Writer Bongani Madondo in the remains of the family home in Pretoria where he grew up.

The Great Gatsbys we weren’t. Nor were we the Motsepes, the Ramaphosas or even the Zumas of the time, although you wouldn’t tell by the way my family keeps on droning on about our “oh so glorious” classy past.

Classy? Sure. Class? Mmm, needs qualification.

Look, what I partly mean is that although the family could be considered “old money” at any time, the entire Madondo clan could not even afford to make a down payment on a buffalo. Would they be even keen to do that? Well, that’s the thing … and the question of what we regarded as class sneaks in right there.

For years, my family – the book-loving, upper-cased and self-reverentially named, generations before mine, “The Madondos” – occupied a weird but exciting space revolving around some kind of lofty social status, going back aeons to the Natal Midlands, from where they trace their roots.

Or so rumour has it.

Secret vaults

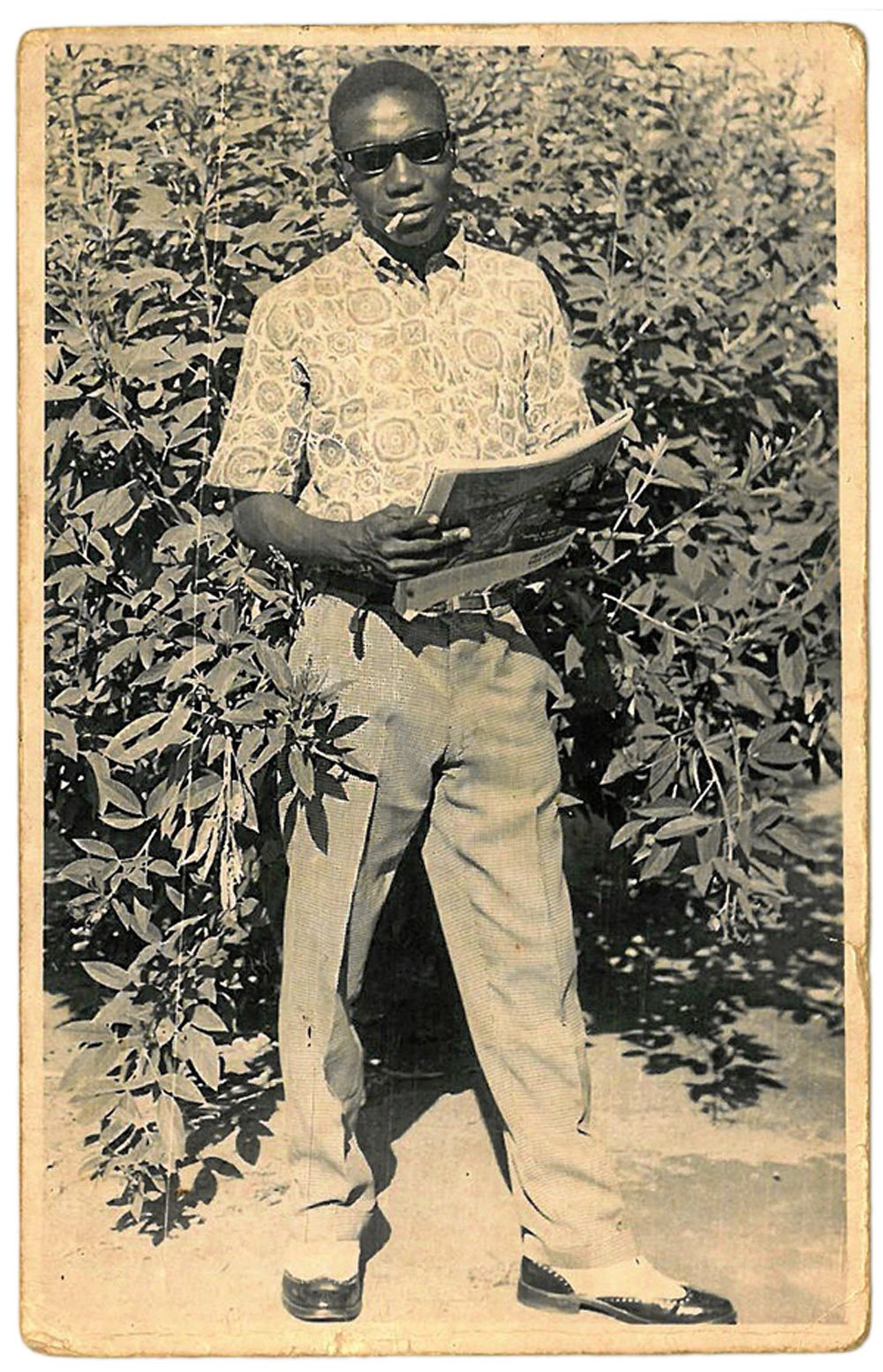

I grew up researching my family, yanking the lids off its secret vaults, paging through tattered photo archives, mostly stored in this or that granny’s gold-embossed vanity case, the family’s storage vault for heirlooms – including real and faux gemstones, not to mention the pearl pieces I have only spied around the necks of Hollywood society dames of the sepia era. I have grown to (dis)trust, digest, internalise and ultimately play out a variety of roles from my ongoing family’s doccie-thriller of a life.

Those roles – from piano lessons to being accoutred in tweeds and button-down long sleeves, just like the British brats in Brideshead Revisited – of course came with a flood of “whys” about why my family was the way it was.

For instance, why do we hold ourselves in this way and not that way? Why does such-and-such granny hold her cigarette or teacup in the way she does? Why are we obsessed with land? Why did we build double-storeys on those pieces of real estate whenever we found ourselves?

I just couldn’t get it.

Why do we, not so unsubtly, tend to turn our backs on anything we don’t understand and have, almost by DNA, decreed it déclassé? Most importantly, why do we love harking back to the past?

But also, if we were and are all that, why is the family now reduced to a bunch of generational alcoholics?

‘Well brought up’

I have not had direct answers to these questions, save the most spoken-about narrative, which starts and ends with one word: ukufunda. We assume, sometimes with no proof or certification, that sifundile (and, in some cases, sifundisiwe) – is a variation, if you will, of “we’ve been well brought up”.

Now the attributes and virtues attached to it might not, at face value, have anything to do with what my family has always prized as their class entry point and signifier – a love of books. But somehow, in the late 19th and early 20th century, African middle-class logic and manners (or assumptions of them) have always been associated with ukufunda.

It’s why in places such as the Eastern Cape there has always been a belief that the one thing defining the difference between the so-called amaqaba (red-blanket nativists who prize African spirituality over the white man’s “God”) and amagqoboka (presumed Westernised Africans) is that the latter are book people and the former are the great unwashed at the gates of civilisation.

It is not necessarily good or bad manners that distinguish one from the other, but assumptions that learned people would be more well mannered and thus predisposed to civilisation on the white man’s terms, as opposed to those who rejected Western intrusion.

Of course, all those are missionary and colonial holdovers, but a great majority of the African middle class and landed gentry are nothing but developed clones of a certain aspect of Western limitations of civilisations, aesthetics, beliefs and economic models – and I speak as an heir of such people and practices.

Book wealth

My family has always prized its book wealth over its material fortunes, although that sort of book worldliness has, for some decades, given off a lovely faux sense of “arrival”. That we, too, have arrived. That we, too, matter.

So where did this love for books and its confusion with material wealth come from?

This much I can testify: the family generation I was born into had, in the 1970s, made the semirural, semiurban enclave of Hammanskraal, north of Pretoria, its home.

Busisiwe Madondo, one of the ’28 Sisters’ of the Madondo girls in Eastwood, Pretoria, 1940s.

Different splinters of this once majestic clan spread themselves like wild berries across the wide sweep of Hammanskraal, some in the township of Temba, some in the tribal settlement of Kekanastad. Others planted seeds where I grew up in Leboneng, meaning “a place of light”, the first truly upper-class African suburb in the region to have street lights, children studying at Oxford and the University of the Witwatersrand, and mansions peopled by Old Money Society.

Although it pains my family, even now, the fact is that by the time my eyes were wide open enough for me to start asking questions, my family was not what it used to be. Or what it used to imagine itself to be: “The Madondos” were partly a figment of our imagination.

They might have been important once but, even then, what level of importance? But that’s the story we’ll get to pretty soon.

Books everywhere

Books and loving books are what defined my generation and those before. At any of my relatives’ homes – many of which sold African-brewed beer – there would be books carpeting every nook and cranny. Often there were no bookshelves, let alone much furniture, but books were scattered everywhere.

In my mom’s part of the mansion where we grew up at the patriarch Reverend “Oupa” Morudu’s place, you could find them on the wardrobe shelves and under the beds – the place was filled with books of all kinds.

My Uncle Sipho would derail my home entertainment of reading what passed for as the classics, like Chaucer, Coleridge, Shaw and Shakespeare, and the series of brown leather-covered Encyclopaedia Britannica; strangely missing was the African Writers Series, at least in my prepubescent years. But alongside those DOBs (dead ol’ British men) were what we later learned were the “white liberals” (although slap me if I knew what “white liberals” meant before reading that Biko oke): Alan Paton, Laurens van der Post, Nadine Gordimer and Donald Woods fought for space in the family’s poorly archived book collection.

“Codswallop,” Uncle Sipho would say. “The greatest literature ever written are the comics, I tell ya.”

“Could that be true?” I ran to mom, panting. “Are the comics the best stories ever told?”

Instead, Dear Bishop caught a whiff of it and waved me off in that way old people do. “It’s because your uncle, hili qaba [is uneducated].”

Philosophical junk

He could have fooled me! Sure, maybe my uncle lacked the missionary education of his forebears. But what he ushered me into was an entertaining world of witty, street, deep and philosophical junk and wisdom that I have yet to emerge from several decades later. Under his tutelage, we binged on a vast array of the best comic-lit ever published in the world: Archie and Veronica, Jughead, Mad comics, Casper the Friendly Ghost.

Even my dude Tin-Tin was there, although I later learned the little Belgian twerp, or hero, was a friggin’ racist, but back then we had no inclination what stock the word carried in its dullness. What we knew “fo’ sho” was that the boy with a pre-punk mohawk was beyond cool. Not Superman cool. Neither Batman hip. But just as adventurously diffident.

It wouldn’t be long before we graduated to pulp fiction and my uncle’s stash of sleaze-lit: James Hadley Chase, Mickey Spillane and Mario Puzo. Of course, the elders in the family insisted that for every sleaze we binged on we had to read two English classics, as though to cleanse the smell of Chase’s dead blonde bodies found with caking wounds, with a smoking gun in a poor toff’s hands.

The adults, of course, binged on theology, the Bible and texts by the likes of the American radical theologian Reinhold Niebuhr and the great tales of the African-American underground railroad heroes and heroines of the Jim Crow era.

Sometimes I suspect this culture of books and burying ourselves in between the pages is responsible for the lack of social skills in the family. To this day, it is not unusual for us to greet one another with the inquiry: “What are you reading?” whenever we meet, even before asking about children’s health and such mundanities that pass for manners.

Man of few words

My younger brother is in jail – and has been in the dungeon for a stretch. He’s a man of few words. In fact, “few” is a tad too much. His icebreaker whenever a family member pays him a visit goes something like this:

“Um, ah-mm. So?”

“So what?”

“How many books have you brought me?”

“Um, that? Five. That’s all the correctional services allows.”

And then he lets out a thin, inaudible whine: “Only fi-i-ive?”

A wedding photo of Bongani Madondo’s grandfather and grandmother.

Walter’s opium is the biographical form. Especially the memoirs of heroic African-American young men in chocolate cities right across the United States, beating the system through old virtues of tough love, tough work and tough streets, going on to philosophise about their transitioning from the projects into the American Dream.

His ideal book has only been suggested, never mastered. That would be a mash-up of Biggie Smalls and Cornel West. Maybe he has never heard of Chester Himes. (I make a mental note to order him Chester Himes but I never get around to it.)

Home library

Walter will be up for parole sometime soon. But the family is less worried about helping get him a job in order to convince the parole board of his fitness to be released, and more concerned that we have not built up a home library big enough for his taste when he steps out of the hole.

Wait! This hardly explains the clan’s class obsession, does it?

Look, we were not immune to material wealth and the status that it brought, or vice versa. What we were immune to is the now all-too-common belief that material wealth on its own equals class.

“Honey, no amount of dweesh can purchase you class. Ay, nah, sweet cakes,” said Edith “Koppotjie” Madondo, one among my grannies who worked in the house staff of old white South Africa’s first state president CR “Blackie” Swart, when not running her side enterprise as a designer and a shebeen queen.

Although they were and are still petty much obsessed with class – theirs, compared to everyone else’s. Which could be the reason why some, like yours truly, display a kind of residual, misplaced sense of superiority. My family’s biggest “status” obsession in my grandma’s and mom’s generations centred less on the material than on intellectual curiosity.

Class and pride prejudice

But the story of “The Madondos” and their current class and pride prejudice stretches back to the rural idyll of KwaZulu – Alan Paton land. It can be traced to their arrival in the, multicultural, New-Afrikans’ freehold settlement of Eastwood, just east of Pretoria.

It is said that, at the beginning of the 1920s and at the end of F Scott Fitzgerald’s much-romanticised jazz age, my family’s grand patriarch, William, his wife Rhoda and a few of their offspring arrived in Pretoria direct from Glencoe in the Natal Midlands to work for the state iron ore and steel mega-parastatal, Iscor (now ArcelorMittal).

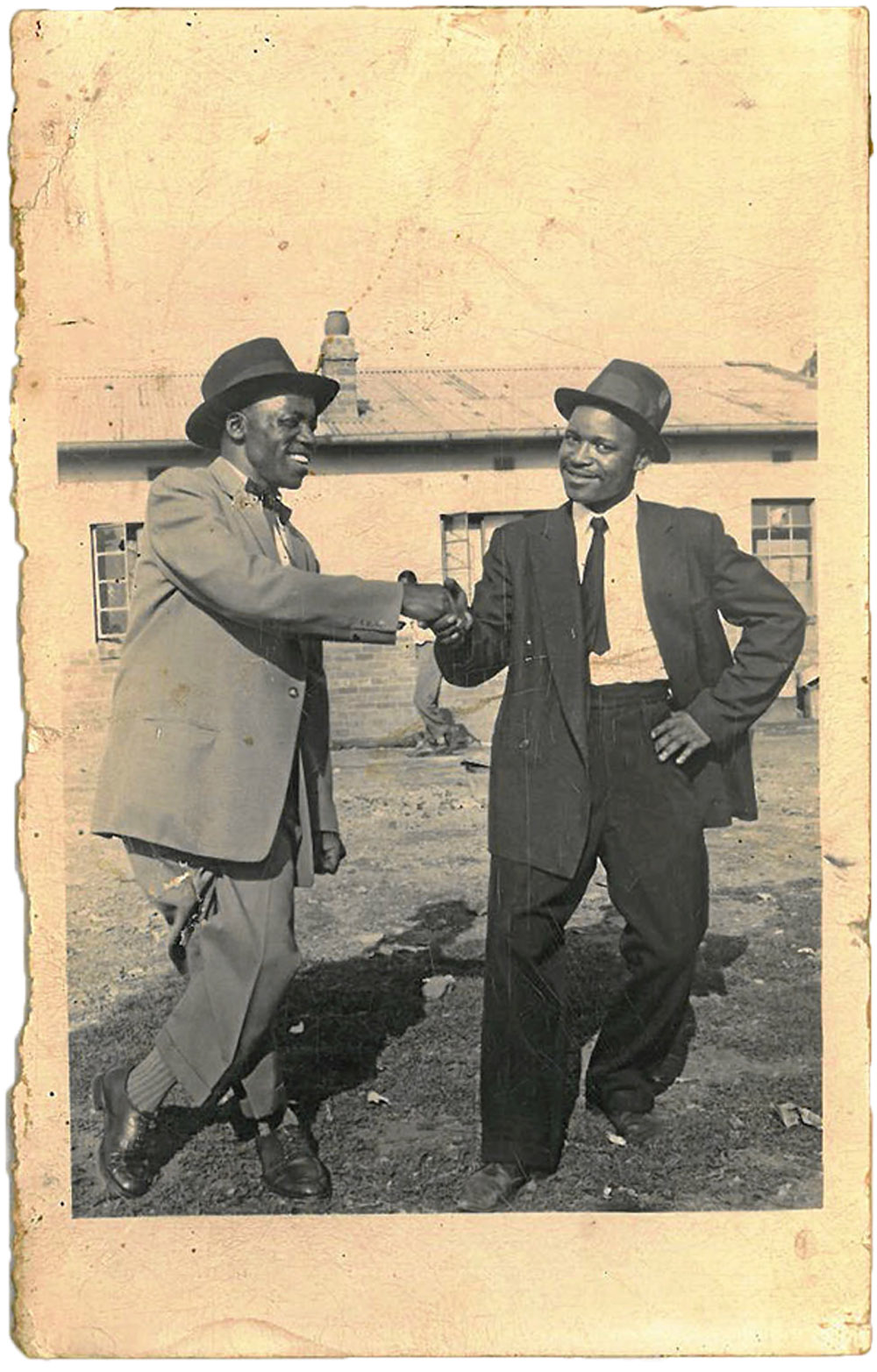

Ireland Madondo, a professional golfer on first name basis with Gary Player, with a friend.

The mythology is that William’s grandfather worked as a “bones man” (healer), and the equal of the modern-day artisan and engineer, in the conquering Shaka Zulu’s army. The story goes that both creativity – working with your hands to sculpt anything of your fancy – and medicine, or healing rather, runs in our blood, though for a while it felt that booze did so more than those gifts.

Like his dad, whom nobody calls by anything other than the clan name, uMnquhe, he was a skilled ironsmith.

The Boers, who by then were already building their state’s industrial complex and seeking skilled and nonskilled native labourers, apparently acting on a tip-off from some industrialists or explorers in Natal, inquired about and finally recruited ol’ Bill to work for them at Iscor.

Blue-eyed boy

For the cattle he had to leave behind, they gave William oodles of hectares of land and built him the equal of a mansion in the early 1920s, and gave him the word he would be: the Special One. For a time, the Zulu gent was the blue-eyed boy. His address, as they say, spoke to that.

He arrived and settled in Eastwood. With its salt ‘n’ peppering of Indian, Chinese, African, Portuguese and coloured denizens, the area was, like Sophiatown, smack bang in the white man’s land. In fact, today its outskirts can be traced nearly to the further reaches of the eastern parts of the current Union Buildings, the heart of Brooklyn, the wing of Hatfield, down to Muckleneuk on the southeast of the current University of South Africa’s main campus. Then, as now, larney land!

His children were well cared for. The girls of the family – they called themselves the “28 sisters” although they were only five – didn’t have to do laundry or any household chores. Every whim and need was tended to by their staff of Malawian tailors, Rhodesian cooks and Portuguese grocers, who were all on call.

“We are The Madondos. Yeah, The Madondos. D’ya know what that means? Da ya?” This is the sort of line you often hear at my family’s gatherings, often coming out of the mouth of our dear inebriated Uncle Hope.

Every time those words tumble out of his mouth, everyone, especially the younger set – the misnamed born-frees – who never experienced the family’s “charming” past move uncomfortably in their seats.

Presumed specialness

We laugh nervously every time we hear that. We throw each other knowing winks. We pretend we are above that … bragging. But we are not. The inebriated uncle speaks to what is rooted deep in our DNA: our presumed specialness.

But the sooner that we get it through our thick skulls that we just aren’t that special any more, that the two generations before us squandered any hope of us being somebodies ever again, the better.

It doesn’t look like it, though. It looks as if our bruised pride is too huge, an ingrained genetic gift-curse that is not as easy to dismantle as that. We will not roll over and die.

My generation, and the ones hot on our heels, are impatient to restore the family glory. It is silent, it is intense, it is focused, it is clinical, it is super-ambitious and it is done with the sort of innocence that can only be inspired by revenge.

It is, in a twisted way, rebuilding at least a sense of pride. No true great success comes without a wee bit of bitterness. Ours is a revenge on the 1950s removals across the country and, more specifically, in Eastwood.

Smashed heritage

When the white man and his grey removal truck moved in, forcing whole African families out, without even considering whatever status and value they might have believed themselves to have, he did not grasp the extent of heritage, narrative and lineage he smashed down.

Fifteen of our family members, mostly women, were removed from their father’s mansion with its sprawling orchards, Buicks, Chryslers, servants, extended relatives, tenants and so on, and sardined into a four-roomed matchbox in the newly built township of Mamelodi East, 20km from Pretoria proper.

Loki Madondo.

Life in Mamelodi, or any other township in the land in fact, would never be as sweet and dreamy as life in the freehold settlements– even though some, like Sophiatown, were, in parts, the pits, never mind what the intellectual romantics say today.

It is in Mamelodi that The Madondos of relative wealth, grand ambitions and high self-esteem were humbled beyond their comprehension. The lustre went rusty. Their dignity took a nosedive.

This is the period I now look at in retrospect as marking the onset of alcoholism in my family … a psychic reaction, if any, to being reduced from a family in the manor to servants, hustlers and complainants.

Confining by design

The confining design of matchboxes with their rooms, little more than prison or old army barracks cells, would be looked at by the more realistic and politically sussed architects and sociologists as the apartheid engineers’ genius in cutting the self-regard of the first wave of urbanised African bourgeoisie down to size.

Although there was no escaping the omnipresence of money as a shaping force in my family, books are what actually grounded us, from my mom’s generation onwards. We have come this far. We have been wounded. Spirits trampled upon.

Bloke Modisane, one of the exiled Drum scribes, once observed, rather ruefully, in the opening gambit of his heart-aching memoir of class aspiration, jazz, baroque music, Mozart, Debussy, Chopin, classical literature, white bohemians paying fealty to “black men about town” in Sophiatown and life at Drum magazine: “Something in me died, a piece of me died, with the dying of Sophiatown. It was in the winter of 1958, the sky was a cold blue veil …”

Aw, Blokey! Handkerchief, please.

But dear Bloke, do I have news for you. In several of my sporadic visits back to Hammanskraal, I’m animated by a sense of renewal that’s so intense, it’s electrifying.

And, yes, the current crop have all reawakened to the transcendental wealth and possibility books can gift you. But, like you, I’m not sure of our place in the current bling-class milieu.

Bongani Madondo is a cultural and social critic. His latest book about Brenda Fassie, I’m Not Your Weekend Special, an edited anthology, was recently released by Pan Macmillan. He is currently working on a monograph about Cyril Ramaphosa.