Robert Mugabe, the man at the centre of the Zimbabwean story for the past four decades. (Reuters)

The story of Zimbabwe is the story of the suit: the three-piece suit and the double-breasted suit, the dinner suit and the lounge suit. It is the tale of the garment in its various vent iterations, be it single vent, ventless or double vent.

Or, alternatively, and perhaps more accurately, we could say the story of Zimbabwe's revolution could be told as the story of suited white men laying claim to a piece of country. It is also the story of black men first enthusiastically embracing the suit and all that is attendant upon it and then melodramatically discarding it. They exchanged it for the Mao suit, guerrilla garb and military fatigues, which, in turn, when the times demanded a different dress code, were also cast aside.

Robert Mugabe, the man at the centre of the Zimbabwean story for the past four decades, typifies this love-hate relationship with the Western suit.

"I felt that I was a revolutionary, militant and so on," Mugabe told the historians David Martin and Phyllis Johnson in their book Struggle for Zimbabwe, which came out in 1981, about the period immediately after his return from Kwame Nkrumah's Ghana in the early 1960s.

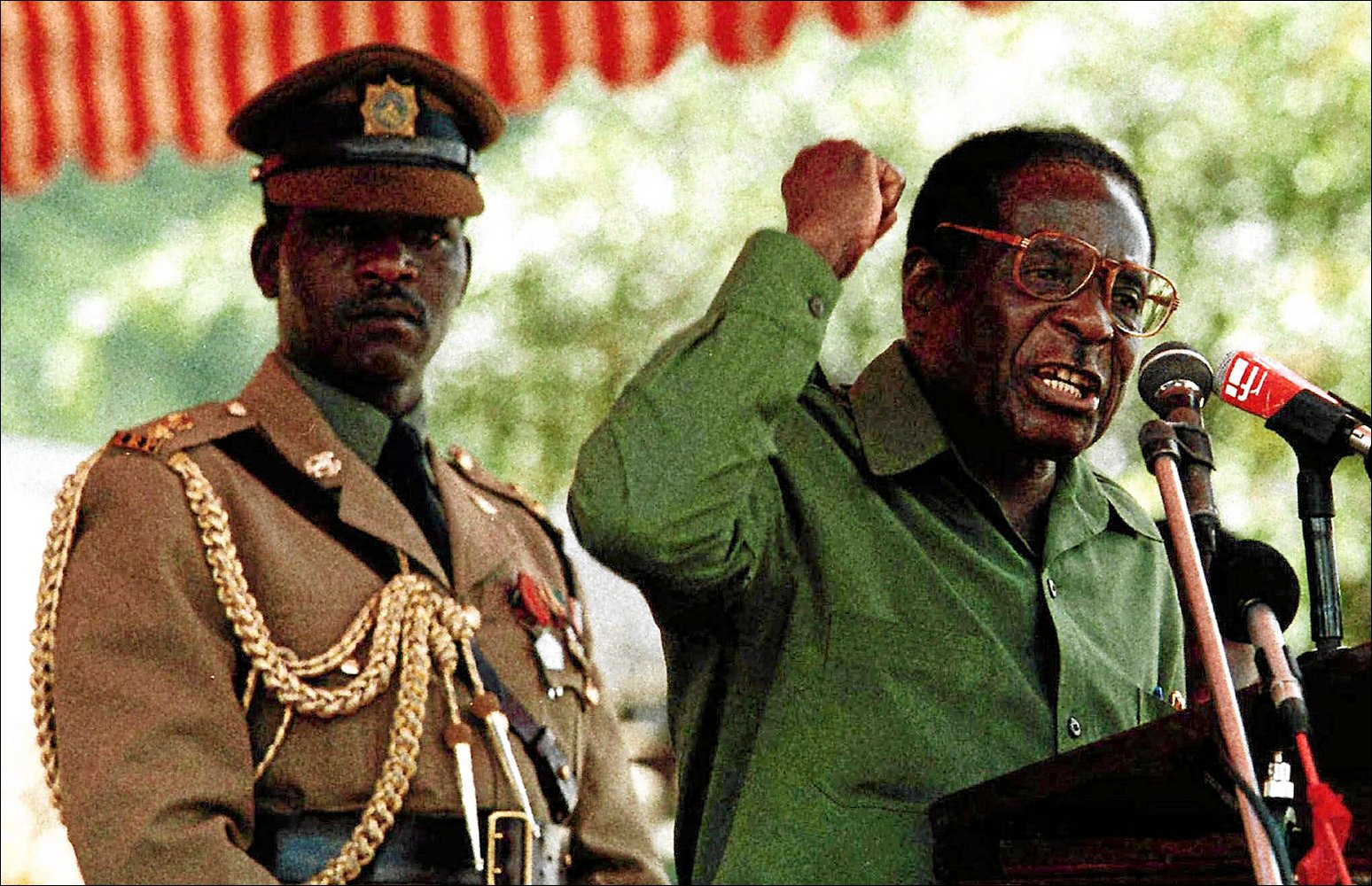

All the bells and whistles: President Robert Mugabe at the opening of Parliament in 2003. (AP)

All the bells and whistles: President Robert Mugabe at the opening of Parliament in 2003. (AP)

In a sense he was right. The nationalist fight until then had been civil and genteel, but after countless lobbying, as one analyst cynically put it, all the besuited nationalists had to show for it was permission to drink "European" liquor.

It's possible that Mugabe's incendiary speech of 1964 was the harbinger of the armed struggle that would begin in earnest a decade later. It's not a coincidence that the suit is the centrepiece of the tale.

The speech-cum-performance art, art-cum-melodrama, was staged at Zanu's inaugural congress of 1964 held in Gweru, Zimbabwe's third city. The late political scientist Masipula Sithole was there. He is the younger sibling of Zanu's founding president, Ndabaningi Sithole.

Cowboy government

Sithole wrote in a newspaper column in the late 1990s that Mugabe cast off his jacket while simultaneously labelling Ian Smith's Rhodesian Front administration a "cowboy government". Mugabe charged: "If I must lose my freedom because of these so-called civilised clothes the white man brought, then he can have them back and I have my freedom!"

After discarding his suit jacket, Mugabe then removed his tie. When he was about to take off his shirt, those assembled, realising his trousers would soon be lying in a heap on the podium if they didn't stop him, shouted as one: "No, you have made your point."

But Mugabe hadn't really made his point; he had just begun.

"The leader of the cowboy government, Mr Ian Smith, says 'there will be no majority rule in my lifetime and not in a thousand years'. Now, this is dangerous talk. If my freedom depends on Mr Smith's lifetime then I have no choice but to cut it short".

Mugabe was charged with sedition and uttering "subversive statements" and sent to prison for a year.

Mugabe had shown, to be sure, his pugilistic side before. But it had been for narrow, self-serving ends. When he was growing up in Kutama, 80km southwest of Harare, he used to box regularly. He studied to be a teacher at Kutama before he left for Fort Hare to study for an undergraduate degree.

Mugabe and his first wife Sally with Canaan Banana and his wife Janet in 1980. (AFP)

Mugabe and his first wife Sally with Canaan Banana and his wife Janet in 1980. (AFP)

When Mugabe qualified as a teacher, he almost beat up Garfield Todd – then his principal and later a prime minister of Southern Rhodesia – for deducting 60p from his monthly salary of £3. Todd had unilaterally deducted the amount to cover the tuition fees one of Mugabe's students hadn't paid.

After his release, he was again detained until 1974. Sarah, his Ghanaian wife, now deceased, was charged, in the words of Johnson and Martin, with "bringing the Queen's name into 'dis-esteem' for saying she was doing nothing to help the Africans".

The Maoist suit

At the prison doors, they took away Mugabe's suits in exchange for government-issued prison garb. He was in prison for a decade.

When, exactly, Mugabe started to wear the Maoist suit isn't clear. In the years leading up to his imprisonment, Mugabe wore Western suits. When he came out of prison, the pictures available suggest a shift in sartorial tastes. The leaders of the states propping up the Zimbab-wean revolution might have provided direction. Julius Nyerere of Tanzania wore the safari suit and so did Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia. Samora Machel, Mozambique's founding president, wore military-style shirts and caps.

Perhaps it was a strategic decision to wear their ideology. Zanu was supported by Mao's China and the guerrilla training camps in Tanzania were staffed by Chinese instructors.

But for someone willing to theatrically throw away his suits, Mugabe has maintained close partnerships with men whose livelihood revolves around them.

One of the men was Bhula Bhagat, who ran a grandiloquently named shop in Harare known as the House of Nargaji. Their friendship went back to December 1960, when Bhagat sold Mugabe a pair of shoes, and continued into the post-independence era.

Khalil "Solly" Parbhoo, Mugabe's other tailor, told the late Heidi Holland in her book, Dinner with Mugabe, that the president "still dresses like an English gentleman; that's always been his style. He acts like an English gentleman, too, a wonderful person when you are in his presence, although not when he's on the public platform. You can't believe he's the same person you see on the stage, shouting this and that."

Mugabe, perhaps not surprisingly, is a fastidious client.

Turn-the-other-cheek Mugabe

"I made him a jacket once, which should have been double-breasted, but he didn't like it at all. He knows what he wants.

"One of his aides used to come into the shop to choose a few swatches, which I would take to State House for his final selection. He goes for dark cloth, sometimes with a stripe or a check. He likes vents on the sides of his jackets … He needs a few vents to let out the hot air!"

In army fatigues at an election rally in 2000. (AP)

In army fatigues at an election rally in 2000. (AP)

But it hasn't always been so. In 1980, while wearing a single-breasted suit, Mugabe gave his first address as executive prime minister.

He said: "If yesterday I fought you as an enemy, today you have become a friend and ally with the same national interest, loyalty, rights and duties as myself. If yesterday you hated me, today you cannot avoid the love that binds you to me and me to you."

It was a speech that shocked the whites who hadn't yet crossed the Beitbridge border post into South Africa. This wasn't what they had expected. The nightmares of most must have featured the Marxist guerrilla leader shepherding them into gulags, lining them against the wall and bayoneting them.

He continued, perhaps with a demeanour befitting a besuited gentleman who doesn't want to dirty his suit: "Is it not folly, therefore, that in these circumstances anybody should seek to revive the wounds and grievances of the past? The wrongs of the past must now stand forgiven and forgotten. If ever we look to the past, let us do so for the lesson the past has taught us, namely that oppression and racism are inequities that must never again find scope in our political and social system. It could never be a correct justification that, because whites oppressed us yesterday when they had power, the blacks must oppress them today because they have power."

This conciliatory and turn-the-other-cheek Mugabe is the one who Queen Elizabeth knighted in 1994, an honour later taken away when Mugabe was fighting for his political life against Morgan Tsvangirai's Movement for Democratic Change. On the day, Mugabe was wearing a dark suit, a white shirt and a bow tie.

Pursuing nationalisation

The Mugabe who was knighted must be the same one who amazed former secretary general of the Commonwealth Don McKinnon with his knowledge of arcane New Zealand cricket trivia. It must be the same Mugabe who gushed in 1984: "Cricket civilises people and creates good gentlemen. I want everyone to play cricket in Zimbabwe; I want ours to be a nation of gentlemen."

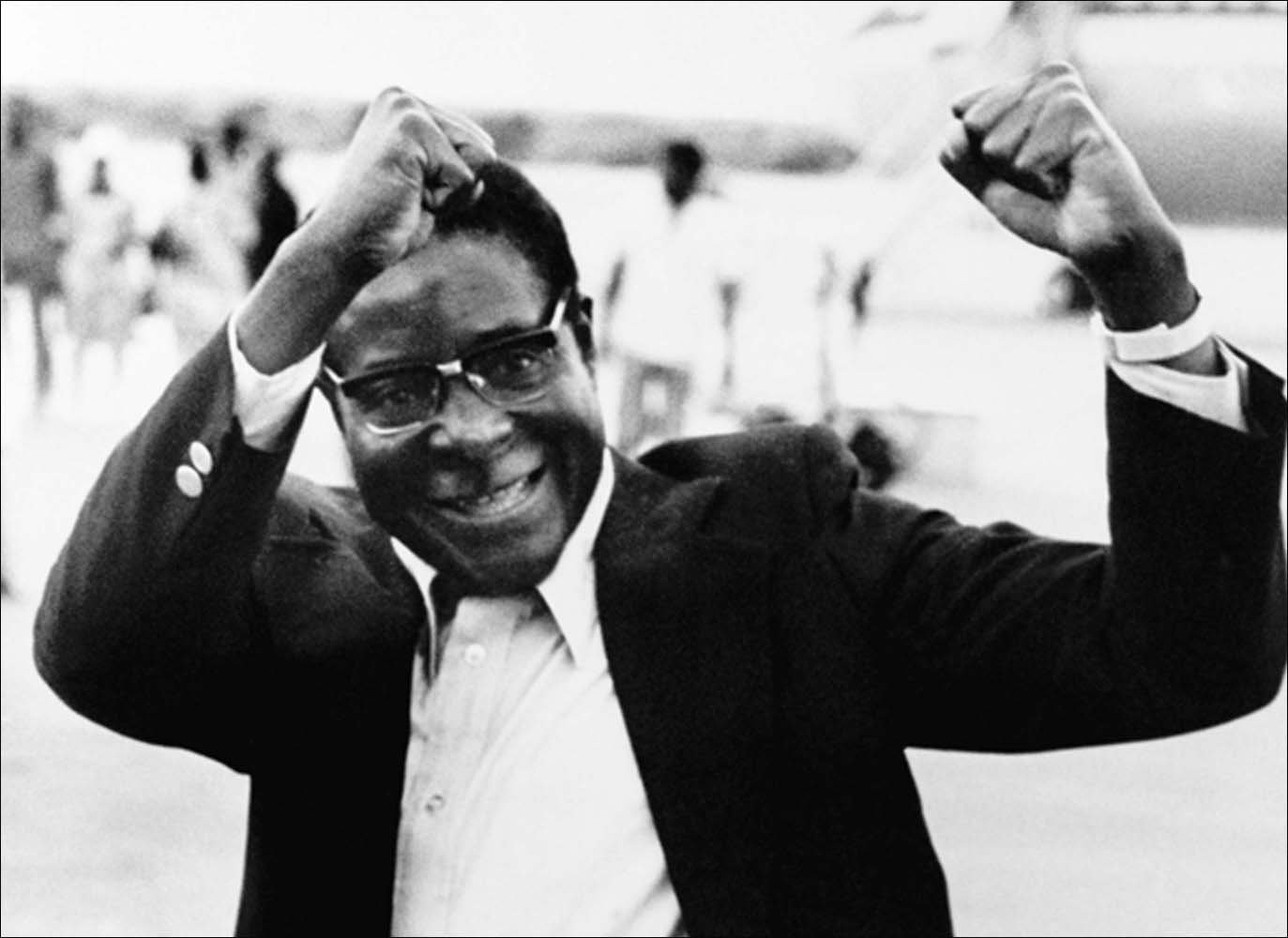

Mugabe looking spritely in 1977. (AP)

Mugabe looking spritely in 1977. (AP)

In the 1990s, Mugabe noticed, to his horror, how more and more Zimbabweans were choosing dreadlocks instead of his close-cropped, kempt look. He exhorted them to emulate Bob Mugabe's hairstyle instead of Bob Marley's. In fact, as recently as last year, Mugabe declared while pursuing nationalisation policies: "The men want to sing and don't go to colleges. Some are dreadlocked."

Marley performed at the independence celebrations of 1980. So enamoured was the reggae icon with the country and Southern African anti-colonial struggles in general that he even composed a song, Zimbabwe, to celebrate the guerrilla war for freedom.

This statesmanlike Mugabe was markedly different to the guerrilla leader of the 1970s. There is a grainy picture of Mugabe in combat gear. His arms are at his sides, his sleeves rolled up and a beret on his head.

In the years leading up to the signing of the 2008 pact that brought the MDC into government there was a tendency to talk about a military coup in Zimbabwe. Analysts expressed reservations about the appointment of soldiers and ex-military types to parastatals such as the Broadcasting Authority of Zimbabwe, the Grain Marketing Board, the Minerals Marketing Corporation of Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe Broadcasting Holdings, Zimpapers and the National Railways of Zimbabwe.

It's not far-fetched to compare how the military took over these public insitutions with what happened in the bush of Mozambique in the 1970s. In fact, in 1976, Mugabe himself theorised about the unity of the gun and the vote.

"Our votes must go together with our guns. After all, any vote we shall have shall have been the product of the gun. The gun which produces the vote should remain its security officer – its guarantor. The people's votes and the people's guns are always inseparable twins."

Mao suits and guerrilla attire

There is, then, little point in wondering why Zanu-PF has always approached elections as if they were warfare, deploying soldiers, war veterans and assorted militia. "The gun which produces the vote should remain its security officer – its guarantor." This template was one to which he would return in the elections of 1985, 2000, 2002, 2005 and in 2008.

But let's go back to the 1970s, around the time when Mugabe started wearing Mao suits and guerrilla attire. Mugabe attacked Kaunda without using diplomatic speak. It was almost as if he was talking to just another guy, not the president of a state actively supporting the Zimbab-wean war effort.

On a motorboke in Berlin in 1998 with his wife Grace. (AP)

On a motorboke in Berlin in 1998 with his wife Grace. (AP)

In a January 1976 radio interview with the BBC in London recorded by Martin and Johnson, he attacked Kaunda in language reminiscent of his recent spats with Tony Blair and George Bush.

Mugabe said: "Well, I think President Kaunda has been the principal factor in slowing down our revolution. He has arrested our men, locked them up, and within his prisons and restriction areas there have been cases of poisoning, and there have also been murders."

Interviewer: "By who?"

Mugabe: "By his men. By Kaunda's army."

Interviewer: "You have proof of that, do you?"

Mugabe: "Yes, 13 of our people were shot dead, cold bloodedly. And one cannot regard this as an act of conforming to the principles of humanism."

By most accounts, the speech won him support among guerrillas who were a bit wary of the bespectacled nerd who had just taken over leadership of Zanu.

Military fatigues

From then on, the war intensified, resulting in a reluctant Smith agreeing to the principle of one-man, one-vote, which he had sworn would never happen, not "in his lifetime, not in a thousand years".

So it was that the black nationalists and Smith's Rhodesian Front found themselves at Lancaster House in west London trying to come up with a deal that would bring peace and majority rule to the former British colony.

But Smith was still alive and, unlike the Biblical Methuselah who was 969 years old when he died, the stubborn white minority leader was just 60.

For that occasion, at least for the signing of the actual agreement, Mugabe discarded his Mao suits and military fatigues for a Western-style suit.

But with independence the Mao suit was soon back. At a rally in Norton in 1982, a small town 40km south of Harare, Mugabe accused the Joshua Nkomo-led PF Zapu of plotting to topple his government. In the photo, fist clenched like a boxer, Mugabe looks intense. Under the greyish Mao suit, the flaps of the pockets buttoned down, Mugabe is wearing a formal shirt and striped tie.

In Matabeleland, in southern Zimbabwe, Mugabe said: "We have to deal with this problem quite ruthlessly … don't cry if your relatives get killed in the process … where men and women provide food for the dissidents, when we get there we eradicate them. We do not differentiate who we fight because we can't tell who is a dissident and who is not."

This wasn't just loose, unhinged talk to appeal to heated supporters at a rally. In a sober address to Parliament in 1982, Mugabe was equally forthright: "Some of the measures we shall take are measures which will be extralegal. An eye for an eye and an ear for an ear may not be adequate in our circumstances. We might very well demand two ears for one ear and two eyes for one eye."

By the time of the 1987 Unity Accord that stopped this genocide and brought Nkomo into government, 20000 Ndebele civilians had been murdered.

'Smartening up Mugabe's wardrobe'

But when was the Mao suit discarded for the Saville Row? Did it coincide with the adoption of the Economic Structural Adjustment Programme (Esap) in 1991, a neoliberal programme demanded by the International Monetary Fund? The decade of fat enjoyed by a majority of Zimbabweans had seen hundreds of thousands of young people go through the school system, the construction of roads and clinics. But with the introduction of the Esap, government subsidies on basic goods, university education and health were removed. The people were forced to pay whatever the markets demanded.

In my mind – and I could be wrong – these two events are conjoined. But, from then on, all I remember is Mugabe in Western suits. Gone forever was the Maoist garb that harked back to a different world. Did it have something to do with the fall of the Berlin Wall?

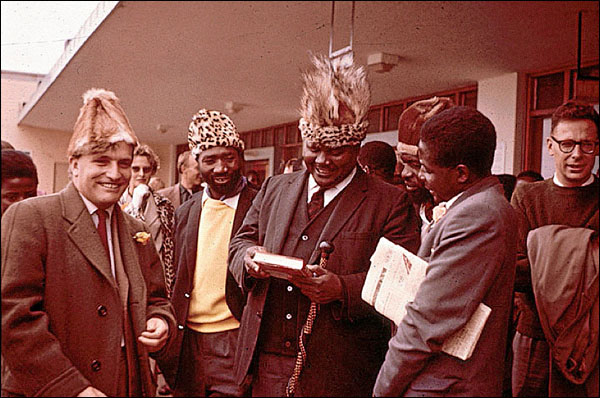

Nationalist historian Terence Ranger, Maurice Nyagumbo, Joshua Nkomo, James Chikerema and Robert Mugabe in 1961. (David Wiley)

Nationalist historian Terence Ranger, Maurice Nyagumbo, Joshua Nkomo, James Chikerema and Robert Mugabe in 1961. (David Wiley)

I asked Zimbabwean historian and journalist Iden Wetherell when this happened. He said he couldn't recall the exact moment. Instead, he drew my attention to a 1999 photo of Mugabe astride a German motorbike while his wife Grace is "looking on and smiling". Wetherell told me the stylish Grace is credited with "smartening up his wardrobe".

Of course, when it's election time, Mugabe discards the suit for the colourful cotton shirts printed with his image (let's just call them Mugabe shirts). The party faithful, taking their sartorial cue from the leader, also don this self-adoring electioneering garb.

There is an image from the early 2000s in which Mugabe sports an army-type green shirt. It's at an election rally during the violent elections in which Mugabe almost lost his power to the Tsvangirai-led MDC.

One wants to say Mugabe wears the suit that references the times until one realises that the Western suit – even as he took back land from the white farmers and majority stakes of companies based in Zimbabwe – remains his dress of choice.

Perhaps the man, born in 1924, is too tired and old to keep up with the fashion trends of the day so he now goes about in a trusty dark suit. You can't go wrong in a dark suit.