Before the Marikana massacre

In Marikana, Lonmin's Newman shaft slopes down an incline to a depth of 396 metres. In June this year, I visited the shaft to learn about working conditions, descending to the seventh storey below ground, to see where the rock-drillers work.

To reach the lower levels, a miner has to jump on top of what resembles a metal bicycle seat, with handlebars and footrests, suspended from a cable system that disappears into the depths of the mine.

Two cables run down the incline – one brings workers up, the other takes them down. Once seated and gripping the metal handlebars, the miners descend, with about five metres separating each passenger.

There is an icy draft running through the shaft, and miners wear thick windbreakers, gumboots, overalls, and headgear to protect them against the elements. As we descend, tired and dirty workers pass us on their way up. Half-eaten biscuits and sweet wrappers litter the shaft's dusty concrete floor, a little less than a metre below our feet.

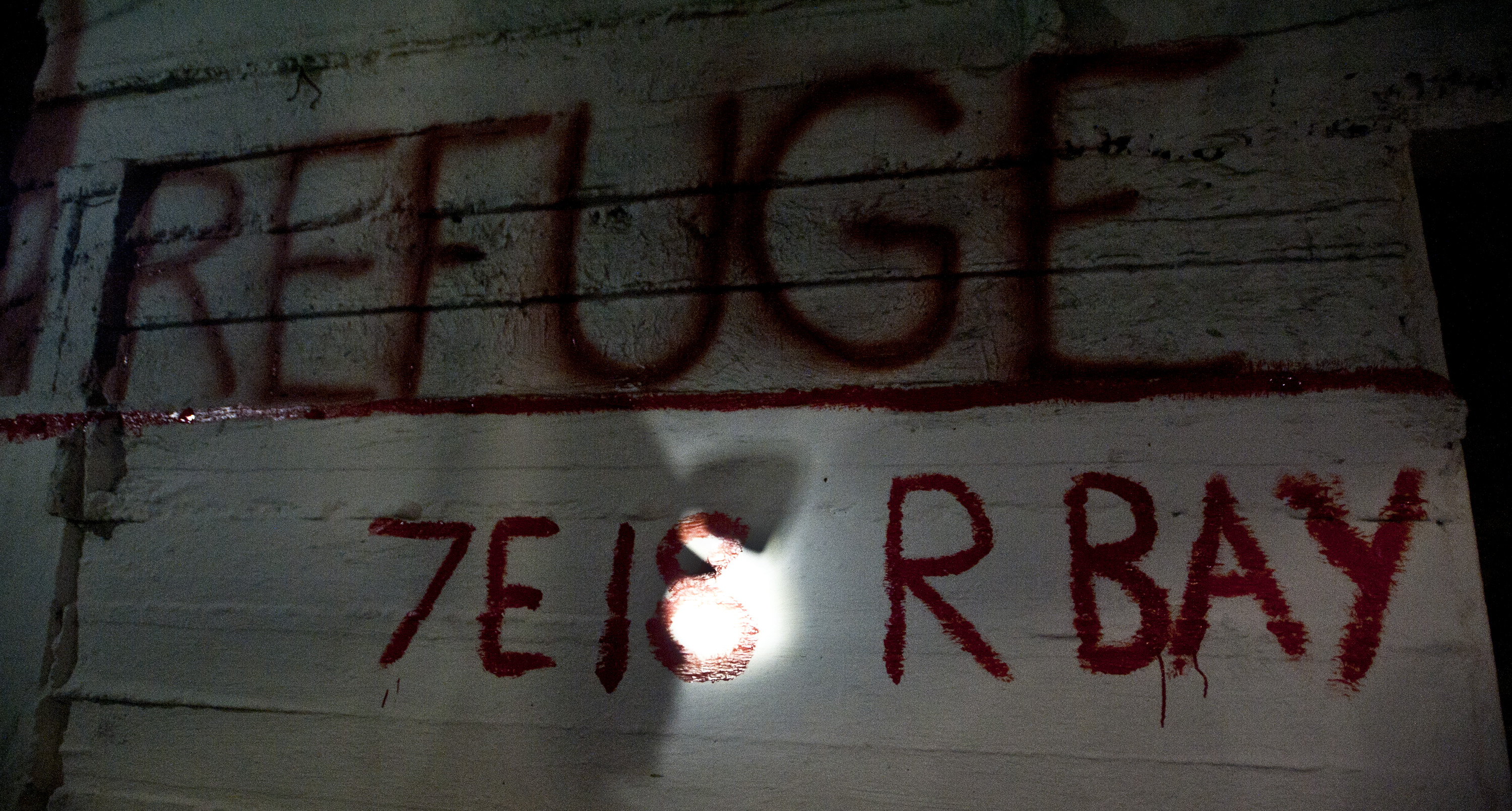

At each level, there is an even, concrete platform where miners can jump off. To the sides of the sloping tunnel, hallways stretch out on a horizontal plane. These have ceilings about five metres high, and a breath of similar length – concrete lined tunnels under the ground. The floor is wet in the dimly lit tunnel, with tracks for mine carts carrying ore running down the centre of the floor. Safety warnings and reminders pop up every few metres: "Safety first. Think and stay alive."

From these larger passages, smaller tunnels sprawl. This is where the rock drilling and blasting takes place. These tunnels are about 1.5m in height and pitch dark, save for the light from the headlamps on the hard hats of the rock drillers.

There are about eight men in the team I visit. The men have to either crouch or sit. It is hot – temperatures here can reach as high as 45°C and workers are at risk of heat stroke – the windbreakers are gone, and the overall tops are peeled off, revealing sleeveless vests. The tunnel floor is wet from water that is sprayed onto the drill to keep the machine cool and to reduce dust in the air. The roof of the tunnel is held up by steel rods and cables. Every morning, the integrity of the tunnel has to be inspected to ensure safety. There is a rift in the roof – a bad sign. Rock falls are always a risk.

Platinum ore is extracted through the process of drilling and blasting. The drill operator bores a hole of about 1.5m into the side of the rock face, explosives are inserted, and the ore is blasted from the earth. This ore is processed to extract the metal.

Rock drilling is intense physical labour that continues for long hours. A drill operator has to squat to use the drill, and the noise is deafening.

The drills the miners use are pneumatic, exerting a force dependent on the strength of the miner, who must drive the drill in while simultaneously keeping it in place.

They let me operate a drill. As I pulled back the lever on top of the machine to start the drilling, the shock of the jack hammer nearly knocked it out of my hands. The vibrations and the deafening noise as the drill bit hit the rock was overwhelming. The operator laughed and helped me to hold the drill while it chewed away at the rock face. I could not hold onto it alone.

The pneumatic drill is outdated technology, however, according to a mine drill specialist who spoke off the record. Elsewhere, these machines have largely been replaced by hydraulic drills, which are much safer to use. Powered by water pressure, hydraulic drills are held in place mechanically. The pressure exerted on the rock face is supplied by machine power and the drill operator simply has to use the controls on the machine to manage drill speed and pressure. There is also less noise and dust.

By contrast, pneumatic drills pose a greater danger to the miner. Injuries to the wrist and other joints are typical, and hearing loss and respiratory problems are also a much greater risk. Simply put, these machines take a tremendous toll on the human body.

I sent Lonmin questions about the type of drills used, and the steps they take to preserve and improve rock drillers' health. The company had not responded by the time this was published.

When I left, the friendly men thanked me for visiting. I am not sure why they were thankful. Perhaps they thought I could tell their story and improve their situation. Instead newspapers filled with news of the deaths of men like these. Too late. In the dim light of the tunnel, I could barely make out the faces of these men – men who are crucial to the survival of our mining industry and economy, and on whose tired shoulders the wellbeing of all South Africans rests. I can only hope that none of their names appeared on the list of those who died in Marikana.

Heidi Swart is the Eugene Saldanha Fellow in social justice reporting, sponsored by the Charities Aid Foundation, Southern Africa.

* Pics by Madelene Cronjé