Being part of the first intake at the brand-new University of Mpumalanga — the first the province can call its own — is as much a risk as it is an honour, students told the Mail & Guardian this week.

On Wednesday, 140 of these pioneering students attended their first lectures at the institution. Getting to this point has cost the national treasury R2-billion, the department of higher education and training said.

Another R8-billion is budgeted for the next decade, to grow the institution into one with about 18 000 students. Mpumalanga and the Northern Cape, which opened its Sol Plaatje University this week, are the only provinces that have never had universities.

Mzwakhe Nkosi, a bachelor of agriculture student, said if the university "fails then we will say it was a risk we all took. But if it survives then it is an honour to be one of the first students."

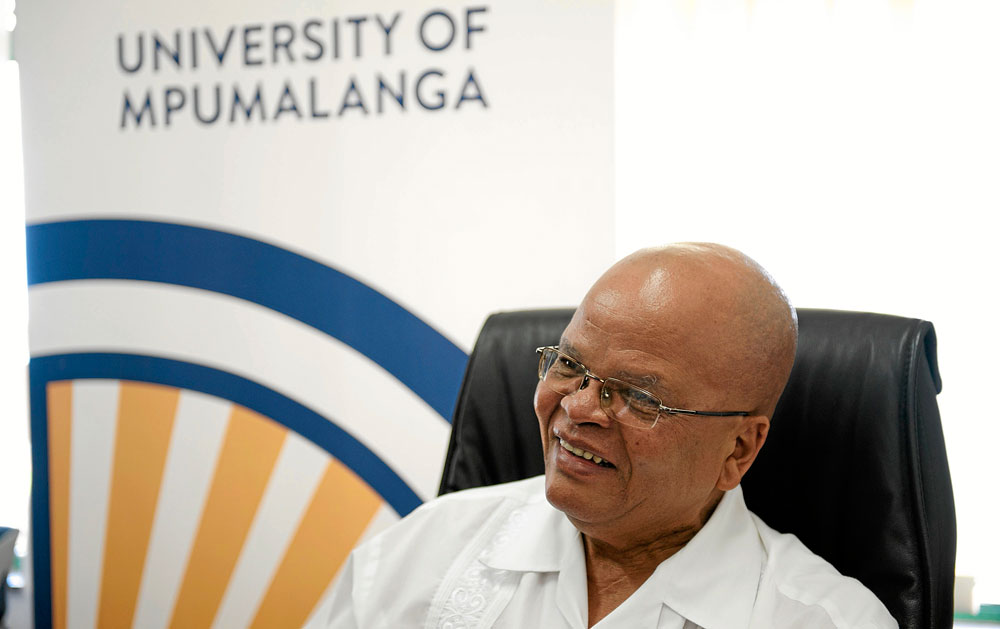

Acting vice-chancellor Andy Mogotlane said getting to the point of a university finally opening its doors, after two years of planning, is a proud achievement, but one that comes with its own pitfalls and problems.

Acting vice-chancellor of the University of Mpumalanga Professor Andy Mogotlane. (Madelene Cronjé, MG)

This planning included the department's negotiating for two established institutions to be incorporated into the fledgling university. These are the Lowveld College of Agriculture in Nelspruit and the education college in Siyabuswa, 330km away. The department also negotiated for hospitality students to have temporary use of the facilities at the Mpumalanga Regional Training Trust hospitality school in Kwa-Nyamazane, a short distance from Nelspruit, until they are moved to the main campus in a few years time.

First-year students such as Sibusiso Sibiya, who is studying for a diploma in hospitality management, "don't know what to expect".

"No one does. It's a new university, so no one's parents or friends can tell you 'this is what this university is like'."

But, Nkosi said, "we are part of history … I just hope that what is in the course is right, and the university will be managed right."

Standing outside the hall of the agriculture college, he and four of his peers spoke excitedly about their decision to study here.

Not having expectations means this first intake gets "to set the standard … and get straight As!" said Balungile Landzela, also a hospitality student.

Three courses are now offered: bachelor's degrees in agriculture and education, and a diploma in hospitality management. The university aims to offer a full complement of degrees and diplomas within 10 years, Mogotlane said.

Both universities will each year save hundreds of school-leavers the financial and logistical burden of being forced to pursue degrees and diplomas in other parts of the country.

Sibiya said not having to pay for transport and living costs was a "financial relief". "We're not all loaded out there on the farms where we come from."

All the students the M&G spoke to are Mpumalanga locals. They talked to one another in excitement, their confident voices carrying over the din of other students making their way to lunch.

That was on Monday, the first of a two-day orientation. The students had just learned about discipline on campus.

Venetia Mgiba, an agriculture student, said having a university "right here" in the province meant some students could "stay with their parents while studying.

"It's hard to travel to Johannesburg or Limpopo and places like that to study."

On Wednesday the deputy minister of higher education and training, Mduduzi Manana, told the M&G that there "are of course risk factors" in opening a new university.

"The big elephant in the room is … [being able to] recruit academics who are sceptical about coming here. But we have bold academics who have agreed [to join the university]," he said.

Deputy Minister of Higher Education and Training Mduduzi Manana. (Madelene Cronjé)

Mogotlane said the academic staff already recruited "could make you weep with pride" because "they have shown a pioneering attitude coming here, and a missionary's zeal".

Students need not have doubts over the credibility of courses or the functioning of the university, he said. "There are teething problems, for sure, as you would expect for a new university … but I think we are handling them well."

The university still needed to fill some academic positions, he pointed out. All three campuses had old residences, which needed fixing. This had already pushed back the opening date by a week but students were in their residences this week, albeit "some with cold showers".

He excuses himself and answers his ringing landline phone. "What is my direct line in the office?" he asks the person on the other side. "I have no idea."

As far as course content goes, "that is not a concern".

"All the courses will fall under the patronage of established universities like the University of Pretoria and the University of KwaZulu-Natal, who will do quality assessment and enhancement of our courses for an agreed-upon number of years."

Although students associate skills and jobs with the new university, some Nelspruit business owners see dollar signs — cautious dollar signs.

Coenraad van den Burgh, the owner of Shooters pool hall and pub, said an influx of students "could make us a lot of money", "but this is the 'Slowveld': it takes a long time for things to get going".

Cornelle Crowley, chief executive of the Wimpy in Nelspruit's Riverside Mall, the closest shopping centre to the university, said "it could be good for business — but I wonder if the university will organise transport for the students to get here?"

For now, though, the eyes of Nkosi and his peers are set on the opportunities that come with getting a solid education.

He wants to have his own farm someday. Studying agriculture will allow him to do it "the right way".

"I want to be an example to young people to say 'you study, you work hard, you do things properly'," he said proudly.