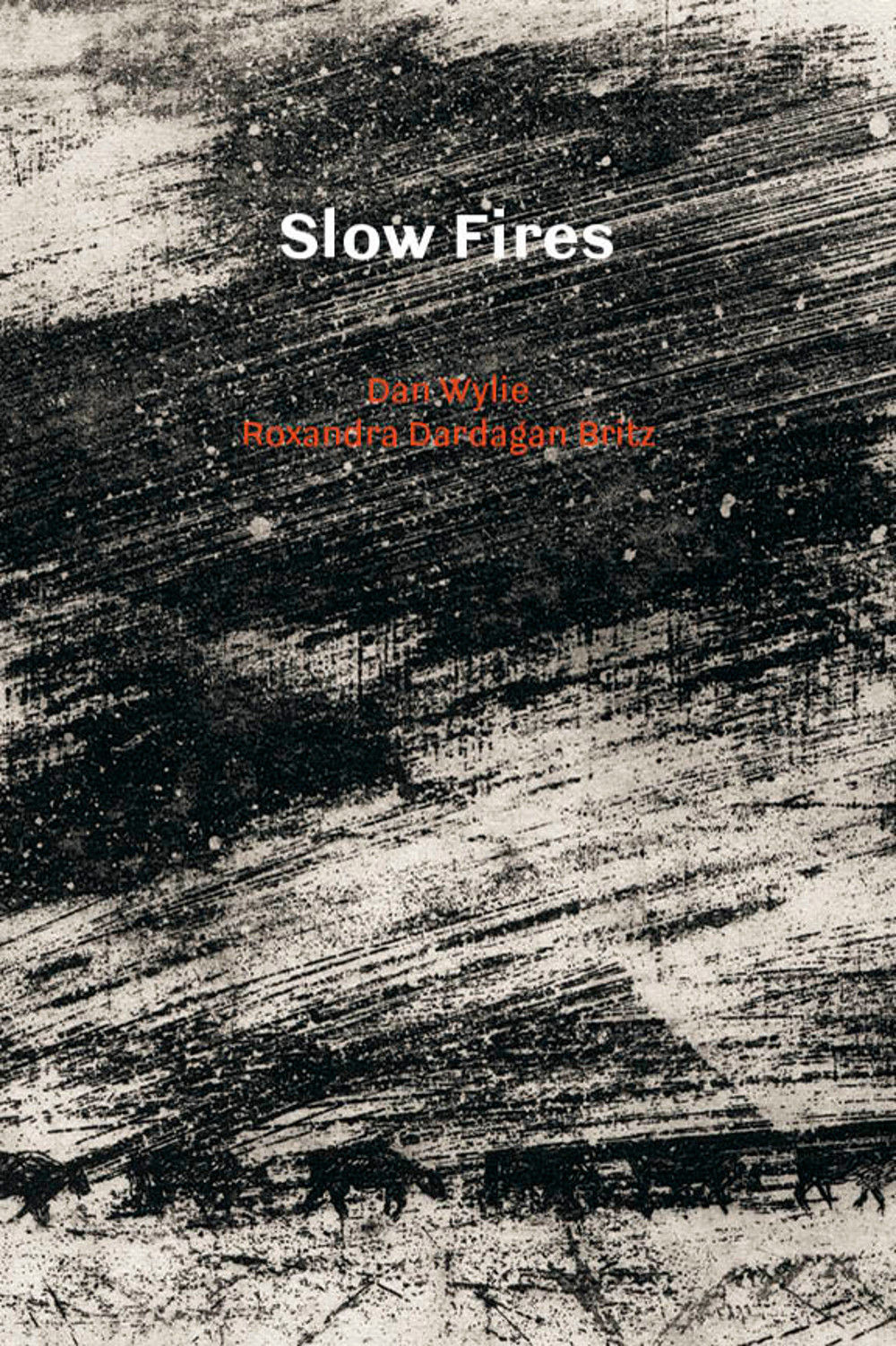

Prints by Roxandra Dardagan Britz accompany words by Dan Wylie in 'Slow Fires'

SLOW FIRES with etchings by Roxandra Dardagan Britz and poems by Dan Wylie (Fourthwall Books)

Frogs and wild dogs and elephants, an ostrich with its head in the sand, a secretary bird with diverse opinions, a hornless rhino and herds and herds of cattle bound in one direction amid torrents of texture.

These are just some of the main characters in Slow Fires, a deliciously unfashionable offering of poetry and printmaking.

Is it fair to force animals into synthetic personae and political rubrics? Can human-made associations obnoxiously bruise their authenticity? Or whittle their realities down into mere ciphers of the rumbling beast that is our society?

Artist Roxandra Dardagan Britz and poet Dan Wylie engage with this question in their wise, sophisticated, witty and beautiful collaboration, yielding 24 distinct pieces.

No questions are addressed directly, as no animals are named throughout this jewel of a book. Rather, from the shambling shadows of a hyena to the cattle that perish like humans, or the elephant that gloriously watches us over aeons, not to forget the dung beetle that speaks of an inordinate fondness of others of its ken, this publication reeks of succinct and thoughtful description, whether it be in intaglio or with words. And it is so beautifully crafted it will make you ache.

The book is one that you can read relatively quickly or dip into on the spur of the moment, but ultimately, it’s eminently haveable.

It’s created in a style evocative of old traditions that heralded the gem-like status of the indefatigable craft of poetry and etchings.

On a level, Slow Fires, a book of poems and pictures about animals, embraces a sense of simplicity that almost reaches a childlike sensibility, but this is no child’s book.

A fine fabric of association stretching from Zimbabwe to Grahamstown binds the content of the book into a satisfying, if disparate, whole.

Wylie and Britz come from Zimbabwe. They live in Grahamstown. Their collaboration holds the foibles of contemporary society with all its sham, drudgery and broken dreams and its ugly war-related histories under the loupe, and it is here that we are shown the horror of rhino massacre, a dog crushed in traffic and the displaced and dispossessed of society in the face of xenophobia.

Each animal is lovingly described with carefully woven threads of association to a political context, and the titles of the poems are accredited in a section at the back of the book, reaching from the Bible and Tao Te Ching to the memoirs of Ian Smith and the ideas expounded by Zimbabwean social commentator Martin Meredith. Thus each word or phrase is given new life and a fresh context.

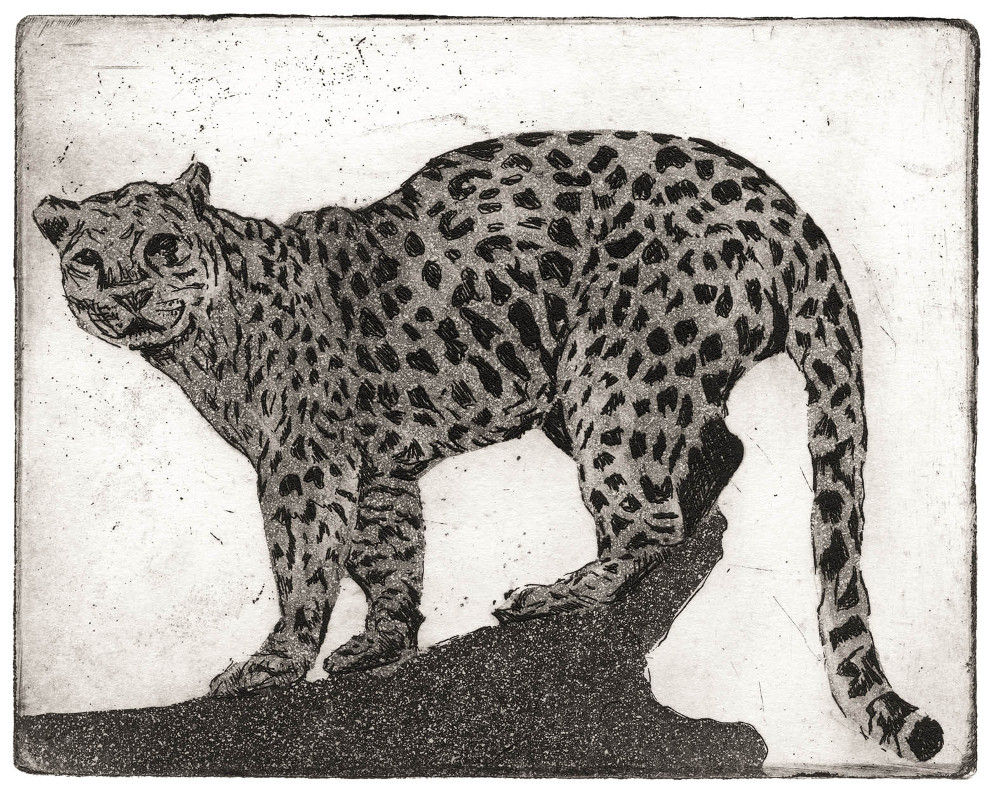

Working with a diversity of traditional etching resists, from hard ground to spit biting, the latter allowing an errant uncontrollability in the conversation between black ink and white paper in her work, Britz yields a series of works that is compelling without becoming too literal.

The astonishing dust cover of this publication, titled Exodus, reflects a queue of cattle, their heads down, walking in the path of dramatic tone and, by implication, weather. The texture is harsh, the sentiment abrasive yet deep.

And, throughout the book, facing each poem is an etching bearing Britz’s distinctive approach. Balancing line work with tone, working with the challenges and visual shock of extreme density or its lack, the works are self-standing and dignified. She proves herself a master of aquatint etching: the application of tone to an etched image, achieved with the sprinkling of resin; the levels of subtlety she attains are satisfying and beautiful.

But more than this, Britz reaches a level of characterisation with these animals that never slips into caricature or cartoon; they also don’t lose their sense of levity. The pig is iconic, almost like a plastic farm animal, the leopard majestic in its sense of self. There is an elephant that leans out of the confines of Britz’s etching plate and a warthog you might want to hug in its embrace of the “blunt, squealing conscience of the world”, in Wylie’s terms.

Immense endearment, empathy and fascination with each animal’s physical and metaphorical idiosyncrasies are embraced in the astonishingly close intertwining of word with image, making this a timeless book, a paean to Zimbabwean history and a keepsake.

The give-and-take between poet and artist is never forced or literal, making the dovetailing of the words with the image particularly pleasurable and unpredictable.

Ten, 20 years ago, a generation back, this book would have been leatherbound, its images celebrated behind spidery-thin paper and printed on special bond. But today, with solid, satisfying design and, albeit between paper covers, this book is no less exciting and precious.