The mining industry is in the doldrums. Declining metal prices and rising costs foreshadow a tumultuous time ahead for the sector which is still reeling from devastating wildcat strikes last year.

Yet mining bosses continue to rake it in – with one individual taking home much as R45-million last year – serving to fuel the ideological war between themselves and their workers, the haves and have-nots, particularly as wage negotiations and the strike season kick into gear.

Last year, the chief executives of just the top three gold and platinum miners in South Africa earned collective remuneration totalling R140-million, leaving workers and unions indifferent to pleas of poverty by mining houses in ongoing wage negotiations.

Peter Major, a mining analyst at Cadiz Corporate Solutions, said executive remuneration would continue to add fuel to the fire when it came to wage negotiations.

He said many senior directors and many in management had a short-term, selfish view, which, he felt, let a proud 150-year-old industry down.

“If these guys wanted workers to take a zero percent increase, the first thing they would do is take a pay cut. That’s what leading by example – from the front – is all about. Instead, many of these ‘leaders’ are taking increases and bonuses. And when viewed against the enormous and frequent write-downs we’ve been seeing, resignations, firings and jail time should be up for serious consideration. It’s atrocious.”

Opening offer

On July 15 gold employers tabled an opening offer of a 4% wage increase, which was swiftly rejected by all worker representatives at different levels, who have demanded anything from a 10% to a 100% increase.

The parties reconvened on July 24 for another round of tough talks in which the offer was revised up to 5%, after which Solidarity, UASA (formerly known as United Association of South Africa) and the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) declared a wage dispute that will be referred to the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration.

But gold producers say they simply cannot afford the increases. The Chamber of Mines’s figures for the fourth quarter of 2012 show – based on cash costs and an average gold price – that almost half of the country’s gold mines are unprofitable or marginal, at best.

But executive pay, at least for the major players in the sector, remains sizeable, as confirmed by company remuneration reports for 2012.

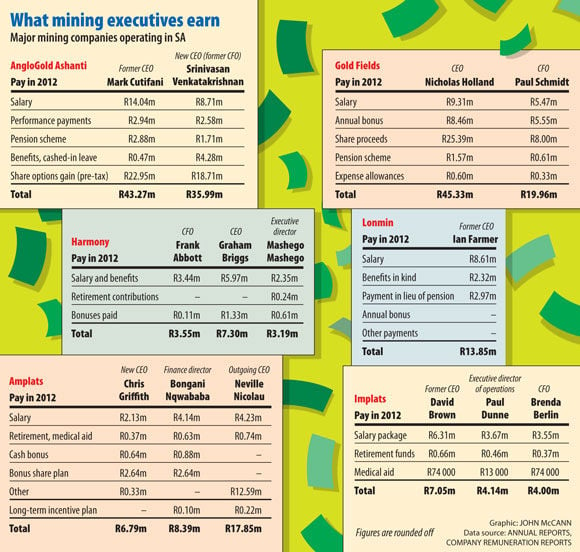

Top of the list is Gold Fields chief executive, Nicholas Holland, who earned a basic salary of R9.3-million, but after bonuses, share proceeds and other benefits, took home R45.3-million – R12.6-million more than the year before. Gold Fields chief financial officer Paul Schmidt took home almost R20-million.

Speaking to the media in May this year, Holland outraged unions when he said: “We can’t continue giving double-digit increases when productivity is declining. That’s not sustainable.”

"Fuelling a class war"

NUM spokesperson Lesiba Seshoka said comments like Holland’s, in light of his own salary increase, was “fuelling a class war”.

AngloGold Ashanti’s former chief executive, Mark Cutifani, took home R43.2–million last year, while the company’s chief financial officer and now chief executive, Srinivasan Venkatakrishnan, was paid a total of R36-million.

Graham Briggs, the chief executive of Harmony, the smallest of the top three gold miners, took home R7.3-million for the 2012 financial year, somewhat less than the R7.9-million he received in 2011.

Harmony chief financial officer, Frank Abbott, racked up R3.5-million, higher than the R1.2-million he earned in 2011.

Wage negotiations in the platinum sector are yet to begin, but executive pay will most likely remain one of the unions’ bargaining tools.

Lonmin’s former chief executive, Ian Farmer, who stepped down due to illness in December 2012, earned R13.8-million for the year ended September 30 2012, compared with R17.9-million for the year before.

Millions of rands paid out

Impala Platinum’s Dave Brown, who stepped down in June 2012 and was replaced by Terrence Goodlace, took home R7-million – R400 000 less than the year before.

Chief financial officer Brenda Berlin was paid R4-million, while Paul Dunne, the executive director of operations, earned a total of R4.1-million.

Anglo Platinum’s chief executive, Chris Griffiths, who was appointed on September 1 last year, received total remuneration of R6.7-million, while his predecessor left with R17.8-million.

Finance director Bongani Nqwababa earned a total of R8.4-million, including his basic salary of R4.1-million.

Gideon du Plessis, the general secretary of trade union Solidarity, said the remuneration was “exorbitant”.

“I understand the fiduciary duty they have and the difficulty of the task … but if you compare the remuneration of entry level workers to executives, there is a 100% mismatch. It conflates the perception that they do have the money.”

Other factors at play

But Loane Sharp, a labour analyst at Adcorp Analytics, said there were a number of other factors at play. Age and experience, qualifications, skills and performance against directors’ objectives also mattered.

“When a company doesn’t perform well, it doesn’t mean the chief executive should get nothing, they may well get increases for those other reasons,” Sharp said.

He said union claims that workers’ increases should be connected to bosses’ increases were self-serving.

“Opportunistically, unions pick whatever factor suits the biggest wage increases … sometimes it is the cost of living, sometimes chief-executive remuneration, sometimes it’s the spread of short-term lending.”

Productivity was what should matter and productivity was weak, he said. Charmane Russell, the spokesperson for the gold producers in the wage negotiations, said there were a number of factors to consider.

First, a calculation of the major chief executives’ pay showed that their earnings at gold mining companies in South Africa last year – excluding share options, but including bonuses – amounted to 0.37% of total employee pay.

Sought-after skills

Importantly, mining chief executives, who were in short supply and in demand globally, brought with them very specific and sought-after skills and took on enormous responsibility, Russell said.

“These factors and the performance of their companies determine what chief executives earn. If South African-based mining companies did not pay global market-related salaries to executives, it is likely people would go elsewhere. This would be dire for the South African industry.”

Russell said South African mining chief executives were, in reality, heads of global mining companies, so the global remuneration base and globally competitive salaries needed to be considered. Also worth noting, she said, was that chief executive pay was determined by shareholders.

Typically, a large portion was dependent on the achievement of very specific outcomes and on the performance of the company’s own share price.

Russell also said a number of companies had put in place measures to cut costs. At both Sibanye Gold and Gold Fields, a salary freeze was implemented last year for top managers, including the executive leadership, and would continue this year.

The companies had also introduced voluntary separation packages and had subsequently reduced management levels significantly.

Salary packages

Gold Fields spokesperson Sven Lunsche said the salary packages were share related, which made remuneration look significant last year, “but that can go up and down and I expect, over the next few years, it could be dismal”.

Major, of Cadiz Corporate Solutions, said a salary freeze was a “good start” and set a good example.

“But a 5% cut would have shown real urgency and seriousness. And let’s be honest, which executive couldn’t handle a 5% cut in his stride?”

Lunsche said an involuntary pay cut for a chief executive could have a number of repercussions for the company should the executive wish to take legal steps. Seshoka said a salary freeze meant little.

“Mining bosses have never had any good gestures, the only gesture they show you is that they smile while you are in pain … If there is not a complete change in the manner they run their business, there will never be peace in the sector.”