according to the levels of freedom available to journalists.

The Index is not an indicator of the quality of journalism in each country. It is a snapshot of media freedom based on the evaluation of pluralism, independence of the media, quality of legislative framework and safety of journalists in each country. Self-censorship and the quality of the infrastructure that supports the production of news and information are also considered.

This year, like last year, six African countries were ranked higher than the United States of America. Following Namibia ranked 24 was Cabo Verde (27), Ghana (30), South Africa (32), Burkina Faso (37) and Botswana (38). The USA ranked 44. Four African countries also ranked higher than the UK (33).

The 2021 Index data reflect a dramatic deterioration in people’s access to information and an increase in obstacles to news coverage. The coronavirus pandemic has been used as grounds to block journalists’ access to information sources and reporting in the field, said the report. The data shows that journalists are finding it increasingly hard to investigate and report sensitive stories, especially in Asia, the Middle East and Europe.

The data further shows that African journalists were hit hard by the coronavirus crisis in 2020, suffering three times as many attacks and arrests from 15 March to 15 May as during the same period the year before. Other violations in the past year on the continent include arbitrary censorship, especially on the Internet (by means of ad hoc Internet cuts in some countries), arrests of journalists on the grounds of combatting cybercrime, fake news or terrorism, and acts of violence against media personnel that usually go completely unpunished.

Elections and protests were often accompanied by abuses against journalists, said the report. The financial weakness of many media outlets made them susceptible to political and financial influence undermining their independence, it said.

Against this backdrop of challenges, the profession will have to seriously assess how far it still has to go to uphold the tenor and tone of the Windhoek Declaration so carefully crafted by these men and women who met 30 years ago. They deserve to be recognised and have their stories fully told in time to come.

*The media fraternity is invited to study the list and contact The Journalist ([email protected]) should anyone have been excluded. Research has shown that a number of those on the list have passed on. This does not mean that an effort must not be made to compile a record of everyone who attended for future generations. If you attended the UNESCO conference: Seminar on Promoting an Independent and Pluralistic African Press at the Safari Hotel in Windhoek in 1991, or know of someone who attended that hasn’t been mentioned in the list, please contact us. — Zubeida Jaffer

For the full conference programme please visit the UNESCO website: https://en.unesco.org/commemorations/worldpressfreedomday/2021/programme

Below is a list of journalists who attended the seminar on promoting an Independent and Pluralistic African Press, Windhoek in 1991 where the Declaration of Windhoek was produced and signed.

Algeria: Omar Belhouchet, Mayouf Zoubir Souissi

Angola: Joaquim Pinto Andrade

Benin: Isma l Yves Soumanou, Thomas Megnassan

Botswana: Methaetsile Leepile

Burkina Faso: Luc Adolphe Tiao

Burundi: Albert Mbonerane

Cameroon: Pius N. Njawe, Paddy Mbawa

Chad: Saleh Kebzabo

Côte d’Ivoire: Issiaka Tao, Paul Arnaud

Democratic Republic of Congo: Léon Moukanda Lunyama

Djibouti: Ismail Tani

France: Sennen Andriamirado, Michel Duteil, Philippe Maeght

Gambia: Sanna Manneh

Ghana: Ajoa Yeboah-Afari, Paul Ansah, John Nyankumah

Guinea: Sankarela Diallo

Guinea-Bissau: Francisco Barreto De Carvalho

Kenya: Mohamed Amin, George Odiko, Stephen Musalia Mwenesi

Lesotho: Mike Pitso

Liberia: Kenneth Yakpawolo Best

Madagascar: Rahaga Ramaholimihaso

Malawi: Janet Zeenat Karim, Al Osman

Mauritius: Gérard Cateaux

Namibia: Gwen Lister

Niger: Ibrahim Cheick Diop

Nigeria: Sam Amuka, Lewis Obi, Kaye Whiteman

Senegal: Abdoulaye Bamba Diallo

Sierra Leone: Paul Kamara

South Africa, Rory Wilson, Anton Harber, Rafiq Rohan

Sudan: Bona Malwal

Swaziland: Sabelo Gabriel Nxumalo

Tanzania: Fili Karashani

Togo: Komi Agah, Vincent Traoré

Tunisia: Ismail Boulahia, Salah Fourti, Mohamed Ben Salah

Uganda: Alfred Okware, Aloysius Bbosa, James Namakajo

United Kingdom: Shamlal Puri, Alan Rake

United States of America: Dennis Schick

Zambia: Francis Kasoma, Goodwin Mwangilwa

Zimbabwe: Geoffrey Takawira Chada, Onesimo Makani-Kabweza, Hugh Lewin, Andrew Moyse, Geoffrey Nyarota, Govin Reddy

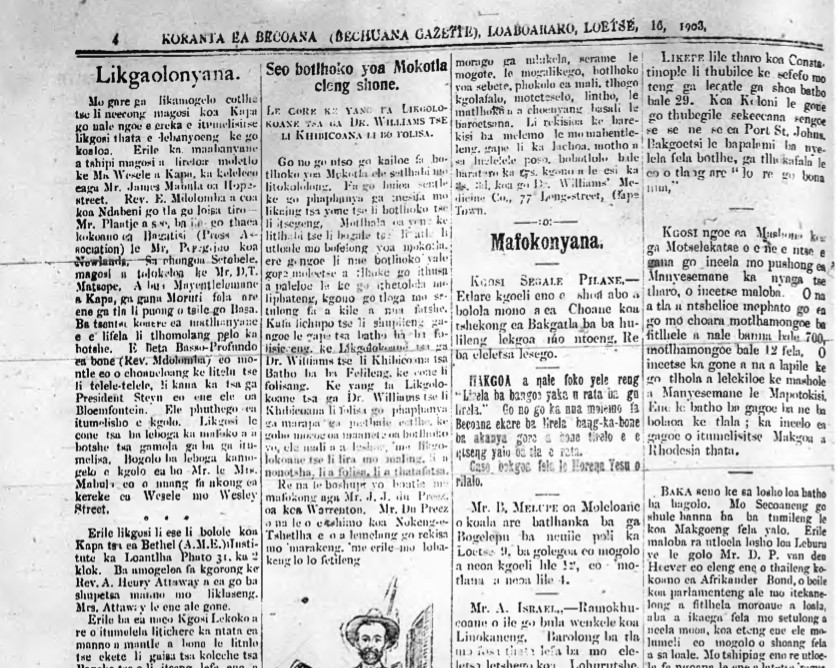

Sol T Plaatje: Pariah In the Land of His Birth

Solomon Tshekiso Plaatje was a journalist extraordinaire. He was by all accounts the pioneer of pioneers. We take him as “exemplar and standard”, said former Education Minister Professor Kader Asmal in the foreword to Native Life in South Africa, the 1916 Plaatje classic republished in 2007.

Politician, author, translator, newspaper editor Sol Plaatje.

(Courtesy: Wits University Press)

Politician, author, translator, newspaper editor Sol Plaatje.

(Courtesy: Wits University Press)

“It reminds us that this country needs more Sol Plaatjes, more crusading journalists who use language like a rapier, not a sledgehammer, who know their stuff and argue their case on the basis of justice, reason and the facts,” said Asmal.

Plaatje, a largely self-taught man, could speak seven languages fluently. He translated William Shakespeare’s works into Setswana and collected African folklore and proverbs. He was a pioneer of journalism in our indigenous languages but wrote extensively in English as well. He defended tirelessly the rights of African people.

On the Warpath With A Pen

Plaatje was born in the Boshof District of the Orange Free State in 1876. His parents – Johannes and Martha Plaatje – were Christians who worked for the missionaries. When he was born, they named him Thekiso, a Tswana name meaning that which you do for advantage or gain. His parents were signalling that he needed to seek advantage for himself and his people and so he did.

In his lifetime, Plaatje moved seamlessly from interviewing homeless people by the roadside to a meeting with the British Prime Minister. He gave talks and showed films at local schools and community centres. He once shared a podium with Marcus Garvey, the famous Jamaican ideologue who propagated the unification and empowerment of all Africans, even those in the diaspora.

As editor of the black-owned newspapers, Koranta ea Becoana (1901–1908) and Tsala ea Batho (1910–1915), Plaatje highlighted issues of great concern to Africans such as racism, injustice and exploitation.

When the Land Act of 1913 was passed, he used his pen to go on the warpath. He travelled around the country on a bicycle to research the effects of the new legislation. His work was published in 1916 as the famous classic, Native Life in South Africa. He meticulously reported on conditions around the country, leaving us with first-hand accounts of the early years of dispossession.

The opening words of the first chapter of this book, have become immortalised:

“Awaking on Friday morning, June 20, 1913, the South African native found himself, not actually a slave, but a pariah in the land of his birth.”

Later he wrote:

“For to crown all our calamities, South Africa has by law ceased to be the home of any of her native children whose skins are dyed with a hue that does not conform to the regulation hue. “

Plaatje’s pen raised his national profile. He became the first Secretary-General and founding member of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC) in 1912.

Rise of Protest Journalism

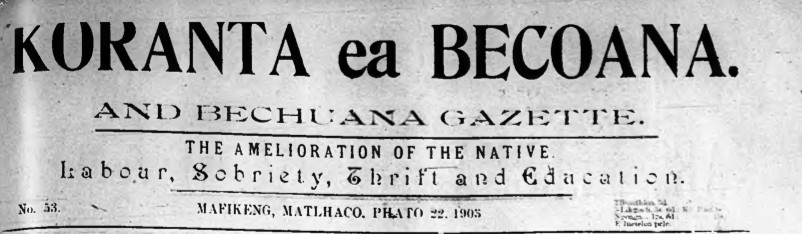

Reading the digitised editions of Koranta gives you a powerful glimpse into the world of Sol T Plaatje. At first glance, the masthead of Koranta ea Becoana seems like information for a tasteless self-help book. Beneath the name it states: The Amelioration of the Native – Labour, Sobriety, Thrift and Education.

But as you scroll down, you encounter the richness and contradictions. On the first pages colonial merchants vied with each other. Some sold bicycles, some medicine – like Hoffe’s remedy. If we can believe the advert, this remedy cured and prevented fever and was never known to fail. In true merchant bravura, some colonials offered their “selling skills”.

A story about the influential Barolong people who were seeking compensation from Imperial Britain in 1903, went to the heart of the issues of the day. Colonel Baden-Powell enlisted the Rolong to fight alongside the British in the Anglo-Boer War. Baden-Powell promised that compensation would follow, but this did not happen. To this day, the Rolong haven’t been compensated or even acknowledged.

Koranta, like other newspapers of that time, was modest in size and moderate in tone, with low circulation rates among a population with limited literacy. Yet they confronted a social system that discriminated against all.

Originally established by the editor of the Mafikeng Mail, G.H. Whales, Koranta began as a one-page newsletter supplement in Tswana with an initial circulation of 500. Silas Molema, of the prominent Barolong people, bought the paper from Whales to make way for Plaatje as Editor.

Koranta covered the issues of the day that affected Africans

Koranta covered the issues of the day that affected Africans

When Plaatje became Editor he increased it to two pages, appointed newsagents and solicited advertisements. By the end of 1902, Koranta was an eight-page title with a circulation of 2 000 nationwide. By the following year Molema and Plaatje set up a printing plant and built an office in Mafikeng. But his success with the paper was more than just operational. Koranta and subsequently Tsala ea Becoana were politically influential.

In several issues of the paper, he began his editorials with a Biblical quotation. This one comes from the Old Testament’s Song of Solomon.

“I am black, but comely, O ye daughters of Jerusalem, as the tents of Kedar. Look not upon me because I am black, because the sun hath looked upon me”.

This, like many of Plaatje’s writings indicated his strong Africanist commitment. By quoting Solomon – seemingly tongue in cheek – he hinted at the importance of a strong African identity in a world where racial discrimination was rife.

Koranta was critical of the British administration in the Transvaal and Orange River Colonies. Here, Africans continued to suffer at the hands of violent police and a judicial system that did not protect their human rights. Plaatje expanded the newspaper’s protest agenda gradually. He campaigned for the better treatment of Africans employed in urban areas and contended that the African franchise and civil rights of the Cape Colony should be extended to the rest of the country.

The Gods Must Be Cruel

Plaatje was a complex man. Although prefacing his editorials with Biblical quotes, at times he railed against what he saw as the Divine order of things:

“The gods are cruel, and one of their cruelest acts of omission was that of giving us no hint that in very much less than a quarter of a century all those hundreds of heads of cattle, and sheep and horses belonging to the family would vanish like a morning mist.

“They might have warned us that Englishmen would agree with Dutchmen to make it unlawful for black men to keep cows of their own. The gods could have prepared us gradually for shock.” – excerpt from Sol Plaatje’s Native Life in South Africa.

In later years, he withdrew from political organization and wrote the famous South African novel, Mhudi: An Epic of South African Life a Hundred Years Ago. His pen was his weapon in the fight for restoring the dignity to the African people. He continued this battle until his death in 1932.

He certainly lived up to his middle name Thekiso – adding advantage or gain. We continue to reap benefit from his contributions to journalism and the African literary landscape. — Zubeida Jaffer and Sibusiso Tshabalala

First published in thejournalist.org.za on 5 July, 2014

Nnamdi Azikiwe: African philosopher, scholar and eminent journalist

Like most African journalists who were propelled into the media space by the liberation struggles against colonisers, Dr Benjamin Nnamdi Azikiwe, also known as “Zik” was no exception. Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania and Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, were all activists before they became journalists and subsequently presidents of their countries. They were all leaders in the Pan-African Movement.

Nigerian first president and media pioneer Nnamdi Azikiwe.

(Courtesy: legit.ng/1162109-nigerian-heroes-contributions.html)

Nigerian first president and media pioneer Nnamdi Azikiwe.

(Courtesy: legit.ng/1162109-nigerian-heroes-contributions.html)

Azikiwe was born on November 16 1904 to Igbo parents in Zungeru, Northern Nigeria – the present-day Niger State. He is revered as the towering African pragmatic and progressive philosopher, scholar and eminent journalist of the 20th century. He was a scholar who wrote many works of educational philosophy. He attended various mission schools in Onitsha, Calabar and Lagos.

Life influences

Azikiwe briefly lived with a relative while attending school in Onitsha while holding down a job as a student teacher supporting his mother financially.

He would later join his father in Calabar in 1920, where he attended the Waddell Training College. It is here that he was introduced to the teachings of African-American civil activist Marcus Garvey. Garveyism, would become his philosophical compass towards nationalistic politics.

When he transferred to the Methodist Boys High School in Lagos his opportunities and access to influential scholars opened up. He was fortunate to attend a lecture by James Aggrey, an educator who believed that Africans should receive a college education abroad and return home to effect change on the continent.

Aggrey gave the young Azikiwe a list of schools that were accepting black students in America. Zik arrived in the United States in 1925, where he earned multiple qualifications, including Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees from Lincoln University in Pennsylvania and a second Master’s degree from the University in Pennsylvania.

At Columbia University, his doctoral research focused on Liberia in world politics. During his time in America, he was a columnist for the Baltimore Afro-American, Philadelphia Tribune and the Associated Negro Press. By the time he returned in Nigeria in 1934, Azikiwe’s ideals were traceable to the African-American press, Garveyism and pan-Africanism. He was a man on a mission once he realised how media can influence people’s psyche.

Activism and newspaper days

He applied for a position with the foreign services for Liberia but was rejected because he was not a native of the country, so he continued with his vision of a united Africa and returned to Lagos in Nigeria in 1934.

He accepted a job offer from Ghanaian businessman Alfred Ocansey to become founding editor of the African Morning Post, a new daily newspaper on the Gold Coast, now known as Ghana. The publication quickly became an important organ of nationalist propaganda pushing the Pan-Africanist philosophy.

He would mentor Kwame Nkrumah, who would later become the first president of Ghana, before returning to Lagos, Nigeria in 1937. There he founded the media outfit the Zik Group, under which he established and edited the West African Pilot, which was referred to as “a fire-eating and aggressive nationalist paper of the highest order”.

Under the Zik Group, he revolutionised the West African newspaper industry, demonstrating that English-language journalism could be successful, and expanded his controlling interest to more than 12 daily, African-run newspapers. The West African Pilot grew exponentially from an initial run of 6 000 copies daily, to printing more 20 000 copies at its peak in 1950. There was also the Southern Nigeria Defender in Warri (now known as Ibadan), the Eastern Guardian (founded in 1940 and published in Port Harcourt), and the Nigerian Spokesman in Onitsha.

In 1944, the group acquired Duse Mohamed’s Daily Comet. By 1950, the five leading African-run newspapers in the Eastern Region (including the Nigerian Daily Times) were outsold by the West African Pilot.

Azikiwe’s newspaper venture was a business and political tool. He even began writing a column – Inside Stuff – in the African Morning Post, in which he occasionally attempted to raise political consciousness. His collection of newspapers played a crucial role in stimulating Nigerian nationalism.

By the 1960s, after Nigeria’s independence, the national West African Pilot was particularly influential in the east. Azikiwe took particular aim at political groups which advocated exclusion. He was criticised by a Yoruba faction for using his newspaper to suppress opposition to his views.

To support his business ventures and to express his economic nationalism, Azikiwe founded the African Continental Bank in 1944 and also ran the Penny Restaurant.

Political life

He also became directly involved in politics, first with the Nigerian Youth Movement in 1944 and later when he led a 1945 general strike. On July 8 1945, the Nigerian government banned his newspapers, the West African Pilot and the Daily Comet for allegedly misrepresenting information about a general strike.

He founded the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons, a group which became increasingly identified with the Igbo people of southern Nigeria. And in 1948, with the backing of the National Council, Azikiwe was elected to the Nigerian Legislative Council, later serving as premier of the Eastern region from 1954 to 1959.

Zik would become the country’s first president when Nigeria became a Republic, governing from 1963 to 1966. Prior to becoming president he had been governor-general of Nigeria from 1960 to 1963. He was overthrown in a military coup on January 15 1966. He became a spokesperson for Biafra and advised its leader, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, during the Biafran War between 1967 and 1970.

After the war, he became the chancellor of the University of Lagos from 1972 to 1976. He would join the Nigerian People’s Party two years later, making unsuccessful bids for the presidency again in 1979 and 1983. He left politics involuntarily after the December 31 1983 military coup. Azikiwe died on May 11 1996 at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital in Enugu after a long illness.

He is buried in Onitsha. — Phindile Xaba

First published in thejournalist.org.za on 26 November, 2019.

Hilary Teague (1802-1853): Father of Liberia’s independence

Hilary Teague is being celebrated in contemporary times as the Father of Liberia’s independence and the foremost pioneer of the Liberian media. His legacy has also become an interest in scholarly works and literature, aptly so.

According to Dr Patrick Burrowes, a renowned Liberian historian, Teague’s legacy may have been tampered with simply because his last name is sometimes spelt differently, as “Teage”. But he contends that attempts to hide his unwavering commitment to the liberation of black people could not stay buried eternally.

Masthead of Liberia Herald which was edited by media trailblazer Hilary Teage.(Sourced: Facebook page on Hilary-Teage-Father-of-Liberias-Independence)

Masthead of Liberia Herald which was edited by media trailblazer Hilary Teage.(Sourced: Facebook page on Hilary-Teage-Father-of-Liberias-Independence)

Burrowes in an interview with the Liberian Observer said: “Teague was the father of Liberia’s independence. Just as Ghanaians uphold Kwame Nkrumah and the Americans look up to George Washington, Liberians need to honour the man who laid our foundation.”

Apart from writing numerous papers on his legacy, Burrowes staged a play chronicling Teague’s historical contributions to commemorate Liberia’s independence in July 2018.

Early childhood

It’s no wonder that Teague was so invested in Liberia’s independence as he was born to former slaves Colin and Frances Teague in 1805, in Virginia in the United States. His father, Colin and a friend Lott Cary had been ministers at the Providence Baptist Church they had established on a piece of land they purchased in Richmond. They emigrated with their families to a colony that was yet to be named by the American Colonisation Society (ACS), in West Africa as missionaries. Teague was only 14 then and for several years the family primarily lived in Sierra Leone, where Hilary and his sibling Colinette received elementary education for three years.

When they eventually moved to settle in Liberia, they then discovered that the history of the colony had been of no less than a huge dispute and discord between the settlers, a group the Teagues fell into and the ACS. Several rebellions had reportedly occurred regularly with no results. Teague, who was in his late teens when he set foot on the colony, is described by Burrowes as an inspirational person young people can learn from as he had minimal education but did not let that deter his determination.

He went on to become a successful businessman with some or full equity in different ventures. He even owned several ships, followed in his father’s footsteps and became a minister of three churches over time. Teague is said to have been bothered by the state of the lives of African people in their land, and had to do something to fight for independence.

Media and Writing

According to Marie Tyler-McGraw, Teague was widely viewed as a very bright man, but somewhat angry, an emotion that showed through his writing during his editorship at the Liberia Herald (1835-1849), which he also owned.

Teague unapologetically used this platform to champion the cause for Liberia’s independence, invoking black nationalism and religious heritage. Tyler-McGraw suggests that his writings demonstrate that his anger was fuelled by the exclusion of blacks from citizenship and opportunities viewed through his own experience in Virginia.

In one editorial he wrote: “New Virginia [a new settlement] is looking up. We trust we love all mankind … but somehow, we do love Virginia and Virginians. How strange that we should love a place that despises us and casts us out. Well, let New Virginia copy all in the old that is good and reject the bad.”

His editorials covered wide topics ranging from native plant and animal life, daily life and practices among indigenous groups, agriculture, and women’s fashions in Monrovia. His greatest interest was Liberian history and politics and he realised early on that Liberia must be independent. In a private letter, he assessed the relations between Liberia, the ACS, and the United States government accurately:

“You are probably aware of the nature of our relations with the people of the United States. With them as a nation we have nothing to do. From the first the Government disowned us, and up to this hour disclaims all political connection. With a few American citizens confederated under the title of the American Colonisation Society (ACS), we hold a temporary and conditional relation”.

Politics of liberation

In 1835, Teague became the secretary for the Liberian colony and progressed to occupy the position of a clerk of the convention which presented the settlers’ views of the ACS regarding constitutional reforms in 1839.

He was later an instrumental figure at the Constitutional Convention of 1847 – representing Montserrado County – in both debating and ratifying Liberia’s constitution, and wrote the country’s Declaration of Independence. In 1853, although Teague was the country’s first Secretary of State after Liberia declared independence, he served as attorney general as well. All his life he fought for secular political freedom far from his religious affiliation.

While Teague is said to have been a failure in all aspects of life in some quarters, Burrowes noted that Liberia should be weary of suppression of accurate African history by those who may desire to impose their distorted opinions.

“My greatest wish is that this play will unify Liberians and teach us to love and respect ourselves. A key to success in life is to know yourself but sadly, many of today’s Liberians look down on our ancestors because we don’t know our history,” Burrowes said.

Teague died in May 1853 aged 51. — Thapelo Mokoatsi

First published in thejournalist.org.za on 26 February, 2019.

Pioneers: Swazi Queen Labotsibeni

Queen Labotsibeni Mdluli was born in 1858 at eLuhlekweni northern Swaziland (now known as Eswatini) during the reign of King Mswati II who was in power for 25 years between 1840 and 1865. As fate would have it, she would rule the young Swaziland kingdom for 50 years.

Labotsibeni’s ascension to the throne was rather unusual. Firstly, Swati traditional laws did not allow a woman in her situation to rule; she had four children at that time. Secondly, her Mdluli clan was not next in line to rule Swaziland. But she defied the odds.

SeSwatini Queen Regent Labotsibeni (Gwamile) Mdluli.(Courtesy: Sarah Richards facebook page and www.sarahrichards.co.za)

SeSwatini Queen Regent Labotsibeni (Gwamile) Mdluli.(Courtesy: Sarah Richards facebook page and www.sarahrichards.co.za)

The daughter of Matsanjana Mdluli, whose brother was Chief Mvelase Mdluli, she was entrusted with bringing peace and stability in the wake of the political and social confusion the country faced. She was chosen because of “her outstanding intelligence, ability and character and experience”. This was groundbreaking for someone with no “formal education, her wisdom, her perception, her wit, and determination…”, states Thoko Ginindza, in her article titled Labotsibeni/Gwamile Mdluli: The Power Behind the Swazi Throne, 1875-1925.

This lioness, whose second name Gwamile means the indomitable one, first took the reigns as the Queen Mother for nine years between 1890 and 1899 and later served her people as the Queen Regent for more than two decades, between 1899 and 1921. It was during this time that she became involved in the affairs of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC), later renamed the African National Congress. She founded and financed its communications organ, Abantu-Batho newspaper in 1912.

Her role in Abantu-Batho newspaper

Grant Christison, notes in his PhD thesis African Jerusalem: The Vision of Robert Grendon that Mweli-Skota, that the Swazi Queen-Regent Labotsibeni “was the founder of the Abantu-Batho …[it] was formed in 1912 on [her] … instruction, and under the direction of Dr. P ka I. Seme …”

In March 1914, in Tsala ea Batho, Sol Plaatje observed that Abantu-Batho was privileged to have a black financier because it had six sub-editors, unlike other black-owned newspapers. Abantu-Batho came to be known as a publication that would raise the voice of the silenced African population in South Africa, a republic in which the oppressive regime was institutionalising landlessness, poverty in African people and oppression. Those were the pressing issues that gave the Queen-Regent many sleepless nights. Following Pixley ka Seme’s persuasive voice, Labotsibeni invested £3 000, a huge amount of money at the time.

“She remained in 1912 one of the wealthiest black women in South Africa,” notes Christison.

She offered the much-needed financial muscle to support SANNC activities. She was also a very astute entrepreneur who treated this exercise as a business decision to partner with Seme and company, thus making her a shareholder and Seme a managing director of Abantu-Batho – a limited liability company. As an oralate stateswoman she understood the power of the printed word and ensured that Abantu-Batho staff members reported on bread and butter issues happening in Swaziland and other parts of southern Africa for the world to learn about beyond continental boundaries.

During the First World War, Queen Labotsibeni purchased an aircraft worth £1 000 for Britain in support of its war efforts. She insisted that the aircraft should carry her name in order to reflect and acknowledge the role played by women in the First World War.

The April 25 1918 issue of Abantu-Batho sang her praises in commending “Ndhlovukazi and the people of Swaziland for the loyalty and devotion to the British Crown”, according to Sarah Mkhonza’s book Queen Labotsibeni and Abantu-Batho.

When she passed on in 1925 there was a heavy rain that led to flood in some parts of South Africa and Swaziland. She was a rainmaker reputed to have said: “When I want water, I make the rain myself.” — Thapelo Mokoatsi

First published in thejournalist.org.za on 21 February, 2017.