The Zimbabwe Stock Exchange (ZSE), one of the few remaining bourses in the world that still operates a manual trading system, will this year graduate to an automated one. The Central African Stock Exchanges Case Handbook, 2010, explains that the ZSE "uses a call-over system on the floor of the exchange" and "conducts one call-over session daily between 10am and noon".

It is a modest institution, housed on the fourth floor of the Union Avenue Building in Harare. Trading takes place in a rectangular room around a high oval table. Since 2006, the daily trades have appeared on an electronic screen at the far end of the room, but this is merely an electronic representation of what is happening manually, the information fed into a computer by a person sitting in the corner of the room.

The ZSE signed a contract with Infotech Middle East on March 19 to install the automated trading system.

According to Martin Matanda, one of the automation project's key drivers, the ZSE has remained time-locked owing to a domestic scarcity of foreign exchange in recent years, and to the fact that major multilateral lending institutions that assisted other regional exchanges' transition to automation closed their doors to Zimbabwe in the 1990s and early 2000s. This happened partly because the Zimbabwean government was in breach of existing loan agreements and partly in reaction to the government's policies of economic nationalisation.

The automation project, which will cost about $2-million, has been initiated in a decidedly stagnant period for the local bourse. Between June 2013 and March 2014, the equities market lost more than $1-billion in value, dropping from $5.96-billion to $4.8-billion.

Liquidity crisis

This fall has occurred within the wider context of a liquidity crisis that is popularly ascribed to the Zimbabwean government's policies of economic nationalisation, especially the launch of the fast track land reform programme in 2001 and the signing into law on March 9 2009 of the Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Bill, which legislates 51% indigenous ownership of all foreign-owned businesses in the country.

The chaotic implementation of the former policy destroyed the agricultural sector, and the uneven and opaque application of the indigenisation Act has discouraged investment in the mining sector in particular.

The local manufacturing sector is also in a state of collapse, in no small part because a loss of foreign investment has left Zimbabwean banks unable to offer long-term loans.

These hardships are reflected by a slew of stock market delistings and suspensions in 2013 and 2014, including one-time economic mainstays such as Cairns, Caps Holdings, Chemco, Steelnet and Interfresh. There has not been a new listing on the ZSE since 2009.

According to economist John Robertson, there have been some rights issues but these have been to raise money to pay off debts.

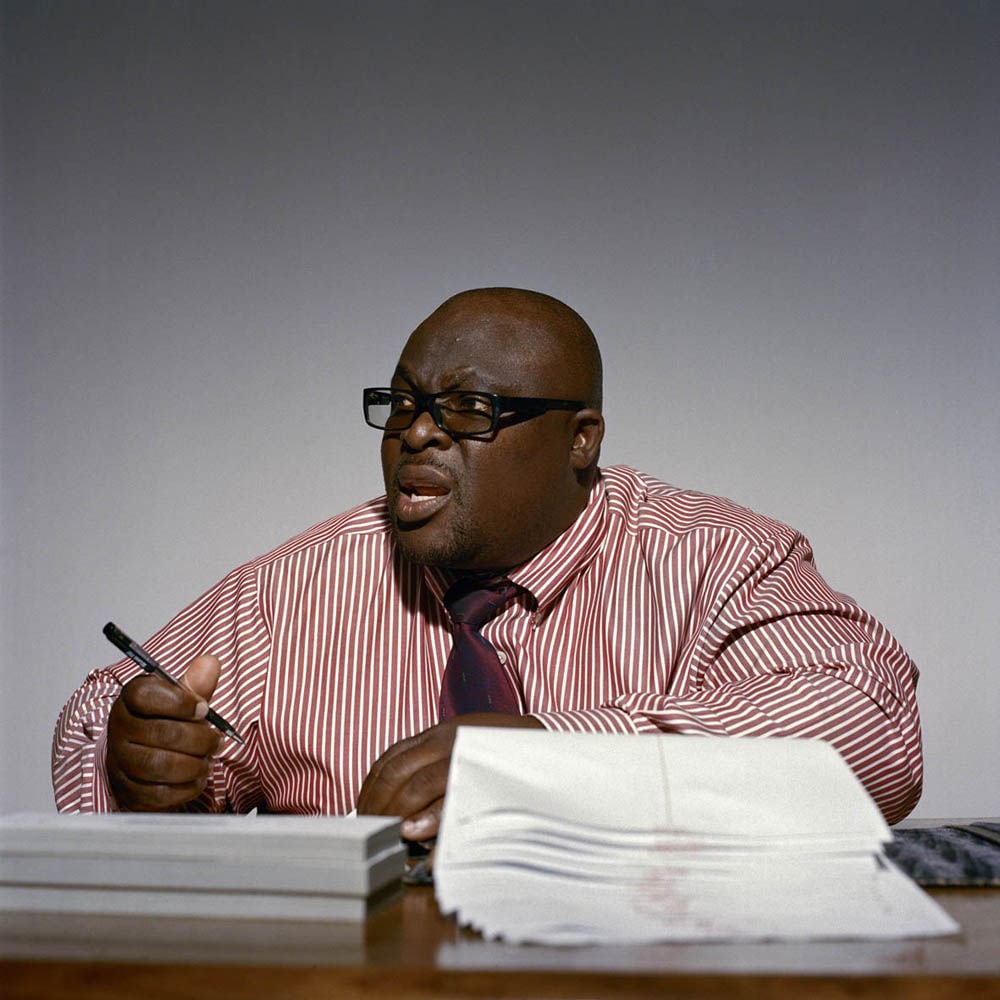

Wellington Mapedzamombe is a trader with ZB Securities, at the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange

As dire as the economic situation in Zimbabwe is, the ZSE has survived worse. "If there is one thing that is truly remarkable about the ZSE, it is the fact that it survived the hyperinflationary period between May 2002 and February 2009 more or less intact, as it remained capitalised in hard currency terms at around $4-billion throughout the period, which is pretty much where we are now," said Jono Waters, publisher of the Central African Stock Exchanges Case Handbook.

According to Robertson, "share transfers and share sales were a large part of the economic activity in the country during the hyperinflationary period, mainly because of the fungibility or transferability of shares – the fact that companies listed on more than one stock exchange were allowed to move a portion of their shares to other markets."

A company such as Old Mutual, listed on the ZSE, the London Stock Exchange and the JSE, would be selling shares on all three markets on the same day, enabling the ZSE to work out a truer value for the Zimbabwean dollar in sterling and rands than was reflected by the many other exchange rates in existence at the time.

Harare's stockbrokers remember this difficult period all too well.

"When inflation began to gallop, Zimbabweans looked to the equities market as a way of protecting the value of their money. Buying shares was an attractive option for many people because our regulations meant that we still had to accept cheques when nobody else in Zimbabwe would have dreamt of doing so," said Thandiwe Shonhiwa, a stockbroker with Southern Trust Securities.

Foreign influence

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the buying and selling of shares on the ZSE had increasingly been led by foreign institutional investors, which had identified Zimbabwe as the future gateway to central Africa.

But with the Zimbabwean economy in freefall in 2006, the investors were suddenly all domestic – individuals and local institutions, desperate to immunise their cash from radical devaluation.

"What tended to happen is Zimbabweans would be sent forex by relatives and friends living outside the country, and this would be changed into millions and later billions of Zimbabwean dollars and the currency dealer would then write a cheque for the amount and hand it to us, or deposit it in our account.

"On the one hand, we as brokerages were abused during this time, because we had no way of getting this money out of the bank but, on the other, these low-liquidity investors enabled us to keep our doors open," Shonhiwa said.

Brokerages popped up all over the city – there were 23 at the height of hyperinflation.

The Zimbabwe Stock Exchange

"It changed the character of the ZSE because, whereas before trading had tended to be fairly sedate, there were now more brokers than there was seating room. The table was raised and trading was henceforth conducted standing up, a situation that persists today. As brokers, we were also changed. Everyone knew their 75 times table. We all carried calculators that ran to 25 zeros and, when it came to buying, we didn't discriminate: demand outstripped the availability of shares to such an extent that you bought whatever you could, and trading was often done within half an hour," Sebastian Gumbo, a stockbroker with Imara, said.

Eventually the entire financial system became completely overwhelmed, and trading in the local currency in effect ceased on November 17 2008 owing to issues over settlement after the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe introduced several new measures.

A political partnership between Zanu-PF and the Movement for Democratic Change resulted in the dumping of the Zimbabwe dollar in favour of a multi-currency system anchored by the United States dollar. Trading in US dollars began on February 19 2009.

"Initially trading was sluggish because nobody was sure of the dollar value of stocks and very few local institutions had any money. Essentially it was the behaviour of returning foreign investors, many of them South African fund managers, that demonstrated which shares were undervalued and which were too pricey. If there was a rush for certain shares, you knew they were undervalued," said Chris Masendeke, head of trading at EFE Securities.

Since dollarisation, activity on the ZSE has been dominated by foreign investors, mainly pension, insurance and medical aid fund managers.

Curious developments

"It's a curious set of developments really because very few of the shares listed on the ZSE are paying dividends. Most of them are being bought and sold because people believe there are capital appreciation prospects when things come right. That's what everybody's looking at.

"In plain speak, people feel that, when Robert Mugabe goes, all kinds of things will change, and the value of companies that are currently almost valueless will immediately rise," Robertson said.

One of Lisa King's visual studies of the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange

In the meantime, life remains difficult for the 12 local brokerages active on the ZSE, which do $477-million in trades annually and share a mere $9-million in revenues, with most of this money going to the three biggest brokerages – Imara, IH Securities and Murray Lynton-Edwards.

"We are operating in a near-deflationary environment, where the only way to keep our heads above water as a business may be to cut costs – retrench staff, downsize premises, etcetera. Ironically, it is likely that the automated system will initially lead to more staff cuts, because it will reduce back-office work," Gumbo said.

But the ZSE chief executive Alban Chirume said that, when automated trading goes live in the second half of the year, it is hoped it will treble daily turnover on the exchange and, at the same time, reduce losses to brokerages caused by criminal exploitation of the weak manual system.

The images in this article are by Lisa King, who began photographing the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange in 2011. Her project is a visual study of the space, and a portrait of the people who participate in this rare form of exchange. Fourthwall Books will publish a book of her work in mid-2014. All photographs © Lisa King.