The rubble in Tacloban.

As sounds of traffic float into Ian Grose’s studio above Longmarket Street in Cape Town, the soft-spoken artist is telling me about the paintings that form Some Assumptions, his new solo show at contemporary art gallery Stevenson.

He says they’re a way of asking how “these funny, anachronous objects have any function” when “everyone has a camera in their phone and you can enact the miracle of representation in a second”, resulting in a world “awash with images”.

The 2011 Absa L’Atelier winner believes he’s at the beginning stages of two paths: one is “figuring out paintings for myself”; the other is “figuring out how to make paintings for myself and for others”.

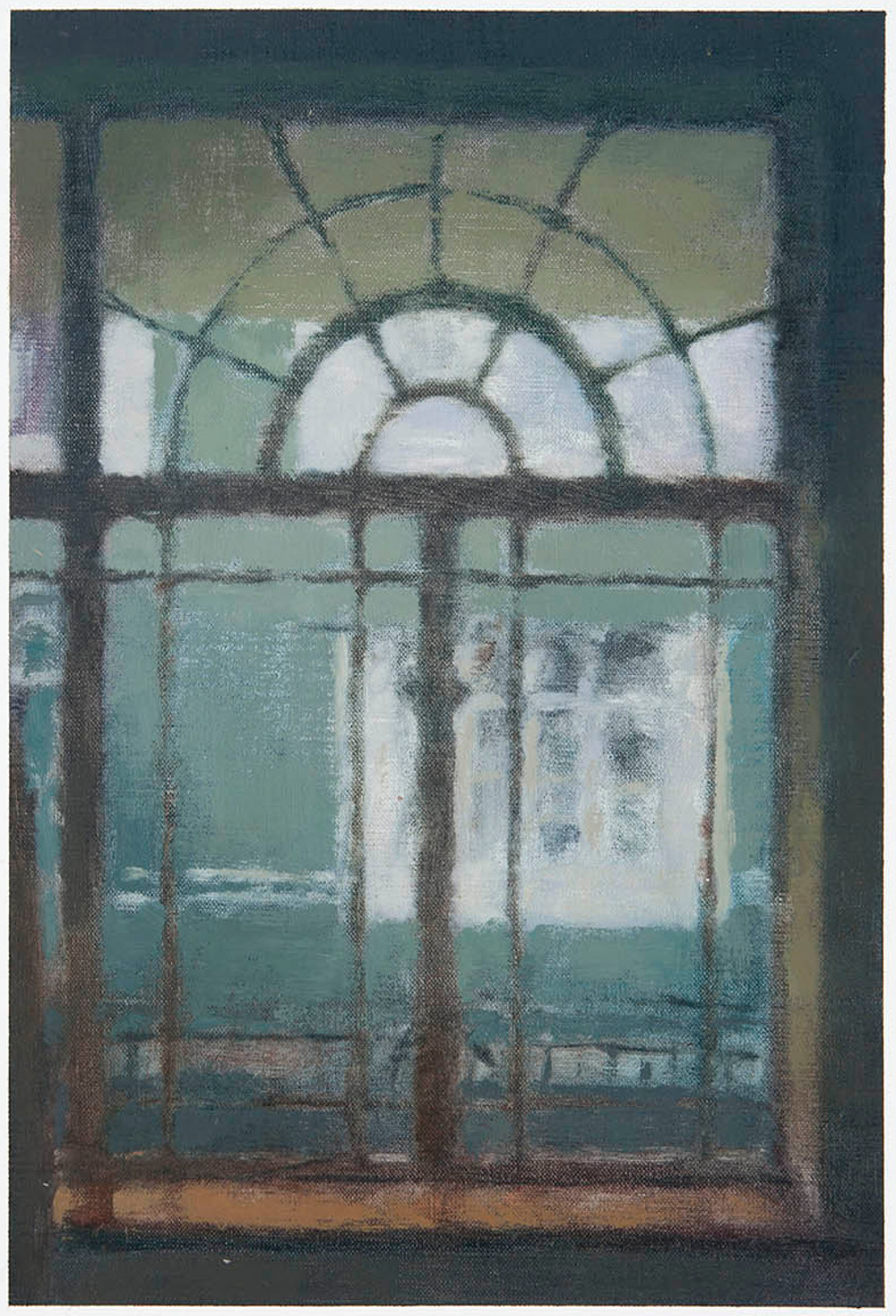

‘Studio Window (Winter)’ by Ian Grose.

Grose wants to make paintings “that work”: an image that “pulls your eye and your mind back to it and you can dwell in the painting for a long time, visually, and also … you can constantly work out different meanings – or it just seems there’s a kind of inner mystery to it that you can’t quite get to the bottom of.”

When he produces paintings that he feels “work”, he keeps them on the wall of the studio and looks at them every day. “After two weeks, if [it’s] still doing something, then I feel there’s an inner engine to it and it’s just going to keep running.”

Physical effect

Grose finds painting a mysterious challenge that has real rewards. “I’m very sure about my responses to other people’s paintings,” he says: the ones he loves have a physical effect on him – his breathing slows. But increasingly he is also confident about his responses to his own paintings too.

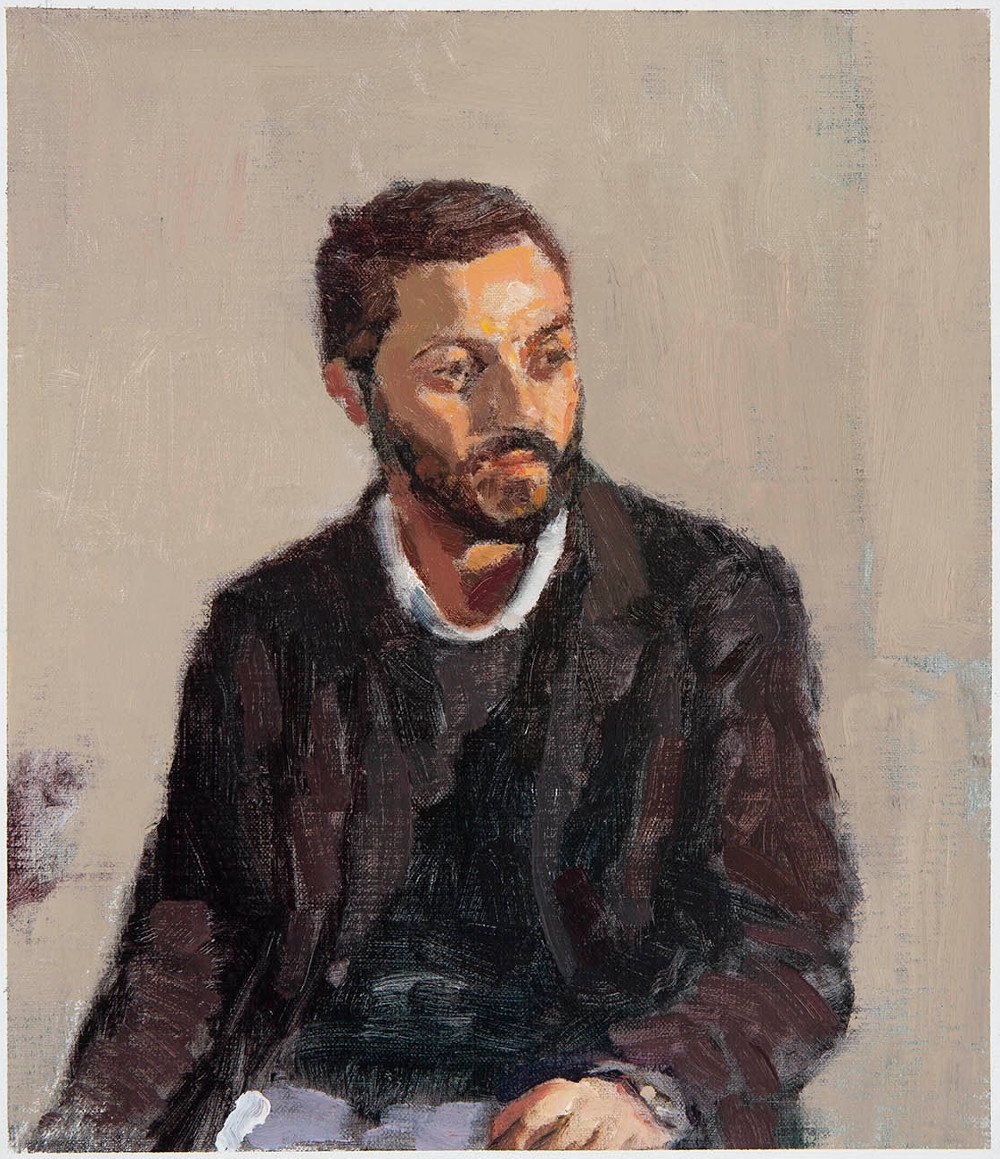

‘Refrain 2’ by Ian Grose.

Offering more questions than answers, he invites the viewer to engage with the ideas that intrigue him. “I don’t feel like I want to be explicit about anything.” Rather, he wants to animate “knots of ideas”, bringing “them together in a certain way that’s reflecting literally my assumptions – what I take to be important”.

So what’s important? Well, firstly, according to Grose, a painting’s “tension between being an image that lets you through as a window and that asserts itself as a surface”.

‘Still Life’ by Ian Grose.

This tension is most forcefully explored in the Assumption series (one of the four sets of paintings that form Some Assumptions), in which Renaissance-inspired scenes of the Virgin Mary ascending heavenwards have been almost obliterated by brushstrokes using paint from the same palette as the image underneath. It is also apparent in the Dissimulation paintings, where floral fabrics have been rendered with folds and undulations.

Grose’s preoccupation with light and colour is manifest in a series featuring his studio window at different times of the year – the same scene, but each wondrously different.

Portraits

The exhibition’s final series consists of portraits of friends he has painted in his studio. He says painting from life has resulted in surprisingly lively mark-making that is a lot more honest than the steady coldness that comes from making work from photographs … because there’s really no time to second-guess.

Mark-making has the power both to communicate and to obfuscate, yielding layers of meaning that are sometimes conflicting. “You can have a set of marks that’s descriptive and concealing at the same time,” he says.

A blob of paint could be a shadow of a nose – or just a blob. “You can look at it and oscillate between seeing it in one way and seeing it in a different way.”

‘Alexis Karamazov (Thursday Evening)’ by Ian Grose.

Much of Grose’s work reveals his “focus on the plainest stuff around”. Something as ordinary as a friend sitting in a studio has a relationship to a plain fabric pattern: “in direct confrontation with them [both], they seem completely unremarkable” but they form the raw material from which he tries “to make a compelling image”.

“There is that base assumption of mine that you can make something out of anything,” he says. “I’m very aware of the absurdity of the whole exercise” of painting. I clearly have lines of thought to dispel that sense of ‘what I’m doing – this is crazy’ … A lot of the time I just go home exasperated because it seems like everything is lifeless. It’s trying to go after that weird, strange effect it can have on me – that’s the goal, I suppose.”

How does that relate to the world outside? “Ideally I would like to figure out the mechanics of meaning of painting in which it would be possible in some way to respond to the world, but that maybe is in the future,” Grose muses. “At the moment painting is complex enough. And I’m responding to it.”

Some Assumptions is on at Stevenson Cape Town, Buchanan Building, 160 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock until August 23. Visit stevenson.info for more information.