On May 10 James Kilgore, the former Symbionese Liberation Army fighter who was finally arrested in Cape Town as “John Pape” in 2002, marks his first year out of prison. The man who evaded arrest for 27 years tells Gavin Evans about his life on the run, his remorse and his unshakable links to South Africa

Faces of a fugitive: Old photos of James Kilgore that were displayed at a press conference announcing his arrest in 2002. (Photo: Jakub Mosur/AP) James Kilgore has completed his first year as a free-ish man after six-and-a-half years in jail and 27 on the run. He wears a parole ankle bracelet, and until now has been barred from leaving the state of Illinois, but he certainly seems at ease in small-town Champaign — a happily married 62-year-old, with two grown-up sons and a new career as a budding author.

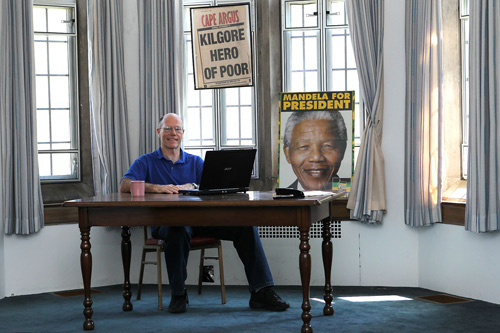

For those who knew him as “John Pape” during his decades as a fugitive, the almost rural surroundings — wooden decking leading on to a leafy garden where squirrels and rabbits frolic — might seem out of place. But it soon becomes clear that the links to that past remain steadfast. The first thing you see on entering his study is a “Mandela for President” poster and a framed poster from the Cape Argus of November 11 2002, saying: “Kilgore: Hero of Poor”.

Soon after that poster appeared on the streets of Cape Town, US federal marshals escorted a handcuffed Kilgore on to a flight to New York, to face trial for his violent activities with the California-based Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA). Kilgore, the last of five SLA members to be tried. He was sentenced to six years in a state prison for his part in the killing of Myrna Opsahl, a 42-year-old mother of four, in a bank robbery in 1975.

He was also tried and sentenced to 54 months in federal prison on explosives and passport fraud convictions. Kilgore pleaded guilty as charged.

His Southern African life as an educator and activist, father and husband was over. His future lay behind bars in the maximum security prisons of the United States.

And yet those links have remained strong. His study wall also features several pinboards packed with pictures and postcards he received from friends while in prison. Every November 8, the date of his arrest, they would hold a party to celebrate another year closer to release.

“The title changed each year,” he says, relishing the memory. “One-down, two-down, until it got to six-down. I loved getting the pictures.” He pauses to point at some of them. “Their support helped me survive. They helped me stay sane enough to write.”

A cuffed Kilgore arrives at court in Cape Town

(Photo: Obed Zilwa/AP) Writing has been Kilgore’s prime focus over the past year. The novel he completed in prison, We Are All Zimbabweans Now, was published to enthusiastic reviews shortly after his release and was recently chosen by the Berlin Film Festival as one of the 10 “most appropriate books for film adaptation”. He wrote a screenplay based on the novel, has since completed a trilogy of crime novels with links to Southern Africa and is finishing another set in post-1994 South Africa, while starting yet another, about an American activist from the 1960s.

He is also advising a prisoner education project, learning sign language, working part-time for a union, delivering lectures on Africa and keeping fit through cycling.

It’s an eclectically busy schedule that, in a way, has been a feature of his life. In his school days, this California businessman’s son seemed to shine at everything he tried, although he downplays this suggestion. “I was on the basketball team but by no means a star; I was on the golf team but not a scratch golfer and a good student but not top of my class. I was a sports fanatic who didn’t read books.”

This passion continued at university until he faced the prospect of being drafted for war. “In less than a year I went from being an athlete to somebody who read books and went on demonstrations,” he recalls. “It forced me to reflect on the nature of the Vietnam War. Plus, there was lots of activity at UC Santa Barbara in 1969-70 that culminated in the burning of their Bank of America branch.” He raises a finger: “In which I didn’t participate! We ended up with a state of emergency with troops and armoured personnel carriers.”

But it all turned sour in the 1970s. “The anti-war movement got diffused when they got rid of the draft, and the people involved were at sea about what to do next. There was also repression and destructive sectarianism.”

One group that emerged from this fetid atmosphere was the SLA, which made its name by kidnapping the 19-year-old heiress Patty Hearst, who went on to become the gun-wielding “Comrade Tania”. Soon after, six founder members were gunned down by the police and the gap was filled by new recruits, including Kilgore’s girlfriend, Kathy Soliah, who persuaded him to join them.

He is restricted by court order from discussing SLA activities, but Hearst portrayed him as the “calm, reasonable, level-headed” member who specifically argued against using a favoured hair-trigger shotgun on their missions.

Kilgore now — at home, putting his past behind him. (Photo: Liz Brunson) Still, he was part of the group that robbed the Crocker National Bank in Sacramento, where another SLA member accidentally discharged that shotgun, killing Opsahl, a customer.

Five months on, following a failed attempt to bomb a police car, Hearst and five others were rounded up. Kilgore escaped and headed north, but a warrant was issued for his arrest after a pipe bomb was found in his apartment. He says he “almost immediately” regretted his role. “When I got to Seattle I could see everything we’d done had come to nothing positive. It’s a futile way of operating. We were not doing anything to empower anybody. You pretend you represent people but actually have no connection to them at all.”

But he was still a wanted man, so he followed “the old routine of getting the birth certificate of a child who died”. He explains: “At that time you could walk into a county registrar with $2 and say, ‘I’d like that birth certificate for that person’ and they handed you a copy, stamped it and you could get a passport.” And so he became Charles William “John” Pape, his name for the next 27 years (his wife, Terri, and most of his close friends still call him “John”).

The FBI suspected he was in Canada, but instead he moved to Minnesota where, despite his “wanted” status, he linked up with activists campaigning against apartheid and minority rule in the former Rhodesia.

Five years on he relocated to Zimbabwe, a country whose politics he captures in his novel. We Are All Zimbabweans Now is the tale of a US academic who lands in Zimbabwe full of admiration for Mugabe, only to find disillusionment setting in. But unlike his protagonist, Kilgore was sceptical. “I didn’t arrive with grand illusions. I didn’t see Mugabe as this monolithic hero. I didn’t have a high regard for him.”

He went on to complete a PhD, learned to speak Shona, taught at a polytechnic, a domestic workers’ school, and a township secondary school and married Terri Barnes, an American PhD student.

They moved to Johannesburg in 1991 and he began teaching at Khanya College, where he later became director, and then to Cape Town where he worked on education and research for trade unions, ran workshops and produced booklets on subjects such as globalisation. “This experience reiterated to me the difference between an organisation that genuinely represents people and the kinds of things I’d been involved in before in terms of small group violence,” he says.

He might have remained undetected had it not been for the arrest of Kathy Soliah (living in Minnesota as “soccer mom” Sara Jane Olson) — which prompted her to join three of her former SLA comrades in cutting a plea-bargained deal. Kilgore decided to follow suit and in April 2002 retained lawyers for this purpose.

“This involved secret calls to my lawyer in the States,” he explains. “I’d sneak off to find a payphone so I’d have a non-traceable line. I also went to fancy hotels and phoned from their desk, and I’d go to the UCT library and surf the internet to see if there were any leads to me from the Sara Jane Olson case. I don’t know who my lawyer spoke with as we were trying to be careful, but obviously the careful part didn’t quite work out.”

He’d been planning to hand himself in by January 2003, but received his first and only hint of trouble on November 7 2002 when two South Africans arrived for a “survey on the shape of wine bottles”. They held up two bottles and said: “Which one do you like better? Here, just touch it and feel it.” Kilgore held the bottles and realised: “These people are getting my finger prints — and they were.”

The next day he planned his final family holiday before driving his son home from cricket practice. As he arrived, two plainclothes cops emerged, one with his jacket open, showing a pistol. “They told me to put my hands on top of the car and show my ID so I threw it on top of the car,” he says. “A caravan of kombis and cars was driving toward us. Then the captain got out and asked if I was James Kilgore. I admitted my identity, then hugged and kissed my son and a woman officer put him in a car. They put me in the back seat of a four-wheel drive, but as we pulled away, Terri pulled up. By then, my hands were cuffed behind my back so I couldn’t even wave.”

He was fingerprinted and then returned home so that police could collect his identity papers. Terri handed him blankets, cookies and books (including Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom, which he read in the Bellville police cells).

Kilgore says he felt “totally relaxed and lucid”, but hesitates when asked whether he felt relief at no longer being on the run. “I suppose there was a certain relief,” he says before adding that his fugitive life had been “more ordinary than you’d expect”.

He was extradited to California, where he pleaded guilty in two hearings. He was sentenced to four-and-a-half years on federal charges relating to the pipe bomb and possession of an illegal passport, and to six years on a state charge of second-degree murder, relating to his part in the bank robbery.

In court, he apologised for his role in Opsahl’s death, but he stresses: “No matter how often someone says sorry, it doesn’t satisfy those who suffered, and also won’t satisfy the media people who want mea culpas in a hundred different forms. My 20 years working as a teacher provide stronger evidence that I am genuinely sorry, that I recognise that I took a wrong and destructive path. Actions speak louder than words.”

His years inside were divided between two Californian prisons – mainly high security with spells in “maximum custody”. His main job involved tutoring prisoners in maths and computer science. “I enjoyed that side of it,” he says. “There was a small core who were extremely dedicated and very receptive.”

Spare time was spent on his own projects, including his Zimbabwe novel. This involved tapping away on a manual Olivetti typewriter with an ancient ribbon (revived after he took an inmate’s advice of treating it with baby oil). He sent a draft to his 90-year-old mum, who loved it – but his literary friends were more critical, so after another handwritten draft (he lost access to the Olivetti), he sent it to his mother-in-law for typing.

Several edits followed before a friend submitted it to Umuzi (a Random House imprint), which snapped it up.

Meanwhile, his family remained in Cape Town, but travelled to the US several times to visit him, while also keeping contact through phone calls and letters. They returned to live in the US in 2008. “When my prisons weren’t on lockdown, I was able to phone twice a week for 15 minutes and it was wonderful to hear their voices.”

Pointing again at those pinboards, he says the main factor keeping him sane was his Southern African friends. “Their support helped me survive,” he says. “Obviously, there were a few disconnects in terms of personal relationships when I got out, but I wasn’t as isolated as some prisoners.”

And now, with spring in the air, a year of freedom under his belt, and a clutch of novels and screenplays in his quiver, the former John Pape seems to be flourishing once again. “Really,” he says, “things have gone pretty well.”

A great memory for detail

I first met “John Pape” in Johannesburg in 1991, but I have only a vague memory. Kilgore, however, has no trouble recalling the details. When I mentioned it at the start of our interview he reminded me of the date, venue, dinner guests and topics of conversation. It was no less than expected because by then I had come to appreciate his astonishing memory for detail.

Eleven years after that first meeting, I wrote a feature on his arrest for a British magazine. I was surprised to receive a letter from him a few months later, written from his California prison. After that, we corresponded periodically — discussing his work in prison, the progress of his novel and the crisis in Zimbabwe.

At the time I was surprised that someone locked up without access to the internet could be so precise and accurate about historical detail.

When his novel was published last year, I was again astonished by his memory. He seemed to revel in the visceral details and told me that to fill in the gaps he wrote a “sensory prison diary” and it was the smells, sounds and sites of Harare that came back most strongly.

“When I reflect back,” he says, “the period in Zimbabwe in the early 1980s is the one I remember most vividly. When I arrived, my senses were on high alert, and I also had the fortune of living with Zimbabweans who oriented me towards the culture and the language in a way very few expatriates experienced.”