Amcu's basic pay demand remains at R12 500 a month.

As the longest strike in South Africa's history continues on the troubled platinum belt, it may have presented Anglo American Platinum (Amplats) with an opportunity to finish what it started last year and retrench a further 25 000 employees at its Rustenburg operations – half its workforce.

Amplats began to show signs of stress this week when sending notices about its "inability to fulfil a contract due to unforeseeable circumstances" to a number of its Rustenburg suppliers.

Company chief executive Chris Griffith last week told the media that the company is looking at different scenarios for when it would have to "shut down Rustenburg".

Although striking workers appear resolute, corporate investors are too. Amplats' share price is in fact higher than it has been over the past year, which suggests the market expects the company to come out of the dispute in a healthier state.

Government squared up to Amplats last year when the company announced plans to close four Rustenburg shafts, putting 13 000 jobs on the line. Mineral Resources Minister Susan Shabangu's response to the announcement was read as a threat to withdraw the company's mineral rights.

Amplats compromised; three shafts were placed on care and maintenance and 7 500 jobs were lost.

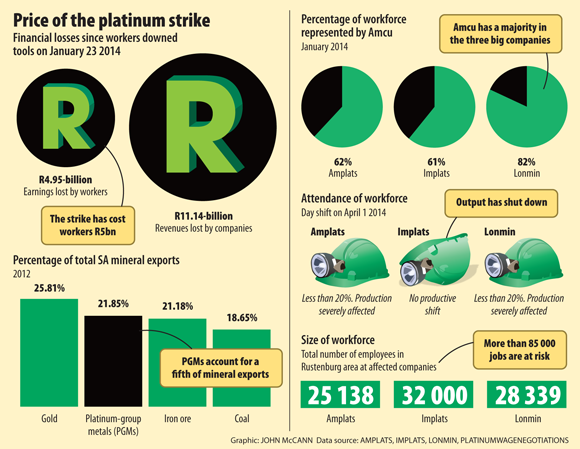

The strike, led by the Association on Mineworkers and Construction Union (Amcu), began on January 23 but a compromise has not yet been reached.

Amcu president Joseph Mathunjwa said all the platinum companies would retrench regardless of a strike, and had threatened retrenchment to break the strike.

"If capital does have financial and economic pressure, why don't we hear Chris Griffith reduce his salary from R6-million to R1-million per annum? They have even made [an] undertaking to shareholders to increase profits. Why must these trying times be felt by the workers?"

Industry experts agree that closing shafts has become an increasingly attractive option for the company. This is even likely to satisfy corporate investors because Rustenburg operations remain a profit concern.

The platinum producers have also threatened to mechanise operations because "every day it's looking like it makes more sense", said Peter Major, mining analyst at Cadiz Corporate Solutions.

But only a small number of South Africa's platinum group metal ore bodies are suitable for mechanisation. Major said companies would likely close narrow reef mines, of which there are many, rather than mechanising them. Once closed, "it is virtually impossible to open a deep-level shaft again", he said.

But there are political complications and legal considerations.

"I think it's not going to be easy for them to execute regardless of timing. I'm sure government will get involved again as they did previously," said Michael Kavanagh, mining analyst at Noah Capital.

Options to break such a strike are limited because the law only allows for the dismissal of employees who embark on a protected strike for reasons that relate to the employer's operational requirements.

"This means you can retrench," said Hugo Pienaar, a director in the Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr employment practice. "But if you want to follow that procedure, you must consult first for 60 days and give 30 days' notice of retrenchment." Currently in Rustenburg, “the formal process to be followed prior to retrenchment is impractical and may be impossible”.

The most costly part of closing down a mine is thought to be paying out employees.

But "if an employee unreasonably refuses to accept an employer’s offer of alternative employment, the employee is not necessarily entitled to severance pay", Pienaar said.

In this case, the current wage offer on the table could be considered a reasonable alternative offer.

Despite the enduring nature of the strike, the platinum price has remained subdued: at about $1 450 an ounce, it is at the same level as when the strike began.

The answer, some believe, may simply be that there is too much supply in the system.

"The industry has oversupplied the market for a number of years since the global financial crisis and inventories have been building up over the years," said Grant Sporre, Deutsche Bank's commodity strategist.

Stockpiles

It is highly likely these stockpiles have been built up by both the producers and the auto industry, he said.

According to Major, almost all metal prices have been falling over the past few years – reverting towards their median price. The average real price of platinum since 1940 has been $940 an ounce, so he believes $1 400 is unsustainably high and is being supported by the protracted labour action.

Exchange trade funds, which hold 2.5-million ounces in platinum, are also a holding that were never as prominent before. South Africa's mines supplied about 4.1-million ounces to the market in 2013.

Company share prices have also been surprising. Anglo Platinum's share price is stronger than it has been in a year at R500 a share and Impala Platinum's share price has held fairly steady over the length of the strike at around R120 a share. Lonmin's share price, at R50 a unit, has declined from R60 earlier this year.

"The share prices, particularly Anglo Platinum's, are overdone, especially if you compare the company potential to deliver cash flow and dividends," said Kavanagh. "It seems the logic the market is following is that this strike will ultimately result in higher US dollar metal prices, and a weaker rand, resulting in higher profitability."

Both Amplats and Impala have other operations besides Rustenburg, and even in Zimbabwe, which are unaffected by the strike. Lonmin, with no production, is the worst off and this week it asked non-striking employees to take leave to reduce costs and reserve cash for the company.

Amcu's basic pay demand remains at R12 500 a month. The proposed company increases would take the minimum wage to between R6 300 and R7 200 by 2015, excluding benefits and bonuses.

Mathunjwa said the union has agreed for the increase to R12 500 to be spread over four years, describing it as "a breather" for the companies.