A foreign migrant sits on his bed inside a boarded up room occupied by two people on the upstairs floor in a building in the Kwa Mai Mai area in Johannesburg, on May 14, 2020. - Over 50 people, residents of the same building and mostly foreign nationals are currently unemployed because of the lockdown imposed by the South African authorities to curb the spread of the COVID-19 coronavirus. Dozens of them are unable to feed themselves, as the only charity providing them with food has not brought any in several days. (Photo by MARCO LONGARI / AFP)

In 1994, 16 June was declared Youth Day in South Africa in remembrance of those who died and suffered during the student uprising of 1976. This year marks its 46th anniversary.

In 1976, pupils marched in protest against the poor quality of education they received under the Bantu education system and demanded to be taught in their own languages. Racial injustice was so extensive that — despite the uprising — by 1982 the apartheid government spent an average of R1 211 on education for each white child and only R146 for each black child, an eight-fold differential.

This year, the government’s theme for Youth Month 2022 is “Promoting sustainable livelihoods and resilience of young people for a better tomorrow”. The campaign not only highlights difficulties faced by the youth but also presents possible solutions through dialogues, as well as showing opportunities available for the youth.

With 200 million people aged 15 to 24, Africa has the largest population of young people in the world. The continent also has the fastest growing youth population in the world, with 60% of its population under the age of 25. It is the only region in the world where the youth population is increasing.

A recent report forecasts that by 2050 sub-Saharan Africa’s young population (up to the age of 24) will increase by nearly 50%, compared with other regions in the world that have a projected decrease in youth population with -41% in South Asia and -6% in Western Europe and North America.

Although Africa’s youthful population holds development promise, recent youth unemployment statistics are cause for concern. There is no unique determinant of the youth employment problem in the African region but the pool of factors contributing to rising unemployment among the youth creates political disputes in the region. In sub-Saharan Africa the majority of potentially employable active youth regularly suffer from under-employment and poor decent working conditions if they can find work.

In today’s labour market, the transition from school to work is particularly difficult globally. According to the International Labour Organisation, prior to the Covid-19 pandemic younger people were about three times more likely to be unemployed than adults. The economic crisis induced by governance responses to Covid-19, combined with the unprovoked Russian war with Ukraine, now threaten to exacerbate the levels of unemployment already endemic to sub-Saharan Africa.

According to a United Nations special report on youth and employment, young people account for 60% of all of Africa’s jobless population. In North Africa, the youth unemployment rate is 25% but is far greater in Southern Africa, with 51% of young women and 43% of young men being unemployed.

The youth unemployment rate in South Africa was 59.6% in 2020, the highest of any G20 country, followed by Brazil with about 30.5%. In contrast, Japan’s youth unemployment rate was the lowest in the world at roughly 4.5%.

According to South Africa’s Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) for the first quarter of 2022, the unemployment rate was 63.9% for those aged 15 to 24 and 42.1% for those aged 25 to 34 years. Although the graduate unemployment rate remains relatively low in South Africa compared with those of other educational levels, unemployment among the youth continues to be a burden, irrespective of educational attainment. The unemployment rate among young graduates (15 to 24 years) declined from 40.3% to 32.6% while it increased from 15.5% to 22.4% for those aged 25 to 34 (from QLFS 2020 to QLFS 2021 respectively).

Of the 40 million people in the working age population in the first quarter of 2022, more than half (51.6%) were youth (15 to 34 years). The employed youth is contributing significantly to driving the South African economy and those who seek development and employment should be empowered to realise their fullest potential.

Employment is a key economic and social indicator. The size and unemployment trend in the youth population has negative implications for any country’s development trajectory. Although a relatively large number of people of active working age can be a demographic asset, the potential economic benefit can only be realised if they are healthy, well-educated, have access to a dynamic economic environment and a stable, predictable political environment. One of the prime requirements for African youth is labour-absorptive growth.

Education remains the primary channel through which to train up employable young people. The education sector in Africa is going through trying times as it attempts to recover from the Covid-19 lockdowns. Some scholars had access to online learning but those in remote and rural areas had little to none, which has had a negative bearing on the completion and pass rates respectively.

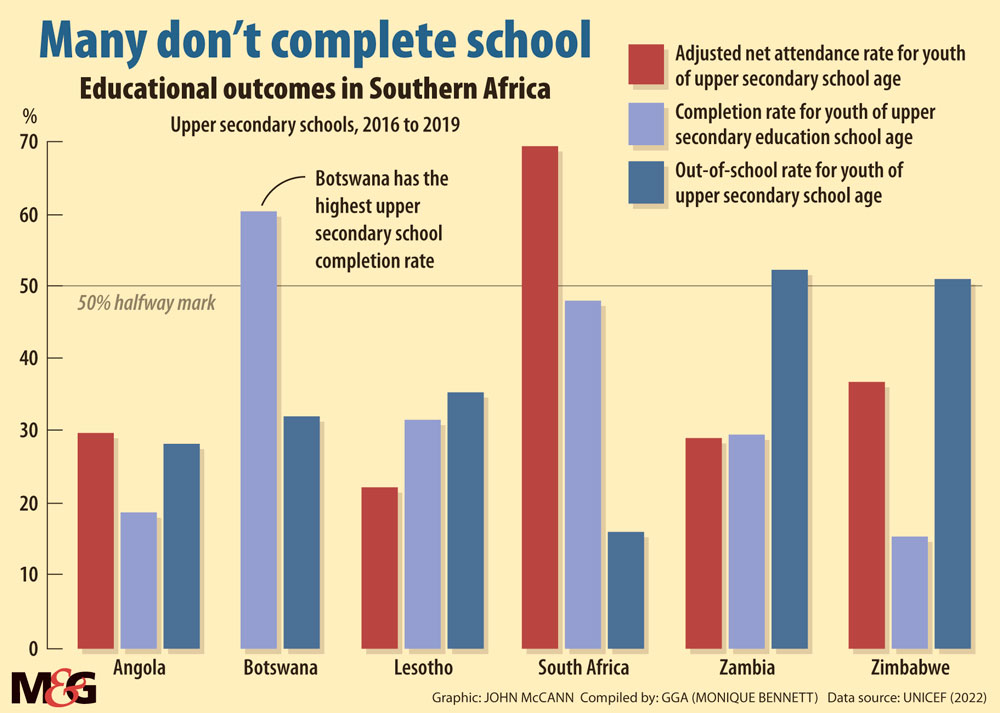

Even prior to the lockdowns, educational success metrics were not positive for sub-Saharan Africa. According to the World Bank, the lower secondary completion rate fwas 43.7% in 2019 compared with the global rate of 70%. The United Nations Children’s Fund’s education statistics indicate that Botswana had the highest completion rate for upper secondary education (60%) and Zimbabwe the lowest (15%). The graph provides a telling snapshot of educational outcomes in Southern Africa.

Education remains the key to the young people’s prospects of economic improvement on the continent. The solution is not necessarily to channel more funds into education but rather to ensure that the education system is fit for purpose and that resources are allocated more proficiently.

There is therefore a strong case for the government and private sector to channel more effort into ensuring that young people have the technical and intellectual skills that can equip and empower the youth to not only be employable but to also create employment.

Christine Dube is head of the governance insights and analytics programme at Good Governance Africa.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.