THE GOLDFINCH by Donna Tartt (Little, Brown)

It is dangerous to write openings as compelling as Donna Tartt's. In The Secret History, the one-page prologue gives us a murder and a narrator who has helped to commit it. The Little Friend starts with the death of a child who, by page 15, is found hanging by a piece of rope from a tree branch, his red hair "the only thing about him that was the right colour any more".

And now, in The Goldfinch, Tartt has a 50-page two-part opening. In the first section, the narrator, Theo Decker, is holed up in an Amsterdam hotel, looking at newspapers written in Dutch, which he can't understand; he is searching for his name in articles illustrated with pictures of police cars and crime-scene tapes.

Before any of this is explained, the story moves back 14 years to the day Theo's mother dies, when he is on the cusp of adolescence. Her death takes place in New York's Metropolitan Museum, as a consequence of an exploding bomb – mother and son are in separate rooms when the bomb blast occurs, and the descriptions of Theo regaining consciousness in the wreckage, and trying to find his way out of the ripped-apart museum before returning home, expecting to find his mother there, are written in astonishingly gripping prose.

This is, of course, where the danger comes in: if, at the end of the kind of set piece to which the word "climactic" should emphatically apply, you still have 700 pages to go, aren't you setting your readers up for disappointment?

Astonishingly, the answer is no. The novel changes gear and, for a while, is primarily involved with showing us, affectingly, the dislocation of Theo's life – a dislocation both emotional and physical.

His mother dead, his father long absent, he finds himself living with the Barbours, the family of a school friend; this is understood by everyone to be a short-term option, and the cold spectre of unknown and unloving grandparents who will eventually become Theo's guardians hovers over the novel for a time until his father reappears, with his girlfriend, Xandra, and takes Theo off to live with him in Las Vegas.

Great Expectations

There will be more twists and turns in this tale of a motherless boy whose life involves dramatic changes and is peopled with a vast cast of characters, many of whose affections and intentions it isn't easy to work out. If there's any one novel this strand of the story calls to mind, it's Great Expectations – there's even a character called Pippa, perhaps a playful melding of Pip and Estella.

Pippa, near Theo in age, was also in the museum when the bomb exploded, and is the only person who Theo feels can understand his heart.

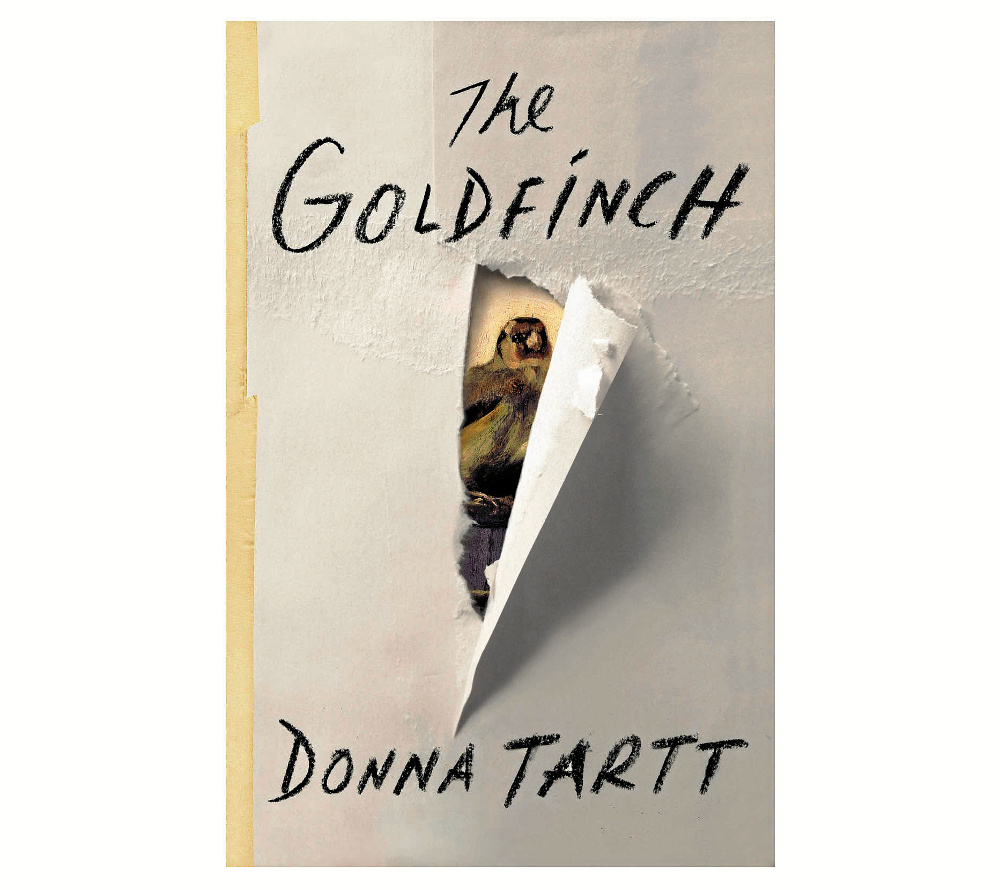

But there is a second strand to the novel, this one with echoes of Crime and Punishment. Young Theo Decker enters a museum with his mother; he leaves with a painting. The painting – one that actually exists in the world – is The Goldfinch by Carel Fabritius, a student of Rembrandt's, who died at the age of 32 when a gunpowder factory near his studio exploded.

Almost all his work was destroyed; The Goldfinch is widely considered the finest of the paintings that survived. "Anything we manage to save from history is a miracle," Theo's mother says to him, minutes before her death – an idea that runs deep in the veins of the novel.

Picking up the painting from the debris and walking out of the museum with it isn't exactly theft, not if theft involves the conscious decision to steal. Theo is acting in a state of mental distress, on the instructions of a dying man who tells him to take the painting.

This man, it so happens, is guardian to Pippa – at this point, she is nothing more to Theo than an arresting-looking girl, all too briefly glimpsed, though, later, their lives will collide and separate, repeatedly.

But once Theo reads in the newspaper that the painting is believed to have been destroyed in the explosion, he chooses to keep quiet about his possession of it – and from here on he is culpable.

As the years go on, both Theo's attachment to the painting (a thing of beauty, but also a physical connection to one of the last conversations he had with his mother) and his guilt over his continued possession of such a priceless work of art grows. So, too, does his fear of being imprisoned for stealing the object.

It should come as no surprise, in a novel that opens with crime-scene tapes and an exploding museum, that the story of Theo and the painting is a story of betrayal, suspicion, double-dealing and shoot-outs.

The Goldfinch

Raymond Chandler is no less a presence here than Dickens and Dostoyevsky. To say any more about the events of the novel would be to deprive a reader of the great joy of being swept up by the plot. If anyone has lost their love of storytelling, The Goldfinch should most certainly return it to them.

The novel isn't, of course, all action and suspense. Some of its most memorable moments occur in stillness. Take Theo's first experience of the desert skies of Las Vegas, after a life spent amid the light pollution of New York.

Until now, he has only known the constellations as "childhood patterns that had twinkled me to sleep from the glow-in-the-dark planetarium stars on my bedroom ceiling back in New York. Now, transfigured – cold and glorious like deities with their disguises flung off – it was as if they'd flown through the roof and into the sky to assume their true, celestial homes."

It is a glorious piece of prose, but placed within a novel about a boy who has lost his true home – which is, wherever his mother might be – it becomes heart-piercing, too. Tartt may already have displayed her great gift for plot in her debut, but the emotional register of The Goldfinch is of a different order from either of her previous works.

It would be wrong, however, to think that all the emotions are centred around loss. At the heart of the novel is an evocation of boyhood friendship – that of Theo and Boris, the Ukrainian outsider he meets on his first day of school in Las Vegas. Boris is an unforgettable creation – a thieving, drinking, drug-taking teenager who lights up each page he is on, even as he leads Theo into a world of excess. Their relationship works so well on the page in part because it has been prefigured by Theo's friendship, in New York, with a boy called Tom Cable – a friendship with a "wild, manic quality, something unhinged and hectic and a little perilous about it".

Tartt doesn't present Theo as someone who comes unmoored from his own character by the death of his mother, but, more convincingly, as a boy whose flaws become more deeply inscribed in him as a consequence of loss.

Then again, it is not entirely right to think of Theo's friendship with Boris as a flaw – the love between the boys is both simple and complicated, in the way of the best friendships. And when Boris re-enters Theo's life in adulthood it is impossible not to hope he is there as a friend, even while fearing the opposite.

Plot and character and fine prose can take you far – but a novel this good makes you want to go even further. The last few pages of the novel take all the serious, big, complicated ideas beneath the surface and hold them up to the light.

Not for Tartt the kind of clever riffs, halfway between stand-up comedy and op-ed columns, that are too commonly found in contemporary fiction. Instead, when plot comes to an end, she leads us to a place just beyond it – a place of meaning, or, as she refers to it, "a rainbow edge … where all art exists, and all magic. And … all love." – ?© Guardian News & Media 2013