Forty percent fewer South African children are being hospitalised for pneumonia and severe diarrhoeal disease than in 2009 due to the government's introduction of rotavirus and pneumococcal vaccines, according to Shabir Madhi, the executive director of the government's National Institute for Communicable Diseases.

Madhi said pneumococcal disease and diarrhoea were the two most common causes of death in children under five in Africa. "Due to the introduction of the vaccines, under-five mortality has been reduced by 10% in South Africa," he said.

According to Madhi, Rotarix, which protects against the rotavirus, which causes diarrhoeal disease, and Prevenar, which protects against pneumococcal meningitis, pneumonia and middle-ear infection, have reached an estimated 85% of children in the country.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates the coverage as somewhat lower, at just more than 70%.

"Seven hundred and fifty thousand children have been vaccinated each year since 2009, if calculations are based on the WHO figure, a total of three million children over the past four years," Madhi said.

In 2009 the South African government became the first in Africa to introduce Prevenar and Rotarix vaccines into its public immunisation programme.

Since then the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (Gavi), a private-public partnership that provides developing countries with free vaccines for an initial five years, has brought these vaccines to many other African countries. In 2011 alone, Gavi rolled out the pneumococcus vaccine in Kenya, Mali, Sierra Leone, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Gambia, the Central African Republic, Cameroon, Rwanda, Burundi, Ethiopia and Malawi.

The South African government funds Prevenar and Rotarix itself, however, as the country does not qualify for Gavi assistance. The alliance assists only countries that have a per capita income of $1000 or less a year. Prevenar and Rotarix take up R900-million of the government's overall R1.2-billion vaccine budget. The government buys Prevenar at $19 a shot (three are needed) and Rotarix at $7.5 a dose (two shots are needed).

Ironically, Western countries such as the United Kingdom will only introduce a rotavirus vaccine in July and has not yet added a pneumococcal vaccine to its immunisation schedule.

Prevenar

Prevenar reduces the risk of pneumococcal disease – pneumonia, middle-ear infection and meningitis caused by the extremely contagious bacterium streptococcus pneumonia – by 85% in HIV-negative children under five.

Madhi said that, although many children would not develop the disease, those children with "underlying predisposing factors", such as pollution, malnutrition, being exposed to passive smoke and being HIV infected, were at major risk.

According to the Actuarial Society of South Africa, 3% to 4% of children under five in the country are HIV infected. Such children are significantly more likely to develop pneumococcal disease as HIV weakens the immune system considerably.

Madhi said Prevenar reduced by 65% the risk of children with HIV developing severe pneumococcal disease. The government's introduction of free antiretroviral treatment for all HIV-infected children under one year in 2009 may have reduced this risk even further because, "with antiretroviral drugs, their immune response to the vaccine is as good as HIV uninfected kids, which suggests that the benefits would be similar".

Rotarix

According to Madhi, diarrhoea kills 25 South African children under five each day – a total of 8000 a year – before the introduction of the rotavirus vaccine.

He is researching the impact of Rotarix on hospitalisation in three South African hospitals in Cape Town, KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng.

In Ngwelezane Hospital in KwaZulu-Natal, the under-five mortality rate is about three times higher than that in Soweto. "[Despite this], they have literally closed down the Ngwelezane Hospital ward that deals specifically with diarrhoeal disease, the gastrointestinitis ward, as a result of the introduction of the vaccine," Madhi said. (See below.)

The Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto has experienced a decline of about 40% in diarrhoeal hospitalisations.

Coverage

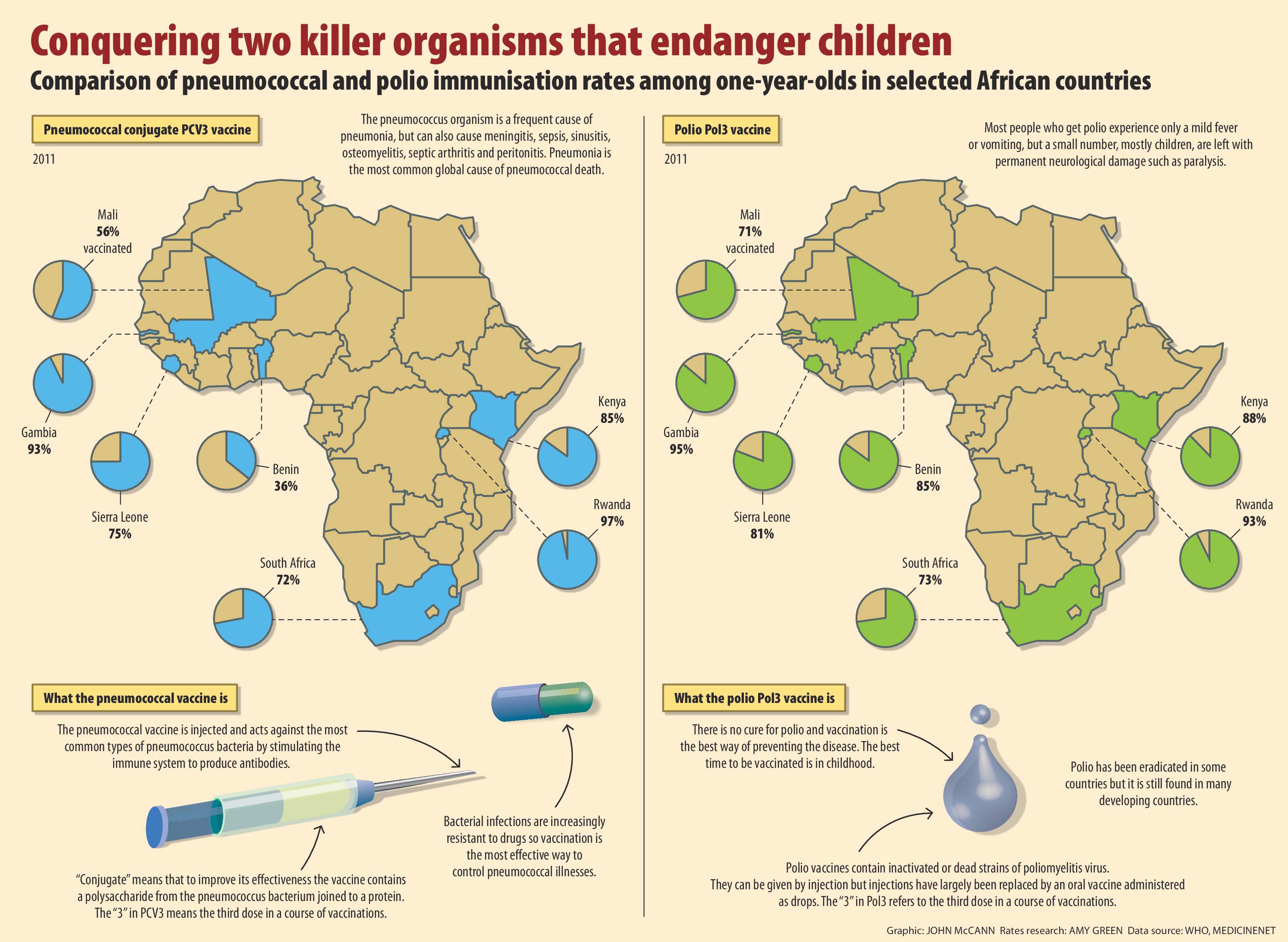

However, South Africa's estimated vaccine coverage is often considerably lower than that of poorer African countries. For instance, Rwanda's coverage for Prevenar is 97%, Kenya's 85% and Gambia's 93%, compared with South Africa's 72%.

Another example is the diphtheria tetanus pertussis (DTP3) vaccine. By 2011 DTP3 had reached only 72% of South African children, according to Daniel Berman, general director of aid organisation Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). "In Angola, a country with half of South Africa's gross national income, the coverage rate for DTP3 is 86%. In Malawi, where the gross national income is a tenth of South Africa's, 87% are covered."

Berman said the country's low rates were "not because of a lack of spending. The country is paying the highest prices for vaccines in the developing world. We need to ask why this is so."

Julia Hill, an advocacy officer for MSF in Johannesburg, said bad logistics, regular stock-outs of routine immunisations and inadequate transportation and cold storage capacity in South Africa contributed to low vaccine coverage rates.

According to Berman, the only way to answer the vaccination challenge properly is for South Africa to conduct a survey in each province that determines actual coverage rates as opposed to estimates.

Madhi said the last survey was conducted in the early 1990s, but the health department is planning to do a follow-up survey.

According to Madhi, "the challenge is to reach the many remaining children under five in South Africa that are not covered by Prevenar and Rotarix, particularly those in rural areas".

"Many parents in rural areas expect their kids to die of pneumonia because it has happened to so many children there. The vaccines' worthiness depends on reaching children in the most marginalised communities."

___________________________________________________________________________________

KwaZulu results breathtaking

It was July 8 2011 and the team had begun to worry. It was conducting a study to find out how many children were being hospitalised for severe diarrhoeal disease and the site at Ngwelezane Hospital in KwaZulu-Natal had not reported back to it since May. The team had been working too hard for anything to go wrong.

"In 2010 we had cases from all three sites," said Shabir Madhi, executive director of the National Institute for Communicable Diseases, the organisation conducting the study.

"In 2011 we simply did not get any more cases from Ngwelezane, or very few, so we contacted the head paediatrician, Dr Constance Kapongo, to find out what the problem was," he said.

It was especially troubling because, according to Madhi, the peak season for hospitalisation for severe diarrhoeal disease is between April and July.

"His reply to my query was simply an email with an attached photograph of an empty ward," Madhi said, unable to control a smile. "We were shocked. This was such great news."

In early 2009 the health department introduced two new vaccines into the public immunisation programme that were responsible for this drastic impact.

The first was the Rotarix vaccine, which protects against severe diarrhoeal disease caused by rotavirus. The second was Prevenar, to protect against pneumococcal-related diseases like pneumonia, meningitis and ear infection.

According to Dominique Stott, a vaccine expert from the Professional Provident Society, a financial scheme for professionals, vaccines strengthen the body's immune response to specific diseases.

"When a vaccine is introduced into the body the body will produce antibodies to fight that specific pathogen.

"So if, at a later stage, the body comes into contact with that pathogen, whether it's breathed in or swallowed, the body is better able to protect itself from infection."