The road is notorius for serious accidents. A bus accident in 2010 also claimed 20 lives.

This is ridiculous. It really is. How can one stay in a place and only know just the 700m or so radius within which one stays? It is madness, but crazier things have happened.

To wit, I live in the old East Rand township of Tsakane. I stay on one of the two main arteries here, the name of which is Ndabezitha, and it starts from the beginning, or what used to be the beginning, of what used to be the end of this township. It is a long road, even if they call it a street.

Convenience is everywhere; there is Malik on the corner of Ndabezitha and Ndawande, who sells me bread and beer on the sly. The library, which admittedly is not well equipped but serves some purpose, is a stone’s throw away. The pharmacy is also just here for my urgent needs. Meaning I don’t have to go far for a lot of things.

But the point of all this is not me but the people I share this space and time with, which is a hell of a space and time we are talking about.

Which makes me think: What was the struggle about? For people to continue to struggle? Sometimes I wonder what makes us hate each other as brethren, black brethren for that matter. Or is it perhaps that I am naïve?

These are things I consider as I venture out beyond my 700m radius, to a place called Extension Six.

Peculiar visit

My reason for this visit is kind of peculiar. I have heard that there are people who still use bucket toilets here. This shocks and does not shock me, for this is the kind of thing that can and cannot happen in the “new” South Africa.

Just three years ago, in the run-up to local government elections, residents of informal settlements in townships – like Khayelitsha in Cape Town, for instance – took to the streets to protest against unenclosed toilets, and, in some cases, the continued use of the bucket system.

This, despite the City of Cape Town having received R824-million for the 2011-2012 financial year from the Urban Settlement Development Grant to fix this very problem, according to the department of human settlements. A further R935-million was requested for the 2012-2013 financial year.

Piles of rubbish surround Tsakane Extension Six. (Photos: Madelene Cronje, M&G)

But still, the South African Human Rights Commission commented last year that “in the Western Cape, thousands of residents in various informal settlements across the province have no proper access to water and sanitation. [There] remains a high number of households, mostly in rural areas and townships, that continue to use the bucket system or remain without access to adequate sanitation services”.

But the bucket system here in my backyard? Really?

Is section 24 of the Bill of Rights in our Constitution – which insists that everyone has the right to an environment that is not harmful to their health or wellbeing – being wilfully violated?

Impassable road

The first thing you notice, as you enter Extension Six, is that the road, or whatever they call it, is almost impassable. But we hesh (as they say in the township, meaning “hustle”) in our small car, to get around. But the going is not easy. There are furrows here and there from soil erosion. There are stones, small boulders even, that really make driving here a pernicious exercise.

Betty Magaritsa is the first person I meet. She has been living in Extension Six since 2002, having come from Limpopo for economic reasons, which is itself a cruel irony given her current circumstances.

Living in parts of Tsakane means pit toilets and the bucket system.

The reason I stop to talk to her is that I see a small child come to get some water from a tap outside her home – which is a shack, but not especially shabby, whatever that means. But it turns out that this is not her tap alone; it is communal. “We had to gazat for this tap,” she tells me in our local tongue. Gazat means to club together.

” Gazat?” I ask.

“Yes, because if we had to wait for government, we would not have water, which is why we decided to gazat, and haul water from the people who have it on that other side.”

The other side is where people with RDP houses live and have access to running water.

‘Fallen’ toilet

As I speak to her, she also mentions that her toilet has “fallen”.

Hau, what do you mean, I ask.

“It has fallen,” she says, pointing at some structure that looks like it once was useful. Then I get her: she once had a toilet, but it was what is called in some quarters a pit latrine. According to the World Health Organisation’s website, this is the cheapest and most basic form of sanitation you can get and comes with a “seat or a squat hole” and “can produce unpleasant odours and allows flies to breed easily”.

“Now we have to get somebody to dig us a hole in the ground so that we can have another toilet,” says this woman of 47, who seems much older than the age she gives – poverty and stress, from suffering, do that to a person.

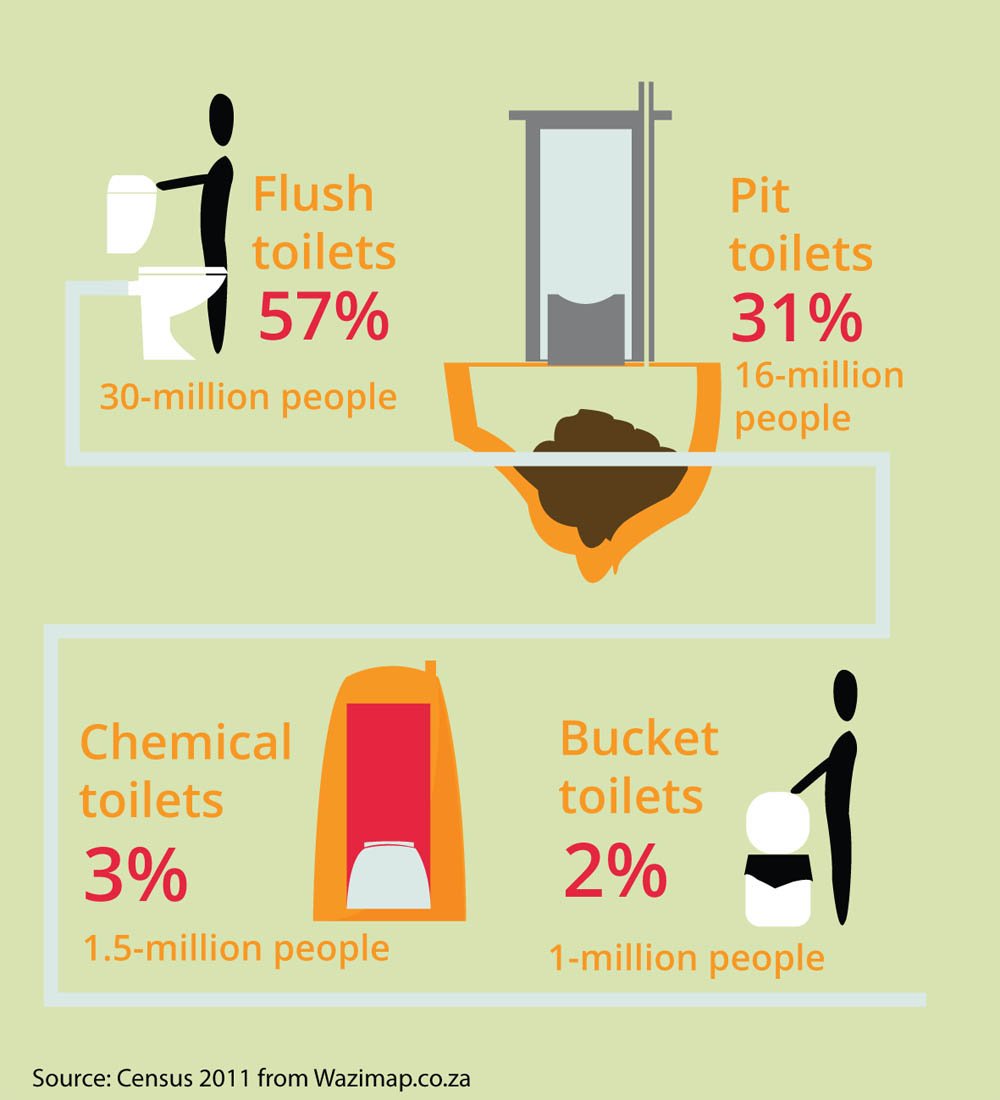

Without her pit latrine, she must use the bucket system, meaning she forms part of the 11% of formal and informal South African households without government-supported sanitation services, according to government’s 2012 Report on the Status of Sanitation Services in South Africa. They either use the bucket system, the pit latrine – or they just openly defecate.

Better than a bucket

Some of us buy a bottle of wine for R150 without so much as blinking, just so that we can have something to wash down that juicy steak with, after a well-prepared meal. But this woman, this mother of three, has to part with that kind of money so that some guy can come and dig a hole in the ground, which will be called a toilet, though it isn’t really, so she can relieve herself in a structure that is still not proper sanitation but must at least be better than a bucket.

I continue on my journey. I meet a girl coming home from school. Her name is Mathapelo Tsheoga (18). Although her school is nearby, at her home down the road there is no electricity, no running water, no refuse removal service and no flushing toilet, obviously.

Betty Magaritsa is not expecting service delivery from the government any time soon.

There is a lot of crime in the area, where rubbish is dumped in heaps, she says, but thankfully the police are quick to respond when you call. But call for an ambulance? “Ah, you are dead,” she says.

It is madness. And the councillor of Ward 81, for that is where Extension Six lies, as I am told many times on my journey, can’t be bothered, even though he was active in campaigning for the ANC in the last elections.

‘Health hazard’

I meet Nelisiwe Mthembu. She is from Mvela, another section of Extension Six. She, too, has been there since 2002. “We have long-drop toilets,” she tells me of her pit latrine, “but other people use the bucket system, which is a health hazard.”

Indeed. Buckets are sometimes not collected for days, which results in not only a terrible stench, but also the kind of big, dark green flies that always spell danger.

And when you combine this with the lack of water, you get diseases such as cholera, giardiasis and diarrhoea which, according to a 2002 state of the environment study of the North West province, accounted for nearly 30% of the burden of childhood communicable diseases in the province.

There is no electricity, no running water, no refuse removal service and no flushing toilet, obviously.

There is also the question of violence. In its 2014 report dedicated primarily to six-year-old Michael Komape from Chebeng village in Limpopo, who fell into a pit toilet at his school and died tragically in February 2014, the Human Rights Commission found that many women who are forced to relieve themselves in the open veld are often potential victims to crimes of rape and worse.

“The problem in the shanties,” said one resident to the commission, “[is that] we need toilets at every household because some of our elderly people, especially women, are raped at night.”

But who are these people who supposedly are working for this local community? And who are they accountable to? Whose struggle was it, by the way?

Informal settlements

I phone the councillor for Extension Six, Mthumeleni Ndita, to ask. He says the area has 1 300 officially allocated plots on which a lot of RDP houses have already been built. “But the problem is that we have an informal settlement of plus-minus 2 000 homes, and they have no electricity, that is true, and no toilets, not even chemical toilets.”

Ndita, also a resident of Extension Six, says he is acutely aware of the huge problems facing the majority of the residents. Which is why, on June 19 2012, angry service delivery protestors burnt his car and set his house on fire, he tells me. This, despite having reassured them that there was a developmental plan in place and that they only had to be a little patient.

“For instance, we are beginning to address the issue of electricity. Next will be the issue of water – for now there are government-supplied communal taps here and there – and proper toilets that flush. People must just be patient,” says Ndita, almost pleadingly. How long they will remain patient, though, is the R250-million question.

Tiisetso Makube is a writer and poet based in Johannesburg.