Margaret Thatcher fought the unions and the European Union and implemented dramatic changes.

The human mind does not accept change easily. We are programmed to be secure inside the box and avoid confrontations. These are a few reasons why a crisis is not only good, but also absolutely necessary.

We know by looking at South Africa, Europe and the United States that the only way to get a mandate for change is through a crisis in which action is not driven by a desire, but rather by a need for change.

The irony is that when we are in crisis we are more efficient, work harder, become more innovative and are better able to perform under the stricture of "less is more". We are terrible risk-takers and decision-makers when we are in a period of growth, wealth and personal success.

These simple but true rules apply to South Africa and its challenges today. South Africa is a young person. Born in 1994, it is now moving from adolescence into young adulthood. With this change comes responsibility – when young and free, everything is about your needs and children are the most egocentric personalities.

When you become a young adult, you need to start showing responsibility and educate yourself. I see South Africa as an extremely successful young adult who needs to understand that the teenage years have passed and if its school performance does not improve, it is unlikely that university will be next.

South Africa needs to find its own mandate for change. The unemployment rate of the youth and the bloated public sector, both in numbers and in salaries, are taking away money from investment and much-needed infrastructure improvement. South Africa needs more energy sources – better ones too – and it needs to continue to build harbours and roads. That's the demand of a young nation and its move towards permanent and stable growth.

Main investors

Right now South Africa is falling behind the average sub-Saharan growth, the unions are too strong for their own good and the government is more focused on the ANC presidency than on creating a long-term plan for South Africa.

Things have been good, too good almost, since 1994. In the early part of this downturn, the government could afford to provide a stimulus because its fiscal position was sound; the main investors, China and the US, had plenty of cash to go around, cushioning the South African economy while the world still needed its resources. A perfect hedge against the global slowdown, right?

The global crisis is now in its fifth year and South Africa and most other countries cannot expand the fiscal stimulus because they have overspent in recent years. Foreign direct investment might still be coming in but with a high price tag – increased current account deficits – and commodity prices are dropping pretty hard. South Africa's great advantages have been its resources and its mines, but this could become an Achilles heel if the rest of the economy does not make a hand-over in terms of creating jobs and consumption.

This is where a crisis comes in handy. When the engine of an economy starts up, there is more capital available for other growing industries, the micro-economy takes over and starts to create small successes in the small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Any country with long-term growth and success has been built by them. The world's richest nations – Switzerland, Singapore, Denmark, Sweden and even Germany – have a huge dominance of them. The European Union does regular studies on SMEs and has found that, on average, in the "rich northern countries" 63% to 66% of all jobs are in the SME sector. Furthermore, 85% of all new jobs from 2002 to 2010 were created by small and medium-sized companies.

South Africa needs to embrace this and work towards reducing its heavy dependency on mining. There is nothing wrong with mining per se, but a long-term plan needs more evenly distributed income channels.

V-shaped recovery

A crisis also involves a V-shaped recovery in which growth is exponential. So you need a crisis to restart the economy. We like to call it a forest fire – it burns down the old trees, fertilises the ground and resets nature.

The present crisis in Europe has great analogies with South Africa. Greece, Portugal and Spain came out of dictatorships in the 1970s. In other words, their present democracy is only one generation old. Have you ever met a 40-year-old who did not make mistakes? Of course not. New beginnings are part of history and so is trial and error. Spain as a nation has been bankrupt 14 times, so history tells us that a country will swing like a pendulum from excess to austerity, from growth to crisis, from tailwind to headwind. It is all part of a cycle and can counted on, but how one reacts to these swings dictates how a nation develops.

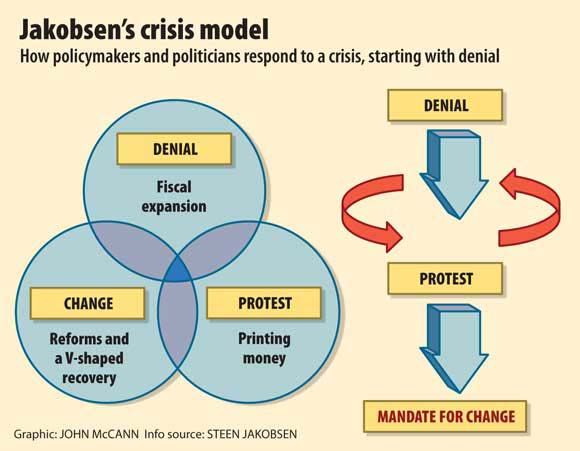

The dynamics of a crisis also tells us why and how a crisis works. (See the graphic on this page, which I have called Jakobsen's crisis model.)

Any government will always start by denying there is a crisis – the denial. It will claim it's temporary, caused by external factors and, if everything goes wrong, the South African government can always blame it on Greece. The policy response is to print money, as South Africa did in 2009.

A year or two later, the "non-crisis" is still a crisis, but most likely the voters will have changed the government or at least forced some government changes. The new government will then say: we wanted to do some fiscal stimulus (spend money we don't have) but the prior government already did this. So, instead, it will lower interest rates, weaken the currency and "print money if possible" – the protest (South Africa 2012).

Mandate for change

What South Africa, Europe, Asia and the US need is a real mandate for change, but as you know from history, the policymakers and the politicians will continue to move from denial to protest and back to denial, in a never-ending cycle until the crisis is big enough to force the need for a mandate for change.

The last mandate given and taken by a politician that I can remember happened in 1979 when Margaret Thatcher took over the then "sick man of Europe", fought the unions, fought the EU and implemented dramatic changes in British society. It was combined with a strong mental change of attitude and herein lies the final reason why a crisis is good.

A crisis is at least 50% mental. If someone has the vision and the character to force an agenda of positive change, the exercise of ending a crisis becomes relatively easy because the human mind loves to be part of something successful.

So, embrace the ongoing crisis, but also realise that, to get out of it, you need to commit to yourself, your company and your country to being part of the solution and not play the popular role of the unwilling. Forza, South Africa!

Steen Jakobsen is chief economist of Saxo Capital Markets