Samuel Masetlha's life has been transformed after being fitted with an artificial limb.

Samuel Masetlha stands up tentatively. His legs are shaking as he leans on his crutches for support with every cautious step.

Like a child taking his first steps, Masetlha stops often to regain his balance. He smiles, revealing toothless gums as he stares incredulously at the brand-new takkie on the foot of his new prosthetic leg.

For the first time in two years, Masetlha can stand on his own two feet – without any help.

But the memories of the car accident that claimed his leg remain vivid.

On a cold May evening in 2012 Masetlha and a friend were walking home from work along the busy Simon Vermooten Road in the east of Pretoria, when a driver in a white Citi Golf sped past the two men – hitting Masetlha.

“By the time the driver looked in his rear-view mirror I had already fallen. But he just raced off. He never even stopped to see if I was dead or alive.” Masetlha keeps his head down as he talks about the incident.

“That guy was in a hurry to get to wherever he was rushing to. He couldn’t overtake the cars in front of him from the right side, so he decided to overtake from the left. We were oblivious of any danger because we were sure that we were safe walking on the left-hand side of the yellow line,” he says, trying to shrug off the memories.

Damaged beyond repair

Although he spent almost four months at the Steve Biko Academic Hospital, Masetlha’s leg was damaged beyond repair.

“The doctors told me that my leg would never heal. They told me that the leg is dead, it will never walk again and that it was best to just cut it off.”

Masetlha shakes his head as he rubs his right knee, just above the spot where his leg was amputated.

“I couldn’t understand how that was possible. But the bottom part of my leg was dead, so I had no choice but to give in and let them take it.”

Pretoria resident Samuel Masetlha lost a leg when a car hit him, rendering him largely immobile. (Photos: Madelene Cronjé)

The sudden disability changed Masetlha’s life for the worse. Spending almost four months in hospital meant that Masetlha couldn’t work and therefore fell behind on his rent.

Without a leg, he couldn’t go back to his construction job and could not guarantee that he would be able to make enough money to pay the R450 monthly rent for the room he was leasing in Mamelodi.

“I remember thinking that it would be better if God just took me,” he recalls. “I didn’t have a place to stay. I couldn’t work, so I couldn’t go back home to my family in Steelpoort near Burgersfort in Limpopo.”

Makeshift camp

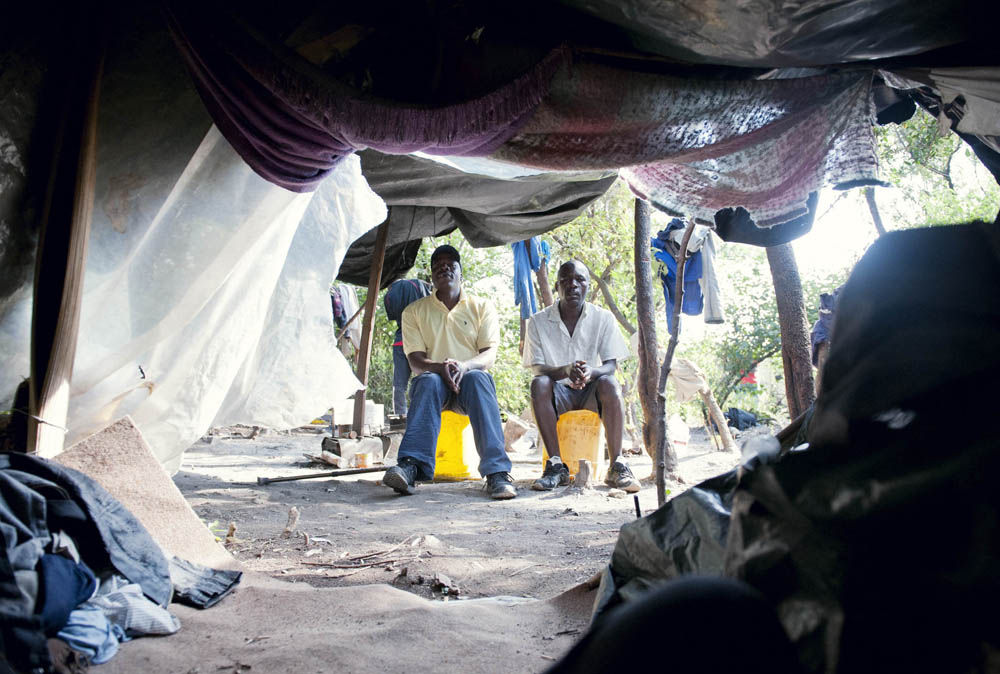

Some of the people Masetlha knew before the accident invited him to live with them in the makeshift camp they had set up in open veld across the road from the affluent residential estate of Silver Lakes, east of Pretoria.

Here, Masetlha and his small group of friends sleep in tents made of discarded fabric and branches broken off from the surrounding trees. They have no electricity and their only source of water is a nearby dam.

A recent study by the University of Johannesburg-affiliated Centre for Social Development in Africa exploring the link between poverty and disability found that, like Masetlha, people with disabilities are “less likely to be able to earn an income” and therefore “disability may increase the risk of poverty”.

One of the report’s recommendations concerns the provision of “complementary services like access to assistive devices …

“Such interventions could promote the economic participation of those who are able to do so.”

Though the study found that just over half (56%) of people with disabilities live in urban areas, those in poorer and rural communities have a lower quality of life than their urban counterparts because of a general lack of resources such as access to healthcare, quality education and infrastructure.

Artificial limbs

Fortunately, Masetlha is one of the beneficiaries of Mobility 4 Life, a nongovernmental organisation that provides artificial limbs to amputees from rural and poor communities.

The organisation estimates that there are 25 000 amputees like him who cannot access prostheses because of issues such as long waiting lists at private or public hospitals where the services are usually provided.

Although it was awkward for him in the beginning, Masetlha can now walk comfortably. He has started working, something he could not do for the past two years.

With money collected from corporate social investment initiatives, the organisation hopes to assist more people who do not have the means to access even the most basic of primary healthcare.

The key focus of Mobile 4 Life is to bring prosthetic services to remote communities by making use of the modular socket prosthesis system. This allows for the socket to which the prosthesis is attached to be made directly on the patient’s stump –instead of the conventional prosthesis where the socket is manufactured in a factory.

The new technology allows for artificial limbs to be fitted in less than an hour in any environment.

Ongoing intervention

Along with a new limb, amputees like Masetlha will receive ongoing intervention that includes quarterly check-ups with prosthetic specialists and physiotherapists to ensure that the prosthesis still fits, and rehabilitation to help them adjust to the limb for the first 12 months after the prosthesis is fitted. After 12 months they will get a new leg.

Now, a week after Masetlha was fitted with his new leg, he is still getting used to his new-found freedom. He is walking with the aid of one crutch instead of two. Despite his slow stride, he has already landed work for a day this week. Masetlha and some of the men he lives with in Silver Lakes were hired to paint a room at a crèche.

“I still use the crutch to help me balance because it is very rocky there where I stay. If the surface was even I would lose the crutch sooner,” Masetlha smiles, revealing the dimple in his right cheek. “It doesn’t hurt; it is just a little bit uncomfortable when I step on the leg.”

The 40-year-old father of two says he has lived off the goodwill of others for two years and is very excited to get his life back together again.

“I didn’t feel good about myself, especially when I saw other people walking normally. But the men I live with always encouraged me not to give up,” Masetlha says, barely containing his excitement.

“Now that I’ve got a new leg and I am comfortable with it, I will be able to work and take care of myself and do anything for myself. If I can find work, I will be able to save money and make plans like starting a business. But what’s most important is to get a job, and then I’ll be all right.”

Heavy price of road accidents

The Automobile Association (AA) has found that, every day, 22 South Africans sustain serious injuries in a road accident that leave them permanently disabled.

- The direct hospitalisation and rehabilitation costs in a road accident where someone becomes either a quadriplegic or paraplegic can exceed R1?million a person; a further R500 000 would be required to “maintain a semblance of quality of life”, according to the AA.

- The Road Traffic Management Corporation estimates that pedestrians account for just under 40% of road accident fatalities.

- A fatal crash happens every 48 minutes in South Africa, according to the AA.

- The South African Journal of Surgery estimates that there were 13 802 deaths from road accidents in South Africa during 2011. According to the 2011 South African Census, 2.3% of the country’s population use wheelchairs; 3.2% use walking sticks or frames.