Parents often exaggerate their praise of children with low self-esteem, hoping it will bolster their sense of self-worth. But a new study, recently published in the journal Psychological Science, has found that this inflated praise is actually doing more harm than good.

"Inflated praise can backfire with those kids who need it the most – kids with low self-esteem," says Eddie Brummelman, lead author of the paper That's not just beautiful – that's incredibly beautiful! and a doctoral candidate at Utrecht University in the Netherlands.

Johannesburg-based child psychologist Christine Scolari describes self-esteem issues as a common difficulty experienced by children.

"[They] don't like themselves, think they are worthless and have a lowered self-worth, think that everybody else is better than them. They are the children who don't want to try new things in case they fail," she writes on her website.

Inflated praise is different from simple praise because it uses excessive adverbs or adjectives. "You are good at that" is simple praise but "You are so very good at that" is inflated.

Praise classifications

In one of three studies that informed the paper, 114 parents (88% mothers) administered 12 mathematics exercises to their children – whose self-esteem levels had been determined beforehand – and then scored them, without the researchers present. These sessions were videotaped.

"Watching the videotape, the researchers counted how many times the parent praised their child, and classified the praise as inflated or non-inflated," according to a report by Ohio State University in the United States, where Brummelman was a visiting scholar.

About a quarter of praise given to the children was inflated, the research finds and, importantly, parents gave more inflated praise to children with low self-esteem.

"Parents seemed to think that the children with low self-esteem needed to get extra praise to make them feel better," said Brad Bushman, a communication and psychology professor at Ohio State and a co-author of the study.

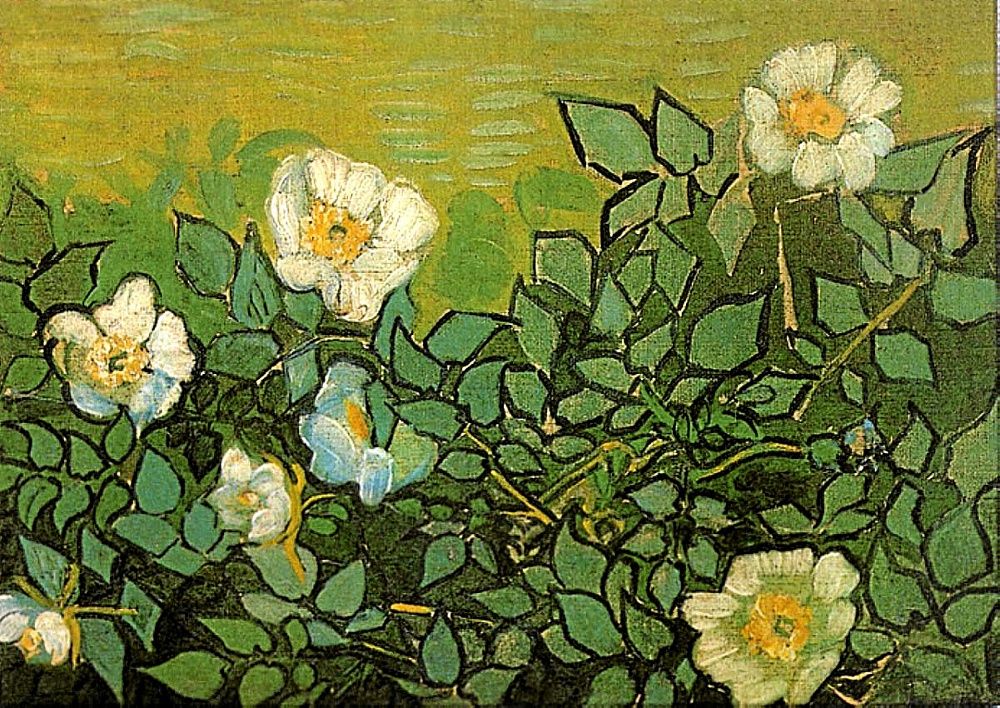

Vincent van Gogh's Wild Roses painting was used in a study to assess children's reactions to different levels of praise.

But another study by the same team showed that inflated praise backfired against children with low self-esteem, making them risk averse.

In the first step, 240 children were asked to draw Vincent van Gogh's Wild Roses painting, and were then given a note from a "professional painter" that gave either inflated, simple or no praise.

In the second, they were able to choose the next paintings to copy. There were two options: easy ones in which they were told "you won't learn much", or difficult ones in which "you might make mistakes, but you'll definitely learn a lot".

If they had received inflated praise in the first step, children with low self-esteem were more likely to choose an easy picture; on the other hand, after receiving inflated praise, children with high self-esteem were more likely to choose more difficult paintings.

Brummelman said: "If you tell a child with low self-esteem that they did incredibly well, they may think they always need to do incredibly well. They may worry about meeting those high standards and decide not to take on new challenges."

Bushman said that, although it may seem counterintuitive, parents should avoid giving children with low self-esteem inflated praise. "It really isn't helpful to give inflated praise to children who already feel bad about themselves."

Vincent van Gogh's Wild Roses painting was used in a study to assess children's reactions to different levels of praise. Photo: Madelene Cronjé