Emissions from the Kendal power station have affected at least 124 000 people.

Air pollution caused by Eskom’s coal power stations in two provinces is killing at least 20 people a year and could jump to 617, with 25 000 people hospitalised, once all its stations are up and running.

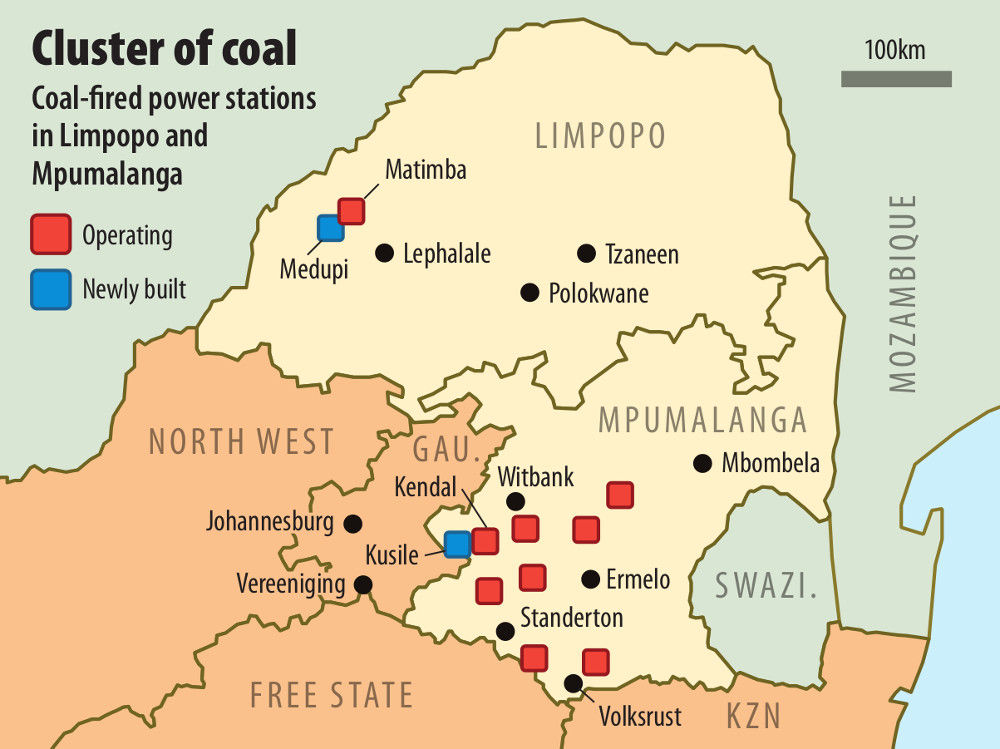

These would include the giant Medupi and Kusile power stations in Mpumalanga and Limpopo.

This disclosure, contained in Eskom-commissioned reports that have been released following an application from an environmental rights organisation, comes in the week in which President Jacob Zuma announced a shake-up of the energy sector.

He said in his State of the Nation address on Tuesday that the construction of Medupi will be accelerated and that the government is committed to building a third mega coal power station.

With South Africa facing an energy crisis, authorities have shied away from speaking publicly about the human cost of coal-power emissions and Eskom has rejected previous requests by the Mail & Guardian to see its research, saying these figures are of “limited use”.

Latest disclosures

The state-owned enterprise has never released information linking its coal stations to severe health problems. But the latest disclosures are contained in reports from 2006 that Eskom was forced to release after nongovernmental organisation Centre for Environmental Rights filed a Promotion of Access to Information Act application.

The reports were “prepared on behalf of Eskom Holdings”, which, it said, “wishes to understand the impact of currently operational power stations on the health of communities”, as well as the impact of future power stations.

Although the new-generation Medupi will be more efficient, a report estimates that the number of pollution-related deaths in the area will double. (Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

Medupi, which will be one of the world’s biggest coal-power stations with an output of 4 800 megawatts, will kill an average of 1.4 people a year, according to the reports.

Robyn Hugo, an attorney at the centre, said that it was the first time such a study had been made publicly available.

The reports were prepared for Eskom by the consultancy Airshed Planning Professionals.

No information

Communities previously had no information on which to base demands for improved air quality or healthcare, or to go to the courts for compensation. No research on this scale has been done subsequently.

The 276-page report on Mpumalanga found that air pollution in the province killed about 550 people a year and hospitalised about 117 200. Household fuel-burning was responsible for half of this, with Eskom responsible for 3% of deaths.

“Current Eskom power stations are cumulatively calculated to be responsible for 17 non-accidental mortalities per year and 661 respiratory hospital admissions,” the report stated. Four stations were responsible for 95% of the deaths: Kendal, Matla, Lethabo and Kriel.

In 2006, Eskom was running 10 coal-fired power stations, with three new ones to be built and three mothballed stations to be returned to operation.

This was before the 2008 power crisis, but the report looked at its future developments and projected that, with the new stations, 617 people will be killed each year and 24 842 will be hospitalised. It said these deaths will be caused mainly by sulphur dioxide emissions, which the World Health Organisation says causes chest problems and cancer.

Source of deaths

When its new fleet is completed, Eskom will overtake household fuel burning as the biggest source of deaths caused by air pollution, the report stated.

Three million people live in areas in which Eskom is expected to be responsible for at least one day a year of excess hourly sulphur dioxide emissions. Excess emissions from the Kendal power station alone had affected a possible 124 000 people by 2006, it said.

“Assessing source contributions to cumulative concentrations, it is evident that Eskom power station operations contribute very significantly to sulphur dioxide air quality limit exceedances [sic] within Mpumalanga and parts of the Vaal region,” according to the report.

By 2006, the Matimba plant was responsible for an average of 1.2 deaths a year. (Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

When the new and de-mothballed plants come into operation, the parastatal will raise sulphur levels as far away as Johannesburg and Tshwane, it predicted.

The Mpumalanga report also said that Eskom repeatedly exceeded air quality limits, which have since been greatly lowered by new air quality legislation.

“Sulphur dioxide concentrations have been measured to exceed short-term air quality limits at all of the Eskom monitoring stations,” it said.

The same applied to nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter.

Exceeding the limit

At Kendal, currently the largest station in the country, the hourly limit had been exceeded up to 200 times in the three years before the study. The advent of the new stations is bound to lead to “significant noncompliance” with the limits, it said. “The magnitude, frequency and spatial extent of such noncompliance are expected to increase significantly.”

The report for Limpopo said that when Medupi is operational, of those living within 25km of the power station, it will kill 1.4 people a year and put 144 in hospital. Its 200m-high stacks are expected to spread emissions over the area, including the town of Lephalale, which had a population of 22 000 when the research was done. It now has 60 000.

The report stated that people will die from the emission of sulphur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter, which cause chest problems and cancer.

The nearby Matimba plant already kills 1.2 people a year, it said.

It refers to Medupi as Project Alpha, which was still in the planning phase. “Project Alpha and [name redacted] would result in health risks being doubled from 1.5 to 3 premature deaths and from 144 to 300 respiratory hospital admissions per year,” it said.

The deaths could be decreased if flue gas desulphurisation technology is used, lowering sulphur dioxide emissions by 90%, it said.

World Bank requirement

This is one of the requirements of the World Bank loan given to Eskom for Medupi’s construction.

The report said the use of such technology would lead to “the avoidance” of about one mortality and 50 respiratory hospital admissions a year.

The technology is being built into Eskom’s other new power station at Kusile in Mpumalanga, but the utility has asked for its introduction at Medupi to be delayed until 2027.

Earlier this year, it told the M&G this was because of water constraints and that delaying Medupi would lead to prolonged periods “when Eskom is simply unable to meet the national electricity demand”.

Matimba was started in 1981 in Lephalale, near the Botswana border, with Eskom saying the location was chosen “due to concerns about the air pollution levels around Witbank [eMalahleni]”.

Impossible link

Previously, and again this week, Eskom said that it was impossible to link its operations to health problems. It said there were so many other sources of air pollution that blame was difficult to attribute.

When the M&G asked whether its stations were killing people, Eskom avoided giving a direct answer and said: “Studies have shown conclusively that the primary contributor to negative health impacts is domestic coal and wood burning.” Therefore, the best way to improve people’s health is to provide them with electricity, it said.

The 2006 Limpopo report states that Matimba, the coal mines that supply it, a brickworks and people burning fuel in their homes were the largest sources of emissions in Lephalale.

About 1.5 “premature mortalities” and 140 “respiratory hospital admissions”, for conditions such as asthma attacks, are caused as a result every year. But the report says Matimba is responsible for 80% of these mortalities (1.2 deaths) and half of the hospital admissions annually.

Emissions are supposed to be controlled by South Africa’s laws. In 2005, serious work began on creating new legislation and, in 2010, the National Environmental Management: Air Quality Act was passed. It puts significant limits on the emission of dangerous compounds such as sulphur dioxide and mercury, as well as carbon dioxide, which accelerates global warming.

Emissions caps

Eskom, as the largest air polluter, was integral to the discussions. The result was caps on its existing stations, to come into effect in 2015 and 2020. Construction on Medupi and Kusile began at that time, with Eskom saying their emissions will be lower than those of the older plants.

But the utility has already applied for postponements for its whole fleet, which will see them not having to lower their emissions until the next decade.

This week, in response to questions, Eskom said “the issue of assigning a cost to a health effect or a human life” is “always contentious” and Eskom “just uses values derived by international or local independent experts”. Quantifying its own impact on human health is extremely difficult because of the “enormous number of factors” that impact on human health in general, the utility said.

The brunt of air pollution that people face is because they burn wood and coal in their homes, it said, so the best way of improving air quality is to electrify more homes.

To ensure its impact is lowered, Eskom said it is embarking on an “extensive emission reduction programme” over the next two decades.

Emissions are like inhaling ‘burning coals’

Eskom’s most problematic station is outside the tiny Mpumalanga dorp of Kriel. A hundred kilometres east of Johannesburg, it is at the centre of South Africa’s power generation hub. Eight power stations are within 100km.

The Mpumalanga coal seam runs through the region, which is why Eskom jockeys with green fields for water and space.

To the north is eMalahleni, meaning “place of coal”, and to the south is Secunda, with the world’s worst emissions from a single point. This is one of the most polluted places on Earth.

The Kriel power station is indicative of Eskom’s wider problem. It is running a fleet of decades-old power stations with demand often exceeding supply, forcing it to push back maintenance. Power utilities aim for at least a 15% reserve, but Eskom has maybe a third of this on a good day.

Medupi and Kusile were supposed to solve this but the 4 800MW Medupi plant in Lephalale has been delayed for several years and its first unit will only come online early next year. The result has been blackouts. Eskom would begin to retire the old stations from 2024.

When the Mail & Guardian visited Kriel recently, residents said the local power station and the Matla station across the valley from it were affecting their health.

Living just 300m from the power station, Robert Woods said, when the emissions blow in his direction, the air he inhales is “like burning coals”. Like many others, he has a constant cough but says he has not been to a doctor because health problems lead to people having their contracts terminated by employers.

The town itself, neatly ordered and well kept, relies on Eskom and coal mines for survival. This made people cautious when they spoke about their health.

But Thubane Timunye bluntly said: “These stations are killing me.” He said sleeping was a problem because of incessant coughing.

“How can we ever get justice if we cannot afford lawyers?” another resident asked.

A question of energy versus health

The National Environmental Management: Air Quality Act allows emitters to delay compliance with the Act by submitting their reasons to the department of environmental affairs.

Eskom has asked for “rolling” postponements for all its coal power stations, mainly because it would cost R200-billion to ensure compliance and the power grid is too constrained.

In its preliminary response, the department found fault with every submission, citing a lack of information on actual emissions, and that the requests did not include air pollution dispersion models based on observations. The models submitted were based on estimates.

In the case of Matimba, the department said: “There is no indication of planned compliance into the future.”

Eskom’s application to triple the particulate emissions at Kriel in Mpumalanga was rejected by the local Nkangala district municipality. It told Eskom that the information the utility had submitted was not truthful. In its request, Eskom cited the poor quality of coal going into the plant, its age and the power crisis as imperatives to lower air quality requirements. It said emissions were “highly erratic” because of the “unreliability of many of the plant’s components”.

In its application to postpone compliance at Medupi, and to bring flue gas desulphurisation (technology to cut out 90% of sulphur emissions) on line only in 2027, the parastatal said there was not enough water available to introduce the technology. “It is not practically feasible or beneficial to South Africa to fully comply with the minimal emissions standards.”

Eskom now has to resubmit the information and wait for the department to balance the need for power with the continuing health impacts of Eskom’s fleet.

The Act allows for R10-million in fines and/or 10 years in jail for contraventions. — Sipho Kings