The Africa Bonani 2010 exhibition and conference held at The Castle in Cape Town last month highlights how post-apartheid South Africa photography faces a slew of new challenges

Documentary photography suffers from a certain inbuilt obsession with the margins, the dispossessed and the spectacular. Often conveying images of suffering to audiences distant from the pain, subjects are frequently turned into objects.

And yet, if these images were not captured, our collective memories would be impoverished, restricted to middle-class everydayness.

At the conference organised by the South African History Online website, hundreds of participants debated the ethics, aesthetics and politics of representation. Photographers were asked to submit photographic essays depicting the realities — and fantasies — of the new South Africa.

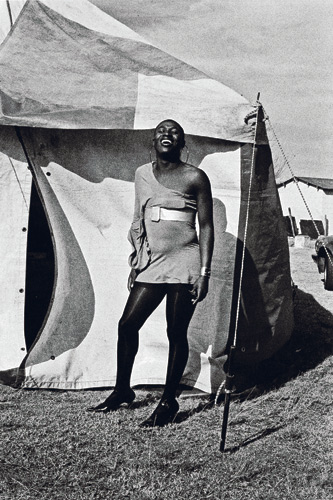

Ali, from Araminta de Clarmont’s Life After series

Fifty-six photographers responded, submitting 61 essays that audiences could view at the exhibition.

In his essay, In Defence of Social Documentary Photography, printed in the introduction to the Bonani catalogue, historian John Soske argues that the view that apartheid-era documentary photography was practised without a consciousness of the theoretical issues about representation, self reflection or aesthetic sensibility is a reductive interpretation of the works themselves.

This understanding is informed by a binary view of the aesthetic and the political, each regarded as discrete, mutually exclusive realms, and generating categories such as high art and social realism — the former a province of fine art, the latter a form of propaganda.

Rather, Soske argues, apartheid-era photographers conferred a reality on black life under a regime that conspired to render blacks invisible and to eradicate all traces of black existence from the national scene. These photographers, argues Soske, were challenging a visual regime, where the visible and the invisible were politically determined and where the aesthetic was overdetermined by a fascist political project.

Bigboy, from Sabelo Mlangeni’s Country Girls series

Today, documentary photography is faced with new challenges. “A post apartheid generation of photographers,” writes Soske, “has greatly enriched the visual idiom by experimenting with aesthetics and the medium itself to forefront questions of identity, sexuality, subjectivity and personae.”

Yet the persistence of apartheid structures, more visible than ever, “pose the basic question of social documentary with intensified force”.

While the three-day conference debated the issues concerning representation, the exhibition set out images that document post-apartheid, indeed postmodern, South Africa.

The essays were almost equally divided into those that continue the established tradition and those that present phenomena that are more recent and, if not new, at least newly acknowledged.

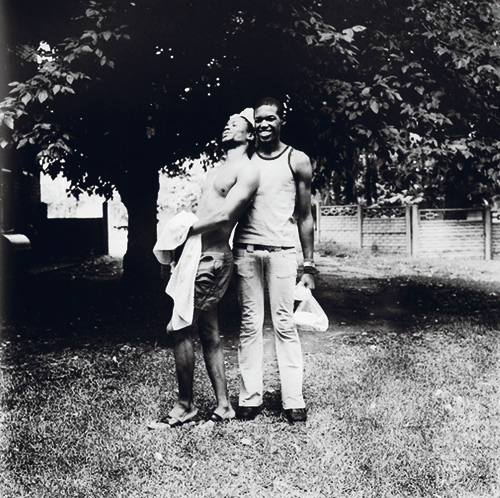

Sabelo Mlangeni recorded the quotidian activities of security guards and taxi drivers living in the George Goch hostel on the East Rand, harking back to earlier modes of documentary. He also celebrated the subculture of gay black men.

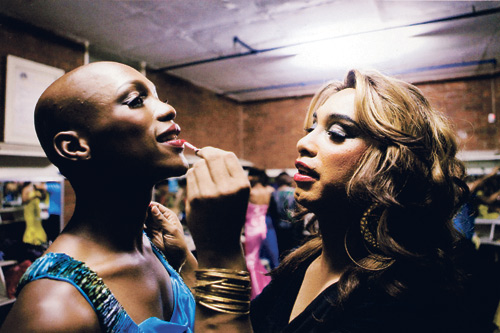

Damien Schumann’s essay continued the focus on marginalised sexuality, with colourful scenes from gay and transvestite beauty pageants.

Damien Schumman’s Beautiful series focuses on marginalised sexuality

Other contributions explore a range of subjects — tattooed prisoners who are members of Numbers gangs, tik smokers, street children, passengers waiting at terminals, white car guards, unemployed men at the side of the country’s roads, rubbish collectors, jazz musicians, churchgoers, pavement dwellers, refugee centres and service delivery protesters.

Gabeba Baderoon, speaking at the conference, encapsulated this cacophony: “What we choose to display in our public spaces, who curates our perspectives, who becomes visible to us in art represents a national conversation [about] who ‘we’ are.”

Three winners were chosen — Santu Mofokeng, Chris Ledochowski and the Mail & Guardian‘s Oupa Nkosi.

Ledochowski’s relationship with his subject, Petros Mulaudzi, demonstrates the difficulties of this fraught entanglement. Mulaudzi was a domestic worker at the home of the photographer. Ledochowski’s visits to Mulaudzi’s home in Nthabalala, Limpopo, took place over a period of 30 years. One can only speculate about their relationship, which must have transgressed the norms of baasskap.

Ledochowski’s portrait of Mulaudzi in his storeroom is, like many of his photos, in black and white. Mulaudzi stands slightly off-centre, staring off to his right, deep in thought. Around him the relics of his life populate the storeroom, hanging from rafters and stacked on stools and tables. Mulaudzi is almost scrawny, his body lean, but not unhealthy.

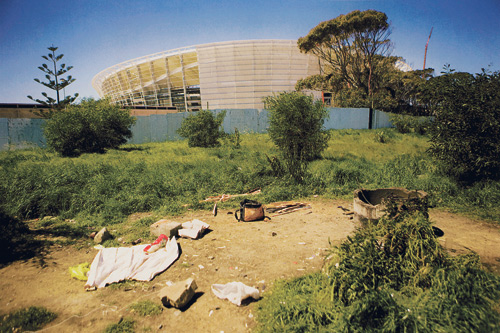

Outside Cape Town Stadium is from Samantha Reinders’s In the Shadow of a Stadium series

His face is marked by age. Intimacy pervades the image. But it is not all politics, even when it tries to be. Mawanda Isaac Mbongela’s image of a shack in Mahaleng struck me as a painterly composition, the majority of the surface taken up by yellow-green grass in the foreground, while a grey, cloudy sky appears to be the result of brush-strokes.

The mkhukhu (shack) at the centre stands on a piece of ground marked out by a fence, the lines of the poles standing vertically at intervals around the property.

The aesthetic rendering of this most basic of dwellings makes the scene pleasing to the eye, despite the fact that Mbongela wants to portray the lives of informal settlers denuded of services such as electricity or piped water.

Others are more self-consciously in search of the comic and the strange.

Kutlwano Moagi’s black-and-white images of Jo’burg buildings reveal his eye for the unreal among realist settings. His 777 on Bree Street is a collage of layered images: a fading shop-front window with a joker perched over a numbered square, burglar bars behind the broken glass and shadows darkening the window.

Kgomotso and his Boyfriend from Sabelo Mlangeni’s Country Girls series.

The play of light, dark and shadow point at the decrepitude of the inner city, but the cartoonish presence of the joker makes the overall atmosphere more intriguing than a simple lament.

Lenore Cairncross’s experiments with images refracted through a watery medium are beautiful, resembling surrealist paintings. Ostensibly an exploration of slavery and its relation to water, over which slaves were transported to various destinations, the aesthetic effect of her images seems to work against her political intent, as the images have little representational efficacy.

Underlining the disjuncture between the old and the new, Nkosi’s essay on the black diamonds is in stark contrast to the documentary traditions of yesteryear.

Black Diamonds , a series by Oupa Nkosi)

Now the black is diamond studded, adorned with designer-label clothing, sipping whisky in Sandton.

These full-colour images chart the rise of a vibrant new class, taking to the golf course in a world where all doors are open. Apparently.

Photography lends itself to ambiguity and the thoughts that images inspire are bound by no agenda; a free play of thought and apprehension.

Mofokeng’s images, inspired by a concern for global climate change, are beautiful and intriguing, evoking a kind of aesthetic mysticism inspiring a love for the Earth.

Omar Badsha, the chief executive of South African History Online, has decided to make the festival a biannual event, extended to include photographers from the whole continent.

The entire exhibition can be viewed online. Click on the Bonani icon at SA History Online’s website, www. sahistory.org.za/pages/index/menu

Oupa Nkosi’s thoughts about the photos

Mail &Guardian photographer Oupa Nkosi was one of three winners in the Africa Bonani 2010 exhibition. He tells Duduzile Mathebula how he came up with the two series he submitted for the exhibition, Displacement and Black Diamonds.

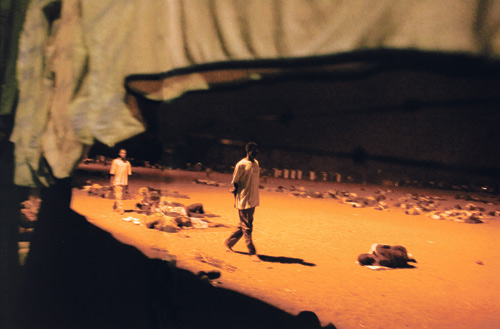

One of the photos in the Displacement series by Oupa Nkosi

“The pictures speak of wider issues than migration. These people came to South Africa for economic empowerment. Xenophobic attacks are just cold and unnecessary. ‘Why are we doing this?’ I ask myself. These people are our brothers and sisters. These people helped our leaders in the struggle and now we are treating them like our enemies. It just becomes black-on-black violence.

“These pictures speak a lot about the situation in our country. Where there is smoke there is fire. The influx of all these foreigners has put pressure on our government in terms of service delivery. People are competing for scarce resources. Our government needs to deal with the situation.

“We should strive to see things differently. These people are skilled and we should look at the positives. These people are able to be entrepreneurs and this is something we can learn as South Africans. They are business-minded. We can learn from them. This also could relieve dependency on government.

“The difficulty with this was capturing people in pain — especially as a person who disapproves of the xenophobic attacks. These people are still in pain and so many of them are still mourning the lives of their loved ones.

Something I know about black people is that they never give up. These people can survive anywhere. It is not about the adults only but the children too.

“This could also happen to us, and what would we do? It is not nice to see families dying and being torn apart. If we don’t receive help from the government, what are we going to do to fend for ourselves? Can we survive anywhere in the world?

“South Africa has poverty and this is usually covered. Black diamonds, for me, present a new aspect. After 1994, with democracy, I can see that black people are exposed to opportunities.

“Sometimes only particular individuals get these opportunities, but we are now able to get higher positions. This is how the project started, looking at opportunities for black people.

“People are working hard and acquiring wealth. They are being exposed to opportunities and not only glamour. I wanted to expose this to people — we are not only poverty stricken. With education wealth can be achieved.

|