Going up: The Reserve Bank reports that the current account deficit for the fourth quarter of 2012 was higher than expected.

With tapering being the watchword in financial markets everywhere, there is growing scrutiny of how central bankers communicate monetary policy decisions.

The South African Reserve Bank is not immune to this pressure, including questions over whether it should supply “forward guidance” – clear indications to the market about the direction of interest rates – increase the transparency of its monetary policy committee (MPC) meetings and reveal the voting records of its members, which would separate out the montetary policy hawks from the doves.

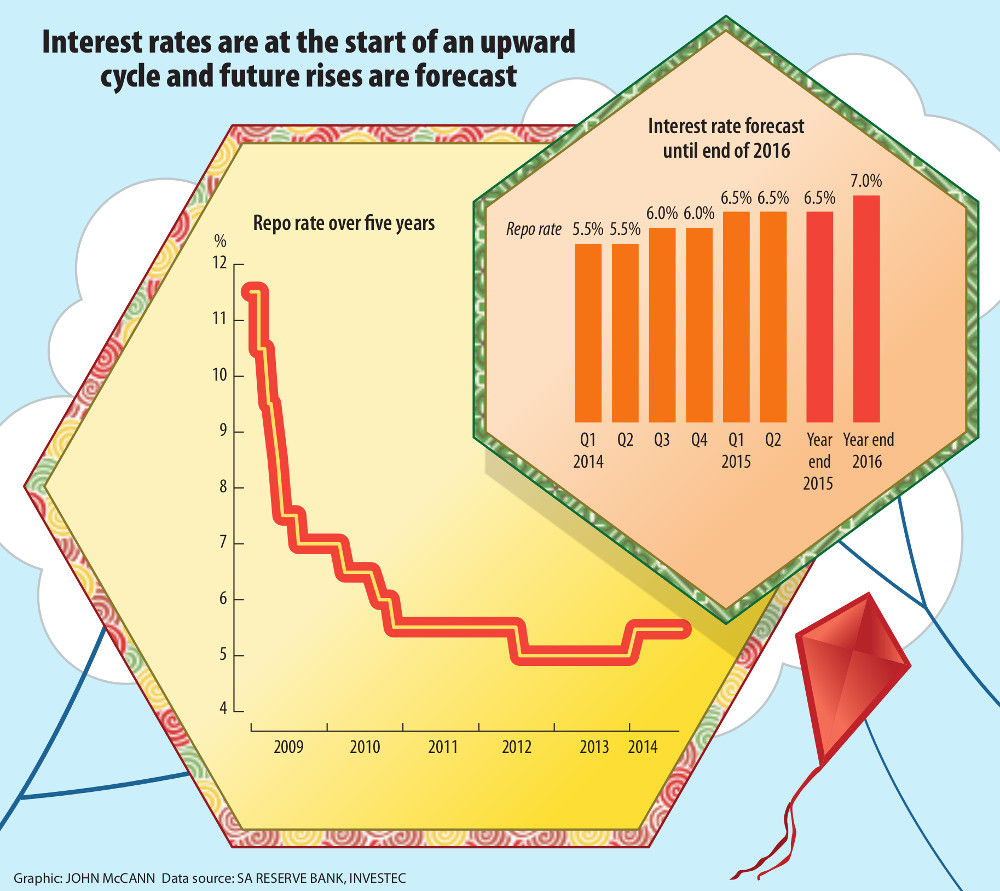

This week, the MPC left the repo rate unchanged, as the market had expected, at 5.5%, with five members in favour of holding rates and two in favour of raising them. This was not the case in January, however, when it raised rates, catching most if not all market observers by surprise, despite what the bank argued were many signals that it may have to begin hiking rates.

Despite this hiccup, most analysts and economists agree that the Reserve Bank’s communication is steadily evolving and improving, even if it does not follow the tradition of other central banks, such as the United States Federal Reserve, which publishes detailed minutes of its meetings and voting records.

Nor does it provide explicit forward guidance to the market, despite clearer indications in recent MPC statements that real policy rates are likely to increase in the medium term – but with the important caveats that this is “data dependent”, that “there will not necessarily be a change in the stance at every meeting” and that the increments may vary in size.

Differing views

In a recent research note, Nomura analyst Peter Attard Montalto noted that the bank has taken a significant step in admitting that MPC members have differing views and that the split does affect the balance and outcome of policy.

Following March’s MPC statement, for instance, the Reserve Bank governor, Gill Marcus, revealed how close the vote was, when asked about it – four members had voted to keep rates unchanged and three had voted to raise them.

But, according to Attard Montalto, the bank is unlikely to say more than that there were dissenting views.

Nevertheless, Nomura has drafted a spectrum of South Africa’s seven MPC members, ranging from hawks to doves. But it insists this is relative and will be fluid over time. But it does attempt to reflect the approach members may take at each meeting and the kinds of “concerns and focuses they will bring to the debate”.

On Nomura’s scale, ahead of Thursday’s meeting, deputy governors Daniel Mminele and Lesetja Kganyago were at the hawk end; Kuben Naidoo was neutral; Marcus and the third deputy, Francois Groepe, are neutral–leaning doves; and Brian Kahn and Rashad Cassim are deemed doves.

Confidential voting

The bank does not reveal how they vote, given the risk of the politicising their decisions.

Nedbank economist Dennis Dykes said it was not inconceivable that MPC members could have protests outside their doors for voting to raise the repo rate.

Marcus said in a recent speech that the bank does not publicise individual votes as it does not want to “personalise the debate”.

“This gives individual members greater freedom to speak their minds and change their views during discussions, and it avoids the labelling of hawks and doves,” she said.

“However, we do indicate if there were dissenting views but we do not reveal who the dissenters were. It does reduce the transparency of the decision-making process but this has to be weighed up against the advantages of allowing for more rigorous debate in the [monetary policy] committee.”

‘Committee responsibility’

To ensure the clarity and consistency of its message, the bank has adopted the principle of “committee responsibility”.

“So, even if the decision is not unanimous, once the decision is taken, all members of the committee take joint responsibility,” she said.

“This reduces the possibility of mixing the messages, as all members communicate with one voice.”

Tied to this debate is the question of forward guidance, particularly given the current reduction of quantitative easing in the developed world, which has required central banks to be more careful in their communications to prevent painful market volatility following a policy pronouncement.

The Standard Bank’s group chief economist, Goolam Ballim, said “good central banking provides guidance to the market that douses current and prospective volatility in the yield curve to maximum effect”, ideally giving the market a sense of where the price of money will be over time to allow for prudent business and investment decisions.

Best guidance

Nevertheless, he said, although the Reserve Bank may provide its best guidance on how it thinks monetary policy will unfold, unforeseen events may occur. In this respect, forward guidance “is inherently prone to miscalculation”, Ballim said.

This is particularly the case for South Africa, according to Sanlam Investment economist Arthur Kamp, given the openness of the economy, the volatility of the currency and the impact commodities have on inflation numbers.

The Reserve Bank itself appears to have mixed feelings on the matter. In her speech Marcus said that there was “by no means universal acceptance of some of the recent developments globally, and there are criticisms that, at times, forward guidance has introduced more volatility into the markets, and that too much guidance can encourage excessive risk-taking and delay monetary policy responses”.

It is “more difficult in emerging market economies that are more prone to volatility arising from exogenous shocks and spillover effects” she said.