Full house: Increasing student numbers at the University of Johannesburg and others

The first-year psychology class at the University of Johannesburg (UJ) was so big last year, some students had to sit on the floor.

"There were more than 600 students at my [first year] psychology lectures last year, and the venue wasn't big enough," said Vusi Zwane (21), a second-year BComm student majoring in industrial psychology.

The biggest problem with not having enough lecturers is the loss of interaction during lectures, he said.

"Someone would raise their hand on one side of the venue, and you wouldn't hear what they were saying. That isn't right because this is the kind of subject you need to discuss and debate," he said.

Although his second-year classes are smaller, Zwane said he had to queue to use the computer laboratory and the library was often too full to find a desk to study at, "so we sit outside and try to read, even while it rains. We would get a higher quality education if there were more lecturers and smaller classes."

University of Johannesburg student, Vusi Zwane. (Madelene Cronje, MG)

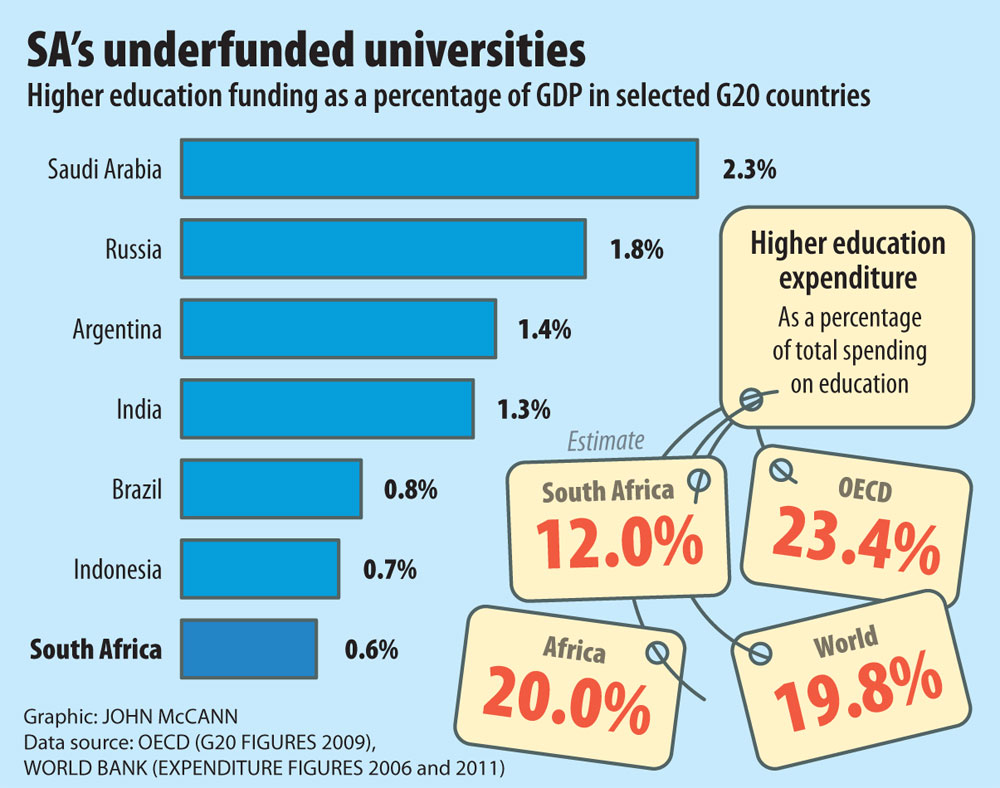

According to a report by the higher education and training department, South Africa's universities are severely underfunded by the state. They have also not met government targets set more than a decade ago.

Commissioned by Higher Education Minister Blade Nzimande, the ministerial report said that in South Africa the funding of higher education "does not compare favourably with that of fellow middle-income countries such as Botswana, Chile, Hungary or Mauritius".

In fact, South Africa lags behind the rest of Africa in this respect. "Higher education expenditure as a percentage of education expenditure for Africa was 20%," the report said. "[In] South Africa, [it] was about 12%."

The committee tasked with drawing up the report, chaired by ANC Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa, reviewed the "experiences of the past six years of … implementation of the current funding framework for universities". It used the goals set for the sector by, among others, the 2001 national plan for higher education, as a yardstick.

Although student numbers continue to grow, the numbers of those teaching them remain largely the same because universities don't have the funds to hire more lecturers.

Arnold Wentzel is a lecturer in the education faculty at the University of Johannesburg. Until this year, he was a lecturer in the economics department with classes of up to 600.

"Think about the administration that comes with this. When you set tests, sometimes you end up with thousands of scripts to mark," he said. "With those numbers, it's impossible to give every student detailed feedback, which takes away from the learning experience.

"Sometimes there aren't enough seats for everyone, so students end up not coming to class. I've seen lectures happening in corridors because there aren't enough venues.

"I didn't know my students' names, there were so many of them … I didn't even recognise their faces. It's toughest on the students."

University of Johannesburg lecturer, Arnold Wentzel. (Madelene Cronje, MG)

The wide-ranging 411-page report said the higher education system remained "very inefficient, performing way below most of the targets set".

"Participation rates of African and coloured students remain below 15% compared to those of students from the white and Indian population groups [59% and 46% respectively]," Ramaphosa said in his introduction to the report.

"Our university system is largely an undergraduate system, with master's and doctoral enrolments constituting only about 6% of total enrolments.About 50% of students who enrol in our universities drop out before graduation."

The report said that, because of "inadequate" state expenditure, working conditions within higher education "show signs of deterioration as a result of increasing student-to-academic staff ratios".

The chief executive of Higher Education South Africa, Jeffrey Mabelebele, claims the sector is in "crisis" because of the negative effect of high student-to-lecturer ratios on research output and infrastructure, as well as general underfunding, among other problems.

"In light of the projected 25% growth in the sector, and if we are going to be able to get ourselves out of this precarious situation, then the state is going to have to put some extraordinary measures in place," he said.

Ian Scott, emeritus professor at the centre for higher education development at the University of Cape Town, estimates it would cost the sector between R700-million and R1-billion a year — about an extra 15% in current staffing costs — to hire the additional lecturers needed for more effective staff-to-student ratios at present enrolment levels.

"This is not impossible if you look at the kind of funding injections happening in other areas like the National Student Financial Aid Scheme [NSFAS]," he said. "Making an investment like this would mean better quality teaching and learning, more students finishing their degrees, and less money lost on students who don't."

In its list of recommendations, the report said the government should increase the funding for higher education "to be more in line with international levels of expenditure".

It also said that "high levels of inefficiency", along with "corruption and mismanagement of funds", would first need to be addressed "for additional funding to have any meaningful impact".

The committee recommended that the way grants for research are awarded — a source of bitter controversy among many academics — should also be changed.

"The funding framework must be adapted to actively reward excellence and quality, not only quantity.

"One way would be to follow international practice, whereby existing accredited journals are rated or ranked in terms of criteria such as citation impact."

According to the report, Nzimande should consider introducing an "institutional factor grant" for historically disadvantaged universities. This would take into account the extensive challenges such institutions face, such as their rural location, large student numbers, inadequate resources and underprepared students.

Underfunding has also hit NSFAS hard. Although the scheme's budget has increased substantially over the past few years, this has been "negated by student fee increases that have, in some instances, been higher than inflation, and in a number of universities there have been double-digit increases," Nzimande said in the foreword to the report.

Capping fees "is an area that I believe requires further attention", he said. Student protests erupted at 11 campuses at the beginning of this year over a shortage of financial aid and students being denied admission to universities.

But the report does not back Nzimande's recommendation, as it states unequivocally that the capping of fees should not be implemented.

"The quality of higher education would suffer, and universities would not be in a position to cross-subsidise other financially needy students through university-funded student bursaries," the report said.

The deputy vice-chancellor of UJ, Angina Parekh, said the university had already set aside R20-million "for additional teaching resources in the form of tutors, senior tutors and assistant lecturers" to try to alleviate the challenge of damaging staff to student ratios.

But the demands on the university's funds in other areas such as NSFAS supplementation did not make it sustainable for the university to continually use its own funds for additional teaching resources, she said.