The word asbestos can clear a room, but in the case of Bulembu – a small town in northern Swaziland – it was the end of its production that cleared an entire town. Once used in thousands of products, from brake pads to putty and cement, the fibrous mineral has been outlawed in more than 50 countries in the two decades since it was linked to a range of deadly lung diseases, including asbestosis and cancer.

Bulembu is positioned among stark, grey 150m-high asbestos dumps that experts say could poison the lungs of residents, and kill them slowly and painfully over decades. Today the town is home to about 350 Aids orphans and, according to its website, there could be 1 000 by 2020.

Between 1939 and 2001, Bulembu operated as a chrysotile, or white asbestos, mine. In the 1960s Havelock Mine, as it was then known, was one the biggest producers of asbestos in the world, churning out 42 000 tonnes a year at its peak in 1976.

By 1991, Turner & Newall, the United Kingdom-based conglomerate that operated the mine, was facing massive compensation claims from lawyers in South Africa and Britain as evidence of the danger of working in its mines and factories became undeniable. Payouts of these claims, combined with plummeting demand for asbestos, eventually saw the company fold.

HVL Asbestos Swaziland then took over the operations, but went insolvent in 2001 after 10 years of operation. All but about 50 of the 10 000 residents left the town in a matter of days, according to several people who lived there, and it became a ghost town. Over the following years, schools, hundreds of houses, a members’ club and a movie theatre stood empty and slowly decayed.

But all that changed five years later in 2006 when the town, with all its infrastructure and 1 700ha of surrounding land, was taken over by Bulembu Ministries Swaziland, a nonprofit Christian organisation.

The price? A bargain basement $1-million – at an exchange rate of R6 to $1 – according to Neal Rijkenberg, one of the directors of the Bulembu Ministries, who donated his 50% of the property to the ministry. (See correction below)

Legal wrangles

Andrew le Roux, a former executive of Bulembu Ministries Swaziland, said the low price was owed, among other things, to protracted legal wrangles with the former owners and the need to restore the town’s infrastructure.

Despite the dumps that line one side of the town, the ministry deemed it safe to establish an orphanage there. Asked why he had chosen to use Bulembu, Rijkenberg said: “I am a Christian. I felt that God had brought me here.”

Aids orphans walk to a school in Bulembu, past a potentially deadly mound containing asbestos, a leftover from the days when the substance was widely mined and used. (Photos: Delwyn Verasamy, M&G)

Rijkenberg and Le Roux said much of the funding for the town came from international philanthropists. Asked whether any of the donors were aware of the potential danger of asbestos to the children, Le Roux said: “Of course; a lot of them sit on the board.” But Rijkenberg and Le Roux refused to provide names or contact details of any of the philanthropic individuals, saying such queries could cause funding to dry up.

Rijkenberg and the other members of the ministry believe the town is safe. He said air tests had convinced them there was no danger from asbestos in the environment. “Show me one child who’s contracted an asbestos-related disease,” he said.

According to Rijkenberg and Le Roux, the dumps are covered with a hard crust, so no dust blows into the town during windy weather.

Mining-related illnesses

During just such a dry and windy time of year Jock McCulloch came to Bulembu. A professor at Australia’s RMIT University who specialises in occupational health and politics, McCulloch has written extensively about mining-related illnesses in Southern Africa.

In the opening paragraphs of an academic paper published in the Journal of Southern African Studies on the history of the Havelock/Bulembu mine, McCulloch writes: “The day I visited … in July 2002 … it was windy, and fibre was being blown over the entire settlement, including the primary school.”

The Mail & Guardian visited Bulembu recently; there were hundreds of square metres of loose, friable grey soil at the bases of the dumps.

The Aids orphans live with their caretakers in the neatly painted houses in the Swaziland town, which was all but empty until recently.

McCulloch last week gave a rough estimate that the dumps were made up of between 3% and 5% asbestos, saying: “The mining process was crude and not all the fibre was mined out.”

He said fibres are visible to the naked eye in the dust of the dumps. “I wouldn’t have taken my child [on to the dump] because of the latency period [for diseases such as mesothelioma to set in].”

Rijkenberg said there is no evidence that any of the nonmining residents of Havelock/Bulembu have ever contracted an asbestos-related disease.

‘Charging elephant’

But Tia Litshka (45), whose father worked on the mine, said he and three of his colleagues had died of lung complications. “I wouldn’t go back there,” she told the M&G in August. “It’s like standing in front of a charging elephant. It’s completely irresponsible what [the ministry] is doing [by bringing the orphans there].”

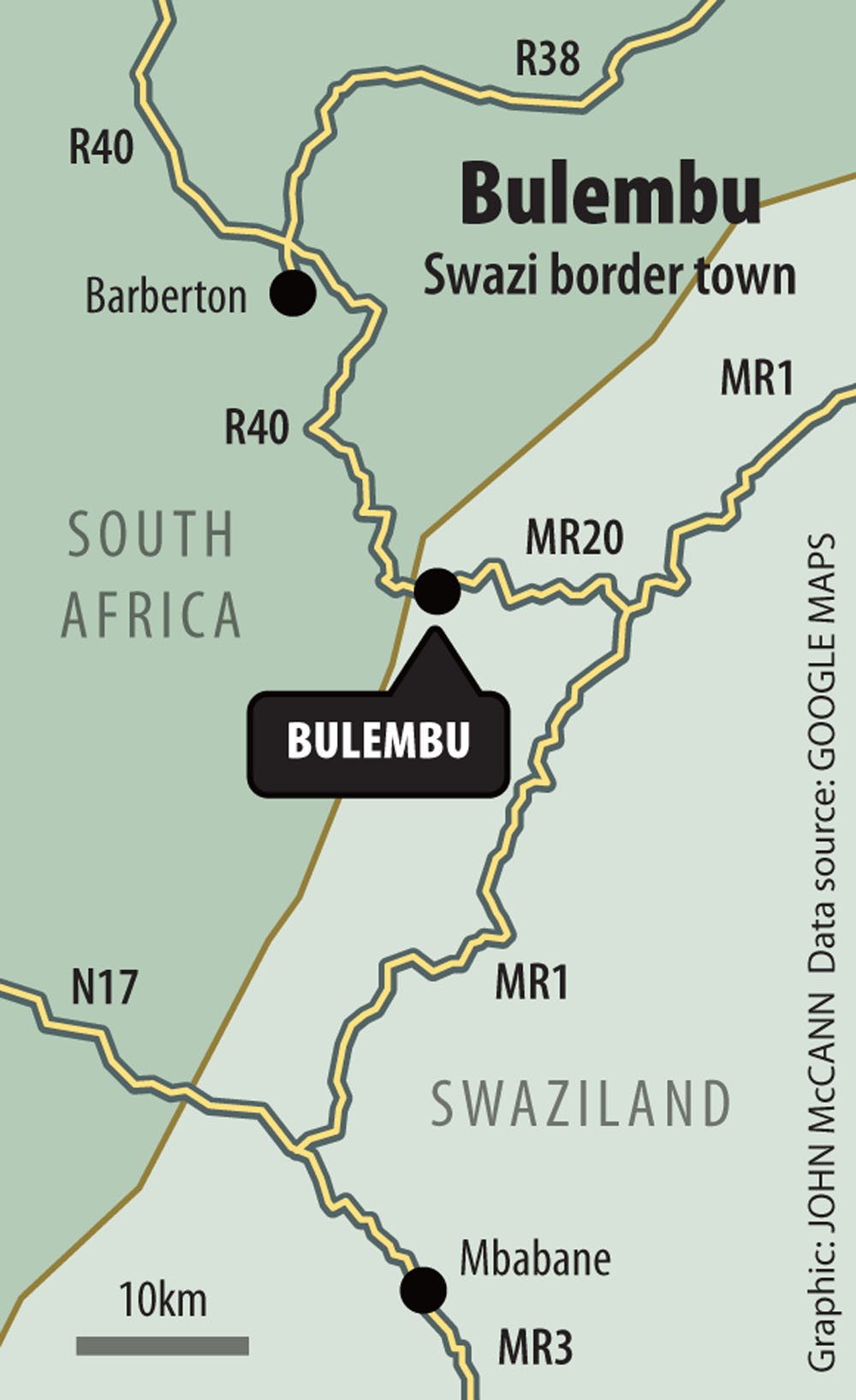

Set in the mineral-rich Makhonjwa mountain range that runs from Barberton into Swaziland, the area around Bulembu is visually spectacular. Entering from Piggs Peak to the east, you pass through a boom gate at the town entrance. A sawmill appears on the right and then an idyllic scene of dairy cows grazing in green fields unfolds on the left. A multicoloured grid of square houses covers a slope down a valley facing directly on to the bare asbestos dumps.

Opinion is divided as to what constitutes a ‘safe’ level for asbestos, but many believe a zero level is the only safe one.

The town is spotless, with pristine, whitewashed buildings up and down the hills on both sides of the road. Several are adorned with religious slogans. The town is eerily empty, apart from a few adults walking along the roads.

The original lodge has been renovated and offers plush rooms at the modest price of R500 a night and light lunches. No alcohol is served.

The children, who are brought to the ministry from the Swazi welfare society, stay in houses with a caregiver. There are approximately six children in each house. Last year Unicef estimated that the number of Aids orphans in Swaziland stood at 78 000.

“The damage will continue long after the child has left,” said Dr Jim te Water Naude, a Cape-Town-based medical specialist in public health and a member of the Asbestos Relief Trust (ART). The trust arose from an out-of-court settlement agreement between asbestos miners such as Gencor, African Chrysotile Asbestos Limited and Hanova Mining Holdings, and several claimants who had fallen ill with asbestos-related diseases. The ART helped to evaluate claims and provide adequate compensation for stricken former mine employees.

Least toxic

Chrysotile is claimed by many to be the least toxic type of asbestos, but the jury has been out on this for decades. Scientists and experts tend to fall into two distinct groups – those who believe it is almost harmless to work with, as long as certain procedures (including wearing protective clothing and close-fitting masks) are followed, and those who say even minimal environmental exposure puts residents at risk of lung diseases including asbestosis, lung cancer and mesothelioma. The latter two are almost certain death sentences, resulting from malignant growths in the lining of the lungs.

Asked whether he would ever live in Bulembu, Te Water Naude responded with an emphatic “no”. Although chrysotile asbestos has the least relative toxicity of the six types of the fibre, “all asbestos is carcinogenic”, he said. Bulembu Ministries’s former director Richard le Roux responded: “ART needs to say this to justify their existence.”

Asbestos stones on a dump in Bulembu, south of Barberton.

Bulembu Ministries has had air tests conducted three times since June 2012 by Ergosaf, a South African division of United States-based LexisNexis, which does risk assessments for governments and private industries, among other things. The results of the tests showed levels of 0.01 fibres/ml of air, but according to Naude the international standard is half that, and in Australia it is zero. (See correction below)

Dr Samuel Magagula, director of the ministry of health in Swaziland, said the issue of potential asbestos-related danger to residents of Bulembu has never been raised in Parliament. “It has never been brought to our attention,” he said.

No policy

Swaziland has no policy on the limits of environmental asbestos, according to Magagula, but he said if a policy was implemented it would be guided by the World Health Organisation.

Dr Kevin Makadzange, health promotion officer at the World Health Organisation’s Swaziland office, said the United Nations’s asbestos limit is zero. Academic papers from around the world concur that there is no safe level of asbestos.

Unlike the Msauli asbestos mine across the border in South Africa, there has been no attempt to rehabilitate the dumps at Bulembu.

Piet van Zyl, an Asbestos Relief Trust trustee and a career asbestos miner, said he would not have advised the ministry to establish the orphanage in a town like Bulembu.

“I would have hesitated bringing kids there [but] it was a logical place to use,” because of the existing infrastructure. Of the controversy about chrysotile causing mesothelioma, he said: “I’m not saying it’s safe, but you’d have to breathe in a helluva lot to get [mesotheliomia from chrysotile].” But Te Water Naude says there is no doubt chrysotile causes lung cancer and asbestosis.

“The children must just be educated about where they can go and what the dangers are,” Van Zyl said. “They must be told what can happen if they play in contaminated areas. [Management] must not let them near the dumps or any of the structures that might contain asbestos.”

Rehabilitated mines

Van Zyl worked for many years for the African Chrysotile Asbestos company at the Msauli mine, 5km across the border in South Africa. Although Msauli was the bigger of the two mines, it appears smaller and is harder to see on Google Maps.

Van Zyl says this is because it is covered with vegetation, having been extensively rehabilitated. He said the levels of environmental asbestos are practically zero in that area.

It has extensive infrastructure, but Msauli is almost completely abandoned, despite efforts to make it a tourist resort. “People won’t come near it when they hear it is an asbestos mine,” Van Zyl said. “You would never find Americans there.”

It’s not a bad thing: “We don’t want it to be disturbed. Nobody should be there in case they cause damage to the dumps and expose the asbestos again.” (See correction below)

Bulembu is currently working with the Swaziland Environmental Authority to find a way forward to raise the necessary funding to do so.

Bulembu Ministries has raised sharp objections to an earlier version of this report, and on the advice of the M&G’s Ombud, some additions were made on December 10 2014:

- After the paragraph dealing with measurement, the following: “Bulembu Ministries says the measurement at most sites revealed no asbestos in the air at all. At just two sites, low levels were found, which are however well below the level of 0.1 fibres / ml of air that is the limit accepted in SA law. Swaziland does not have its own legal limit, but follows the South African approach.”

- After the paragraph referring to rehabilitation: “Bulembu Ministries says it has spent about R 4-million contouring the tailings to prevent erosion and has covered about 2 hectares with organic matter to promote plant growth. This was done under the supervision of a firm of Canadian Consulting Engineers. A complete rehabilitation would cost in the region of R70-R100 million. The responsibility, and any associated liability, of the mine tailings lies with the Government of Swaziland. Bulembu is currently working with the Swaziland Environmental Authority to find a way forward to raise the necessary funding to do so.”

- After the reference to the price: “CORRECTION: Bulembu Ministries has pointed out that this was for a share in the property-holding company.”