In many respects, the World Bank was a toxic environment, for a number of reasons that had as much to do with its organisational structure as the stressful demands of the job.

Typically, the working day started at 7am and would frequently end with a cocktail party for some visiting delegation. It would be past 10pm before I crawled into bed. Then up for a 4am flight to Bangkok with a change in time zones and a rigorous schedule of meetings. Two days later, it would be London, with a similar schedule, and then back to Washington.

Within a year, I had broken my back. Medically, my condition was known as a herniated disc and it was stress-related. Small consolation then that I was having fewer migraines. The stress had found a new vulnerability.

Those with high-stress careers who spend long hours in airplanes are particularly at risk of this condition. I was also exercising frequently in a gym and may have hurt my back there. Whichever way it occurred, it was an accident waiting to happen.

A herniated disc meant a lot of pain. When I stood or sat, the sciatic nerves were pinched, so travelling was hell. When I lay down, there was no pain, but once I stood up, there were shooting pains down my leg that were pure agony.

(World Bank head) Jim Wolfensohn had fallen victim to a herniated disc and assured me that only an operation would cure the problem. Initially, I tried physiotherapy, and then cortisone injections until, in January 2002, I checked myself into Johns Hopkins for the operation. It was successful and, although I have to look after my back these days, the pain has gone.

As a footnote, it is worth mentioning that when I first approached a doctor about my back problem, he remarked that I was another one of the casualties of the World Bank. It was known as a sick institution. Sometimes the sickness manifested itself physically; more usually priests or psychologists had to deal with staff breakdowns.

Diversity dilemma

It was an unhappy place and part of the problem was that it was a diverse institution that brought people together from more than 140 countries. Diversity is a good thing, but too much of it can be difficult to handle. There were too many people fighting their own corners without the guidance of an overall strategy.

Also, the directors were continually policed by the full-time, non-executive board members. They would second-guess the president, and they were continually pressing me to explain why I was underplaying economic development in favour of human development.

When I reversed this question and asked how they could develop a country in a sustainable way without paying attention to health and education, I received belligerent emails accusing me of disrespect. From Wolfensohn, I heard there was considerable animosity towards me, but I was there to perform a function and so I simply ignored these emails.

The way the bank was structured had much to do with its own toxicity. A full-time board meant that the staff was under constant scrutiny; in fact, they were policed.

Minor disputes could end up with a board member when disgruntled staff bypassed the management structures designed to handle their problems. This resulted in confused lines of reporting, and unhappiness. The manner of the shareholding was such that the major contributors held the greatest sway. To this end, the United States had veto power over any policy with which it disagreed – as I have demonstrated regarding higher education.

It soon became clear to me that instead of focusing on world development, the focus was on individual countries.

With more than a 140 countries represented, each country was lobbying for its slice of the pie. The appointment of vice-presidents, for instance, was supposedly done on merit, but each vice-president would come with a constituency – the region they represented. And their focus would be on that region rather than on keeping a global perspective.

For an idealist, like me, with a world vision, this was disillusioning. I discovered I was ill prepared for an environment geared to constant tension. I remember that Wolfensohn would go to each board meeting prepared for a fight. Often he would lose his temper. Most of the time he was trying to paper over the cracks and keep disparate units together. It was a difficult process to manage.

One of my fellow directors, who saw how I was struggling with the internal politics, suggested I contact an executive management coach he knew and to whom he referred colleagues. Her name was Katherine Strickland and she had experience of various organisations, including JP Morgan. She was a gem. She helped me understand that the issues were not about me, nor about the nature of the decisions I took or the actions on which I embarked. At issue was how I managed the structure. She taught me to manage those above me, those colleagues on an equal footing and my staff.

This was the first real personal development I had undergone in the latter part of my life. It helped me get much into perspective and helped me play to my strengths. I am a street fighter, and would rely on my intellectual prowess to deal with confrontation. The result was that I might win the battle, but lose the war. Katherine taught me not to undermine my strongest suit, but to empathise with the other person and win them over through collaboration. Initially, I saw her once a fortnight, then less frequently until our consultations dropped to a need-to basis.

Despite the perspective and helpful strategies provided by Katherine, the continual infighting eventually began to wear on my nerves.

Exit strategy

By 2003, I had had enough. Fortunately, an exit strategy appeared in the form of an inquiry into international patterns of migration.

Migration was an issue that the world was not dealing with well; in fact, it lurched from crisis to crisis. What was needed was an analysis of migration as an ongoing phenomenon in an interconnected world where you could track and detail the impact on financial flows or the distribution of talent. A crucial question, for example, was which countries were losing their intellectual capital and which were benefiting from this? I was co-chair of this commission and it took me back to the kind of research I loved and with which I was most comfortable.

I approached Jim Wolfensohn and suggested that this would be my last project with the bank. At the time, there was intense lobbying for reversals of some of the things that he had stood for and he was an embattled president. We agreed that this commission was an appropriate way out.

Once the report was prepared, it was presented to the United Nations. Like so many things that drift about in the United Nations, it circulated for a while, but no action was taken. But I now started travelling throughout Africa, Asia and Latin America, presenting the report, and was spending less and less time in the US. Eventually, I suggested to Wolfensohn that I base myself in Cape Town, because it was easier to travel in the continent from there than making transatlantic hops. Again, he could see the advantages, and I was partly released from the toxic institution.

I have to admit that I left Washington with mixed feelings. When my term started, I rented a house in a gated complex in Georgetown, the most beautiful part of the city. Not long afterwards, I bought a small semi-detached house in the Cloisters. The Cloisters had been part of Georgetown University, a university started by Catholic monks and built to resemble a monastery. Eventually, the church hived off this quarter and it was redeveloped into modest, but comfortable accommodation.

From my home, it was only a short walk, and one I frequently undertook, to the Potomac River or into the forest, and in spring, Washington was buoyant with new life and vitality. It was good to be alive in that place. At the time [my son] Malusi was staying with me and [my son] Hlumelo would often visit from the West Coast. Consequently, I have fond family memories of those years.

Contrary to my sentiments about Washington, I did not leave the World Bank with mixed feelings. Being there was like living in a proverbial pressure cooker, where everything was constantly on the boil.

Homeward bound

It was an attractive proposition to be going home. Not that home had been far from my activities for the last four years. In fact, I had found that I could not escape South Africa.

For instance, while I had been advocating the World Bank's progressive HIV policies everywhere in the developing world, I was constantly confronted with then President Thabo Mbeki's HIV denialism. It was an embarrassing situation.

I have come to realise that South Africa has a way of not letting go of its citizens, even when they live in distant lands.

It was a relief to return to the country. I came home equipped with the report on migration and because South Africa did not have a migration policy – and still does not, for that matter – I motivated for a discussion on migration in the hope that it would move the government towards initiating such a policy. I had the support of Dr Wilmot James, then the head of the Institute for Democracy in Africa and the head of its migration policy, and I told the minister, Nosiviwe Mapisa-Nqakula, that I would give her my full support to push this matter. It was not to happen. Inertia, ennui, the obfuscations of bureaucracy, call it what you will, but when we had a chance to formulate policy about this important international issue, we missed it. Since then, migration has fallen off the agenda.

Despite this local setback I was still travelling throughout the continent and meeting the respective heads of governments. It helped me get to know the continent better.

I realised that one of our weaknesses in South Africa was that we knew more about Europe and North America than we did about Africa. One thing was clear: many African countries had got their education systems right, whereas we had failed miserably.

Also noticeable was the relationship between good governance and development. In countries where there was transparency in this matter, where there was no corruption, development occurred for the benefit of the most vulnerable in society. At the time, even Zimbabwe was still working, but in the intervening years, I have watched with sadness as things fall apart there. That country is a lesson in how beneficiation can be derailed. It is indicative of Africa's underperformance, which diminishes the entire continent in the eyes of many elsewhere in the world.

Until Mbeki's HIV policies, South Africa was regarded as a country apart from the continent. And this would have continued, especially with the New Partnership for Africa's Development campaign, but when that was set against the denial of a disease that had the potential to destroy our country's future, we lost momentum. We lost respect. It was a more sombre country to which I returned, one certainly less buoyant than the one I had left at the end of the previous millennium.

I came back to South Africa to retire. I wanted to write, read and travel. In 2004, I was 57 and I felt that I had done what I needed to do in my life. So, throughout 2005, I wrote and read and stood in my lounge and looked at the sea. I was now doing what I most wanted to do. During this time, I wrote Laying Ghosts to Rest: Dilemmas of the Transformation in South Africa. I had time for reflection and the freedom to write.

Active citizenship

But then, slowly, South Africa came knocking. There were invitations to sit on various boards. My son Hlumelo, an entrepreneur, asked for my support. I became chair of his Circle Capital Ventures, a venture capital company that had invested in MediClinic and Eduloan.

This was preceded by an invitation to be a director on the MediClinic board, and after that came approaches from Standard Bank and Anglo. I agreed to both of these, but decided that would be my quota. I did not want to overburden myself because I still had this notion of having the space to read, write and travel.

I had returned from the World Bank with a much better idea of how the world economy worked – and failed to work – and I had experience of other countries and how they tackled problems similar to our own.

With this background, I had no intention of getting involved in government, but I did feel that it gave me a platform as an active citizen. Being an active citizen had been a constant refrain throughout my life and just because I wanted to retire did not mean that I would still that voice.

I felt that if I was to contribute to transformation in the country, one way was through the private sector and another was to support the government wherever there were good people doing good work. Hence my support of Naledi Pandor as minister of education and later science and technology, and Mosibudi Mangena, a friend and compatriot, as minister of science and technology.

It is axiomatic that the economic might of every country is in the hands of the private sector. Government is an enabler of a country's business, but for transformation to be meaningful, it has to occur where the country is shaped. Hence, my engagement with the likes of MediClinic, Standard Bank and Anglo American. If I could use my skills to change their domain, then I could help contribute to the sustainable development of the country.

Then, in 2007, I was approached by Old Mutual and Nedbank to chair another scenario-planning exercise. We had been through this before, in the early 1990s, but we needed new vision.

I saw an opportunity to explore, systematically, ways to get the government, the private sector and the non-governmental (NGO) sector to work together.

I saw it as a way to mend some things that had broken. For instance, the NGO sector in particular had been damaged by a government critical of its role. It needed to be reintegrated. One way of mobilising people for active citizenship was through NGOs, so revitalising this sector appealed to me.

My return to South Africa occurred during a time when President Mbeki was at his strongest. His belligerent attitude had struck terror into the hearts of many academics and commentators who were labelled as counter-revolutionaries the moment their public comment did not toe the party line. They were frowned upon as disloyal and many were cowed into silence.

I felt that this clampdown on freedom of speech had to be broken and, because I had nothing to lose, I felt it imperative to speak out.

Part of being an active citizen was about speaking up when the need arose. If something good occurred, you acknowledged it. But if something was wrong, and most of the time things were going in the wrong direction, then I believed it was important to say so.

I felt it was important to set the tone so that citizens believed they were entitled to comment on government failings. I did so. But I did so from the sidelines. At the time, I still had no intention of going into the rough and tumble of politics.

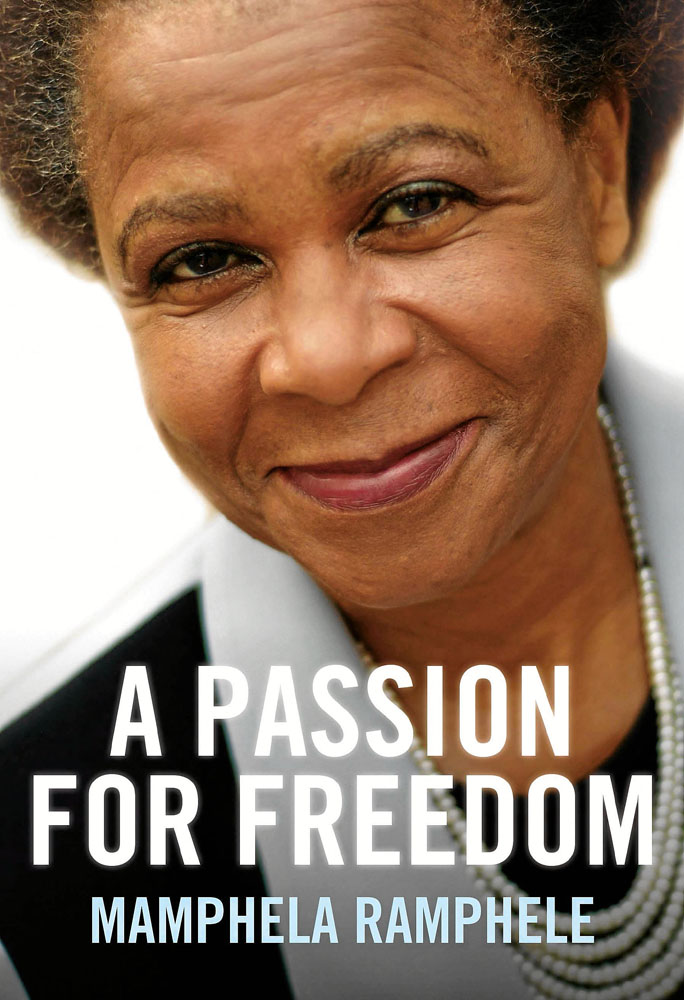

This is an edited excerpt from Mamphela Ramphele's autobiography, A Passion for Freedom, published by Tafelberg. The book will be in shops from November 14 2013.