Every year for the past three years the department of basic education has tried — unsuccessfully — to implement competency tests for matric markers.

Each year the teacher unions derail these well-intentioned plans, with the South African Democratic Teachers' Union (Sadtu) raising the biggest ruckus.

The department's logic is flawless: the integrity of the marking and moderation procedures of the National Senior Certificate exam depends crucially on the ability of markers to assess student responses accurately. Furthermore, without directly testing the content knowledge and marking competency of teachers one cannot be sure that the quality of matric markers is such that matric pupils receive the marks they deserve.

Importantly, the tests the department proposes would be conducted in a confidential, dignified and equitable manner that would not undermine the professionalism of applicants.

Sadtu counters that all teachers are equally capable of marking the matric exams and thus there is no need for minimum competency tests for prospective markers. This flies in the face of everything we know about teachers' content knowledge and the pedagogical skills of large parts of the South African education system.

In a 1999 book, Getting Learning Right, Penny Vinjevold and Nick Taylor summarised the results of 54 studies commissioned by the Joint Education Trust, and wrote: "The most definite point of convergence across the President's Education Initiative studies is the conclusion that teachers' poor conceptual knowledge of the subjects they are teaching is a fundamental constraint on the quality of teaching and learning activities, and consequently on the quality of learning outcomes." By implication this includes their ability to mark complex material accurately.

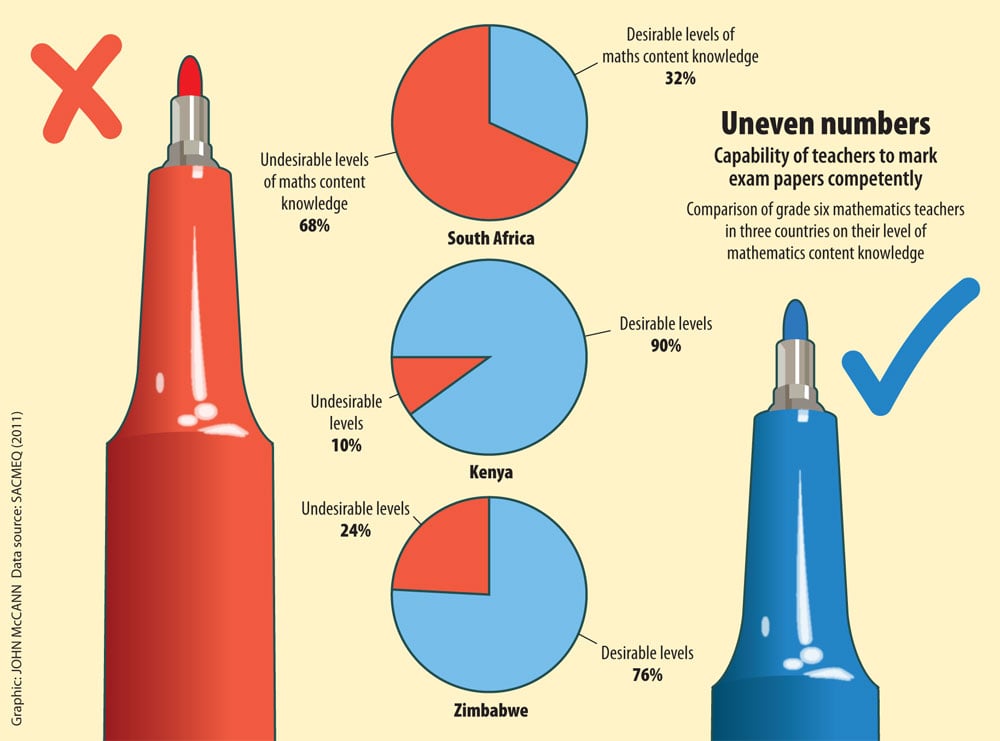

More recently, a 2011 report by the Southern and Eastern African Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality found that only 32% of grade six mathematics teachers in South Africa had desirable levels of mathematics content knowledge, compared with 90% in Kenya and 76% in Zimbabwe.

Similar findings

I could go on and mention the numerous provincial studies that have been conducted in the North West, the Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal and elsewhere that all find the same thing — extremely low levels of teacher content knowledge in the weakest parts of the schooling system — which, crucially, make up the majority of South Africa's schools.

Given this situation, one wonders how Sadtu can argue that all matric teachers are equally competent to mark the matric exams or that they should not be tested. The union stance is that a system of teacher testing will disadvantage teachers from poor schools who cannot compete with those from wealthier schools. Although it is certainly true that the department has failed to provide meaningful learning opportunities to teachers in these underperforming schools, jeopardising the marks of matric pupils to make this stand is misguided, unethical and potentially even illegal.

These are important but separate issues and should be dealt with in different forums. But it is worth noting that the Western Cape has been testing prospective matric markers in the province since 2011, the only province in the country to do so.

The logic of the unions on this matter is perplexing. On numerous occasions they have rightly argued that teachers in poorer schools have not had meaningful learning opportunities and, therefore, that teachers are unequally prepared to teach, and by implication also unequally prepared to mark. Yet now they are arguing that all matric teachers are equally capable of marking the matric exams? So which is it? You can't have it both ways. They either are or are not equally competent to mark matric exams. If it is the former, one cannot ensure children will receive the marks they are due; and if it is the latter, then one simply cannot argue that teachers should not be assessed prior to being appointed as markers.

On this question, a colleague of mine asked the following question: "How does the department employ people to teach matric when they are not considered competent to mark?" The uncomfortable answer is that, unfortunately, many matric teachers are neither competent to mark nor to teach — and this is because of no fault of their own. The blame instead falls squarely at the feet of the department, which has not provided them with quality professional development opportunities.

If one looks at the specifics of appointing matric markers, the union objections become even more bizarre. Although all matric teachers are legally allowed to apply to be matric markers, who is appointed and the criteria used for making these appointments are solely at the department's discretion. Provided that these criteria are aligned with the position and are not discriminatory on such grounds as race, gender and sexual orientation, the department can select whomever it decides is most capable of doing the job.

Selection criteria

Currently the selection criteria relate to qualifications, teaching experience and language proficiency, but — bizarrely — not content knowledge. Given the nature of the work — assessing student responses for grading purposes — it seems only logical that applicants should be able to demonstrate this competency prior to being appointed for possessing it.

Because of the importance of the matric exam's results for the life chances of individual pupils both in terms of further education opportunities and labour-market prospects, the department should put its foot down and take a stand for the 700 000 or so part-time and full-time students who are writing matric this year: it should insist that the 30 000-odd matric markers be tested prior to appointment.

Pupils, parents and school governing bodies have every reason to be concerned when there is no formal testing process to ensure that the teachers who will mark their all-important matric exams have the competence to do so in a consistent, fair and unbiased manner. Whether or not competency tests for matric markers are implemented has nothing to do with the unions and everything to do with the fairness of the marking and moderation procedures.

In sum, should prospective matric markers be tested prior to appointment? Yes. Is this a union issue? No. Will this be the last we hear of it? Unfortunately not.

Nic Spaull is a researcher in the economics department at Stellenbosch University. His education-focused research can be found at nicspaull.com/research. Follow him on Twitter @NicSpaull