13th December 1963: Kenyan Prime Minister Jomo Kenyatta (c 1889 - 1978) and the Duke of Edinburgh drive through cheering crowds in Nairobi during the Independence celebration (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

I recently came across a Newsnight archive feature on the 1980 Rhodesian (now Zimbabwe) elections, which showed the hopefulness of newly independent Africans — optimistic of the future and Robert Mugabe’s potential. Many white Rhodesians were, however, visibly angry and scared.

At the close of the report, the anchor offers consolation: “Remember Jomo Kenyatta, who was loathed and feared by Kenya’s whites as the Mau Mau leader and became the father of one of Africa’s most harmonious multiracial societies.”

Yet Kenyatta’s rule was plagued with corruption, political assassinations and violence committed against his own citizens. How did he become both a darling of the West and a hero of Afrocentric scholars?

Jomo Kenyatta’s life is a study in political astuteness, incredible luck and demagoguery. From the outset, young Kenyatta seemed to possess a wily political awareness. While working at an early age as a carpenter’s apprentice, store clerk and water meter reader, the future president changed his name from Johnstone Kamau to Johnstone Kenyatta.

The name also works as a play on the words Kenya and taa (light), meaning “light of Kenya” — no coincidence. When he later moved to London, he would assume “Jomo” in the place of Johnstone, reincarnating himself as Jomo Kenyatta, the African independence leader.

He realised how powerful-sounding Africanised names would be beneficial in his political career, decades ahead of African leaders like Zaire’s Mobutu (full name Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu waza Banga,) who would ride the wave of bombastic-sounding name changes in the late 1970s. His natural ability to manage his public image was key to the way he is remembered today.

After taking over the reins at the Kikuyu Central Association in 1927, Kenyatta would then travel to the United Kingdom, where he fell in with a communist crowd. After a short break studying in Russia, he moved back to London, gaining degrees at the University of Central London and the London School of Economics, where he published his celebrated (if nostalgic) thesis on the Agikuyu culture, Facing Mount Kenya.

Returning to Kenya in the early 1930s, he found a country where politics had moved forward, and the Kikuyu were even more agitated about land issues. A political chameleon, his communist association and experience as leader of the long-standing colonial agitator, the Kikuyu Central Association, would win him support of the radicals. At the same time, his social “finesse” and academic credentials could woo the constitutional (democrat) factions.

Advancing in age, he utilised African respect for the elders to place himself as the sole leader of the independence movement. This grew to the extent that when he was arrested by colonial authorities, “no uhuru (freedom) without Kenyatta” was the clarion call across the board.

Yet, it’s only after independence that the real Kenyatta emerges.

As leader of the Kenya African National Union, he won the 1963 election and took up the position of prime minister. Under his lead, Kenya moved from a colony to a republic.

The country’s first president must have learned something in his Western sojourn. He came back with a big appetite for land. His family, friends and other hangers-on engaged in rapacious grabbing of lands then owned by the departing British settlers. The practices of the former oppressors seemed to come easily.

Kenyatta also presided as the disappearances and deaths of politicians began to take place: first was Pio Gama Pinto and then, famously, Tom Mboya and JM Kariuki. This coincided with an increasing dissent within the ruling National Union Party.

He also abused traditional systems to ensure fealty.

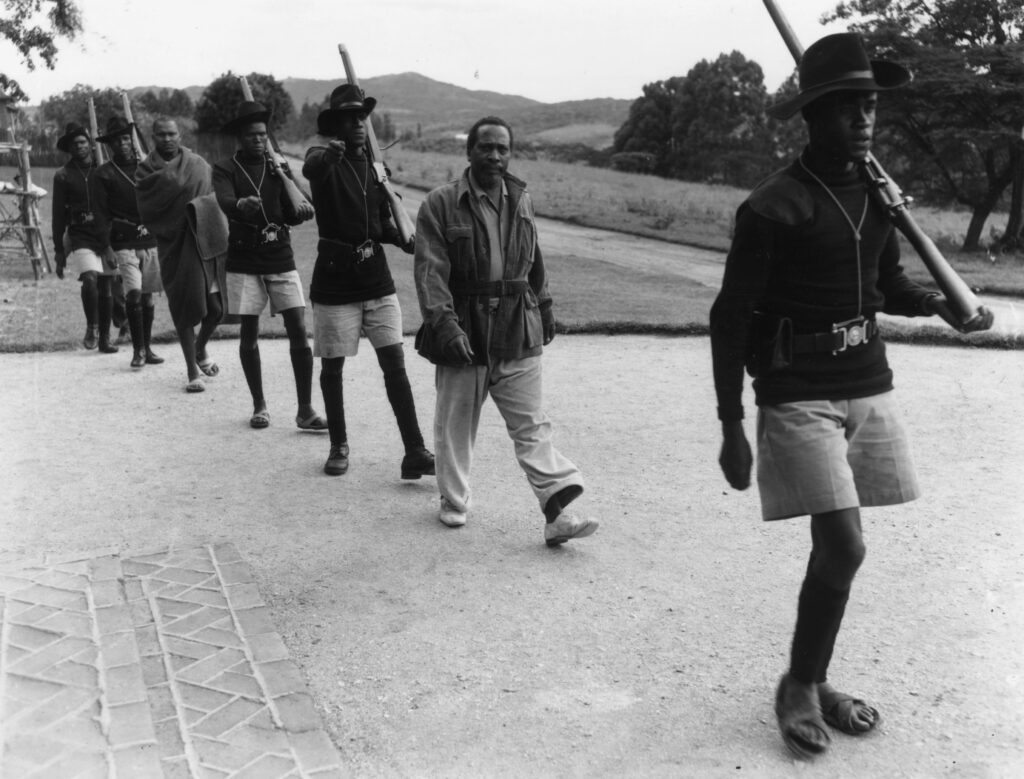

19th November 1952: Future Kenyan president Jomo Kenyatta (c.1891 – 1978) being led into a courthouse in Kenya, charged with leading the Mau Mau Rebellion against the British. (Photo by Stroud/Express/Getty Images)

19th November 1952: Future Kenyan president Jomo Kenyatta (c.1891 – 1978) being led into a courthouse in Kenya, charged with leading the Mau Mau Rebellion against the British. (Photo by Stroud/Express/Getty Images)

With freedom won, Kenyatta’s government had to tackle the Mau Mau freedom fighters, who had fought the British and now came back to a life without jobs or land. For them the only tenable difference was that the overlords had changed; it was no longer the British lording over the country’s wealth, but the nouveau riche.

So, as the promise of land redistribution faded away, the president drew on the famed oathing of warriors. This tribe-wide oath (sometimes forced) saw people swearing to always support him as their leader.

Beyond Kenya’s Central Province, Kenyatta did not hesitate to use violence to quash any rumblings of discontent. Most notable was the five-year-long Shifta War against Kenyan Somalis that resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands.

Outside of the country’s borders, and as colonialism fell, Kenyatta sang the tune of “African solidarity” without ever rocking the boat on the international stage.

He was also one of the few African leaders to continue relations with apartheid South Africa. An early ally of Israel, unlike then-African governments, he even provided Kenyan airports and airspace for the 1970s Israeli raid on Entebbe in neighbouring Uganda.

Yet, there were no sanctions for Kenyatta, no gruesome Hollywood epics detailing the rollercoaster ride that took him from shamba-boy to a London socialite; rebellion in the forests to Benz-driving fatcat; to paranoid megalomaniac, ally to apartheid and finally ruthless oppressor.

Instead, he is remembered as a pan-Africanist leader. Why?

This requires much deeper research.

It may very well have to do with his constant shedding of his skin. Thanks to his knack of being able to read the signs and reinvent himself, he saved himself from the fate of numerous independence leaders who were killed or overthrown in later years, dying in office of a heart attack.

Kenya was, and remains, a vital ally and “anchor state” to the West; these foundations were laid by Kenyatta, and perhaps as a token of thanks, he has been spared the indignity of exposure by Western popular culture in a way that former Ugandan dictator Idi Amin was not.