"I used to joke about being a Wall Street stockbroker, but I was never that way inclined. My father and two older brothers are artistic in various disciplines – visual and musical – but I was not born an artist," said Gabrielle Goliath.

An affinity for fashion led her to study fashion design at Wits Technikon (now the University of Johannesburg). And during the course of her studies her garments began to take a sculptural form, strongly informed by conceptual design with form being necessary in providing a visual cue.

This preoccupation naturally progressed to a desire to study art and, after completing her national diploma in fashion design, Goliath registered and eventually graduated with a master’s in fine art at the University of the Witwatersrand.

"I’ve always felt that art provides a valuable and critical vehicle for social commentary and creates necessary dialogue. As a South African female artist I feel a certain privilege and responsibility to deal with themes that speak to the experience of women in our country," she said.

"Whatever gesture you put out there as an artist should be a considered one and you should take full ownership of and responsibility for. My work to date has mostly dealt with the sociopolitical realm."

Goliath’s work has featured at the Dak’Art Biennial and Photoville, the Tierney Fellowship exhibition in New York in 2012. Last year she exhibited at Between the Lines at the former Tagesspiegel building in Berlin.

She is a recipient of the Tierney Fellowship award, the Brait-Everard Read award in 2007 and the Wits Martienssen prize. Her work is represented in the collections of the Iziko South African National Gallery and the Johannesburg Art Gallery, as well as in various academic, private and corporate collections.

Her portfolio includes a sound installation, Roulette (2012) – dealing with femicide; an installation, performance piece, Stumbling Block (2011), on the issue of homelessness; Berenice (2010), which explored violent crime; and Ek is ’n Kimberley Coloured (2007), on identity in South Africa. So it was inevitable that domestic violence became the subject of Goliath’s latest body of work, Faces of War, on at the Goodman Gallery.

Said Goliath: "It deals with the prevalent and distressing phenomenon of domestic violence. We know it’s out there – but by definition it’s confined to the domestic; it happens behind closed doors. So I’ve been trying to explore the idea of visualising the facelessness of it and articulate the silences around it. For so many complex reasons, it’s one that is not disclosed. Faces of War is a study of the portrait of this nature of violence."

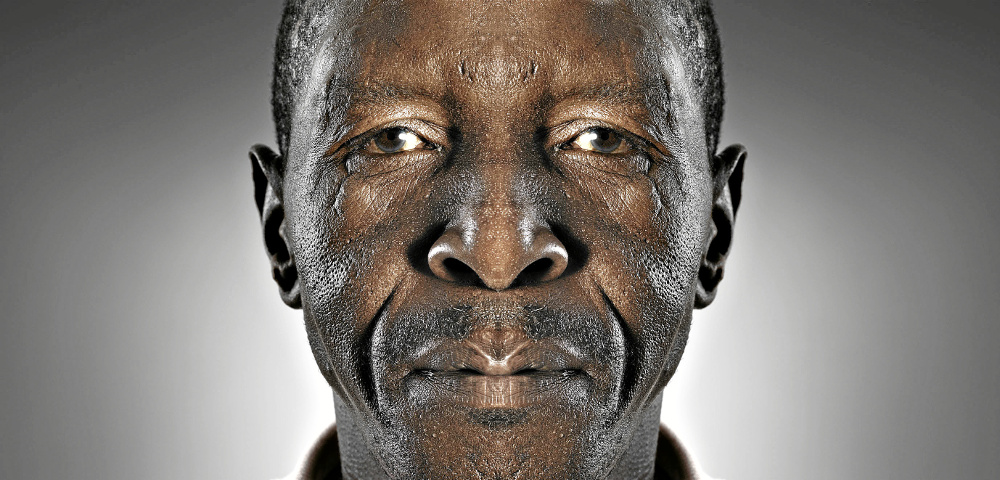

A series of 12 close-up portraits, photographed by Tony Meintjes, represents the faces of people who may or may not be victims or perpetrators of domestic violence.

Art from the Faces of War exhibition .Photograph by Tony Meintjes

Art from the Faces of War exhibition .Photograph by Tony Meintjes

The larger-than-life, extremely cropped, uniform images have formal visual impact. On closer inspection of the photographs, the weird symmetry of the faces becomes apparent. Goliath explains that only one side of the subjects’s faces was captured – and then reproduced and stitched together.

"I’m not undermining the physical abuse – but [am] looking beyond that."

Pencil sketches form the second part of the exhibition derived from recordings of women who courageously agreed to share their experience as victims of physical abuse.

Titled Personal Accounts, you only hear breathing in the videos – there are no voices relating grisly details. The process of extraction and editing – in essence censoring them – was intentional, in order to mirror the nature of domestic violence.

The third part comprises a series of small-scale etchings of the portraits from Krieg dem Kriege (War Against War), German pacifist Ernst Friedrich’s visual polemic depicting the true face of war with disturbing images of soldiers with their jaws blown off and parts of their faces missing. It was this book that fuelled her inspiration for this body of work.

In text titled Intimate Warfare, which is written by Alexandra Dodd, the critical thinking behind the collection is contextualised. The question posed is: How does one engage with the pain of others without inflicting further violence through representing the effects of that pain?

I had grappled with that very thought as I listened to Goliath explaining the process that brought the project to fruition. Yes, the interrogation of domestic violence is necessary. But how does one do that without feeling that one is again violating the victims for the purposes of conversation – or an exhibition?

The question unsettles Goliath, and she carefully and thoughtfully explained: "I was as considerate of my collaborators as possible. I worked with a social worker throughout the process. My aim was not to focus on the actual moment – the bruised eye, the cut lip, the graphic details – but rather my objective was to highlight that the victim or perpetrator could be anyone. Even someone you brush past when you’re walking down the street."

She approached people who are part of her everyday life – from the cleaner in her building to acquaintances – to pose for her.

Essentially, Goliath was asking them to lend their visible identities to put a face to domestic violence – to cast their faces boldly in that shadow of doubt – especially in light of the stigma that exists. "No one was glib about it. Some said no," she said. "And others didn’t hesitate."

Faces of War is on at the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg until February 15