The favelas are served by teams of community workers

Graziela dos Santos (25) is walking down a street in one of Brazil’s favelas, Coahab Raposo Tavares, in São Paulo. Fast. As she travels down a hill, body lurching forward, Dos Santos’s arms swing.

Favelas are Brazil’s equivalent of South African townships. This one is in a part of São Paulo called Boa Vista and about 20 000 people live here. To be more precise, 19 903 people.

Dos Santos knows, because she helped to count them herself.

Raposo Tavares is home to all kinds of accommodation: government-subsidised townhouses and flats, self-built houses that are stacked on top of one another in a way that would leave even Londoners cringing with discomfort, and the shacklike homes that millions of South Africans would know well.

Dos Santos approaches one of the squatter homes. She knows everyone in this street. She also knows their business. In fact, she gets paid to know it; officially, she is required to visit each family in the area at least once a month. Dos Santos arrives at a dilapidated wooden structure surrounded by a steel fence, pencil and notebook in hand, and shouts: “Boa tarde! Como está? [Good afternoon! How are you?]”

A dishevelled woman in her late 20s, a string of toddlers at her chapped heels, appears at the gate. “You’re back so soon, Graziela?” she asks. “That’s good. I’ve got a question for you.”

Dos Santos wears a light-blue waistcoat, with “SUS” printed on the back. The letters are an acronym for Sistema Unico de Saúde, Portuguese for Unified Health System, Brazil’s public healthcare system, which was created in 1988.

Multidisciplinary team

She works for a nearby state clinic in Boa Vista, Unidade Básica de Saúde, where she is part of a multidisciplinary team comprising a doctor, a professional nurse, two nursing assistants and six community health workers like herself. There are six such teams at the clinic; each serves 3 500 of Boa Vista’s 19 903 people.

Community health workers are recruited from the communities where they are eventually deployed. As Dos Santos explains: “This is because we understand our own people the best.”

Just last week, the Mail & Guardian reported how several patients in the Free State had defaulted on their tuberculosis treatment because community healthcare workers were no longer available, after 2 200 of them were dismissed in April.

Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi wants to replicate the Brazilian community health worker model, and started with this when he announced the creation of specialised ward-based primary healthcare teams in 2011 as part of his plans for South Africa’s National Health Insurance scheme.

According to Mark Heywood of the social justice group Section27, the training of community health workers, however, lags far behind schedule and so does the policy-making process; no policy has yet been formalised.

Meanwhile, Dos Santos is responsible for about 150 families. She is able to rattle off the names of each family, how old they are, their medical histories, their clinic visits. She knows whether or not they’re receiving welfare grants. She knows whether they smoke and drink. She knows how much they smoke and drink, as well as their favourite brands of sin.

The wooden structure she is about to enter consists of about five makeshift rooms covered with rough, rusted corrugated iron. Alongside is a room made of brick. This area contains a toilet, a basin and a shower. The backyard consists of rubble, and that’s all.

The woman who opens the gate explains: “This used to be a rubbish dump until about two months ago, when we moved in.” She’s almost four months pregnant and is wearing a tight mini dress. Her name is Jacqueline Tais. “At first it was only about six of us, but within two weeks we were 34 – 28 women and six men. None of us has formal jobs and we’re all waiting for government housing, so we put up our own structures.”

Five women are home this afternoon; two of them are pregnant. Among them, they have eight kids. They are all single mothers.

Dos Santos opens her notebook. “Your next antenatal visit at the clinic is in two weeks,” she tells Tais. “They’re going to do a scan then and you’ll be able to see whether the baby is a boy or a girl.” Dos Santos also checks Tais’s four-year-old daughter’s immunisation card to see if it is up to date.

Same doctor every time

When Tais visits the clinic she sees the same nurse or doctor each time. Boa Vista has been divided into colour-coded areas; the same team works with the people in a particular area throughout.

Dos Santos, who underwent about a week of training before starting her job, earns 1 000 Brazilian real (about R5 000) a month and, like the doctors and nurses, is paid by the government. Each day she has an hourlong meeting with the rest of her team members to update them on what she has found in the community.

Dos Santos is literally the doctors’ and nurses’ “eyes and ears”, according to the doctor in her team, Rodrigo D’Aurea. “We can’t relate to patients in the same way that community health workers do. The health workers bring ‘the reality’ to doctors and nurses because patients have a social, and not just a medical, link with them. They relate to them on the same level.”

When the family health strategy component of Brazil’s public healthcare system was implemented in 1994, it leaned heavily on community health workers because Brazil, like South Africa, had a serious shortage of doctors and nurses. According to a 2013 study in the journal Globalization and Health, Brazil’s 257 265 community health workers now cover just over half of the country’s population.

They make sure pregnant women get the care they need, help young mothers with breast-feeding problems, check whether children receive their vaccinations and ensure that people take their chronic medication correctly.

For those patients who are not physically able to visit a nearby clinic, such as the elderly or women who have just given birth, community health workers book home-visit appointments.

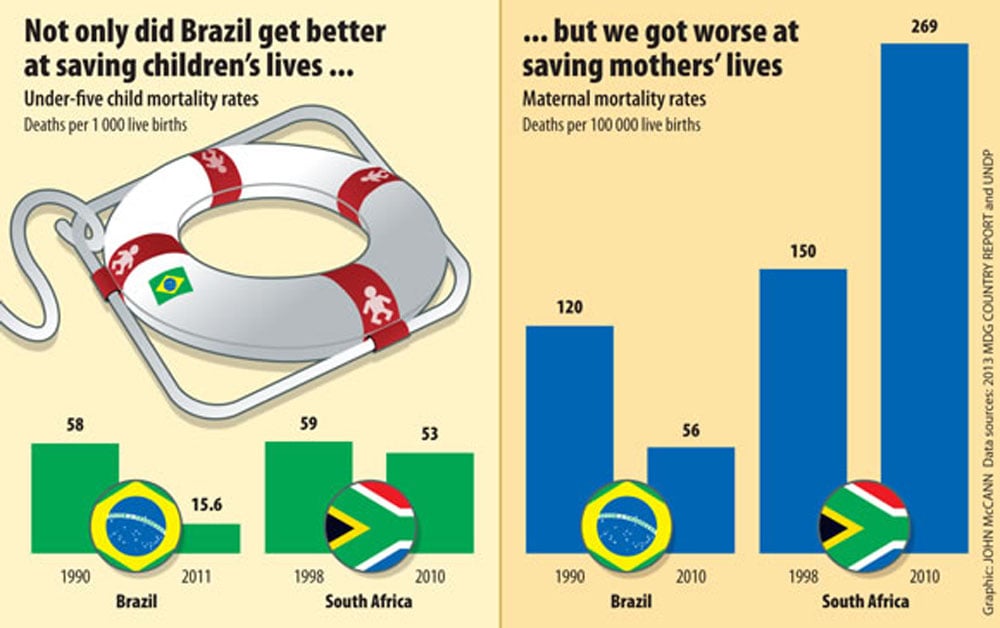

Numerous studies have shown that Brazil’s community health workers have been largely responsible for a two-thirds drop in mortality rates of children under five, from 58 per 1 000 live births in 1990 to 15.6 in 2011, according to United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) figures.

Brazilian studies have confirmed that community health workers in the rural north-east of Brazil have, for instance, significantly helped to increase the uptake of vaccines (resulting in fewer children developing preventable diseases) and breastfeeding (which is closely associated with lower infant mortality rates).

Preventing disease spread

A Stanford University study in 2008 highlights how a community health worker reported a child with meningitis symptoms straight away and thereby prevented the spread of the disease. The study also points to the case of a doctor who reported that half of the mothers he saw did not understand how to read their children’s vaccination cards without help from community health workers.

In sharp contrast, South Africa’s under-five mortality rates, according to the 2013 Millennium Development Goals Country Report, are more than triple that of Brazil’s, at 53 per 1 000 live births.

UNDP figures show that Brazil’s maternal deaths have also more than halved from 120 per 100 000 live births in 1990 to 56 in 2010, and women are now having an average of 1.9 children compared with 5.8 in 1970. According to research studies, community health workers have played an important role in helping to increase the number of women receiving contraceptive advice from a doctor.

South Africa’s maternal mortality rate, according to the 2013 Millennium Development Goals country report, is almost five times that of Brazil’s, at 269 per 100 000 births.

Jeanette Hunter, the South African health department’s deputy director general for primary healthcare, says provincial health departments have started to train ward-based community workers. But Heywood points out that this process is being implemented too slowly and that the health worker-to-patient ratio will be far lower than that of Brazil.

Back in Boa Vista, Tais tells Dos Santos about a pain in her stomach, near her cervix. “I’m going to talk to the doctor about this and ask him if it’s necessary to book you for a Pap smear when you come to the clinic for your pregnancy visit, because we need to find out if your cervix is okay,” Dos Santos says. “The sooner we find out what the problem is, the better.”

In Brazil, the bridge between patients and doctors is in the form of community health workers like Dos Santos. In South Africa, that bridge has yet to be constructed.

Mia Malan visited Brazil in April as a fellow of the International Reporting Project. This is the second in a series on community healthcare workers. Next week, we’ll focus on community health worker training and policy in South Africa.