Joey, the star of the theatre production War Horse, matches the appearance, in stature and mannerisms, of a live horse. When he breathes into the crowd, a thick-winded grunting and equine-like gurgling amaze the audience at Montecasino’s piazza in Fourways.

The production, an adaptation of the 1982 novel by Michael Morpurgo, centres on a young boy whose horse is taken into service by the British army during World War I. Having premiered at London’s National Theatre in 2007, War Horse is finally touring Johannesburg and Cape Town from October 22. This is truly an intricate production. Up close, the realistic wonder that is Joey is revealed to be a frame covered in a thin transparent cloth that resembles skin.

Three puppeteers skilfully manipulate his movements. One operates Joey’s head from outside the horse’s body, moving his head, neck and ears with a control stick. The two other puppeteers, partly obscured inside Joey’s body, manoeuvre his front legs and breath with a lever and handle and his back legs and tail with ski pole-like rods. The 2.5m puppet, weighing in at 43kg, has an aluminium spine and a body made of cane, leather and Tyvec fabric (a synthetic material).

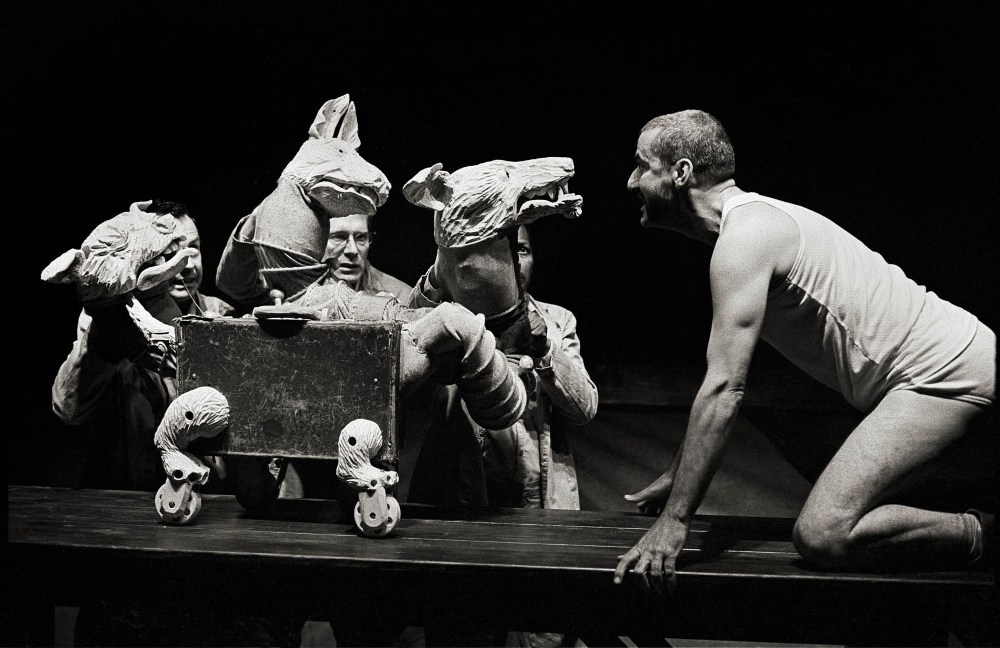

Joey, alongside the other life-sized puppets in War Horse, is the creation of the Handspring Puppet Company, which was co-founded by South Africans Adrian Kohler (artistic director) and Basil Jones (executive producer). Considered to be a world leader in the puppetry field, the Cape Town-based company has built an enterprise that has created a number of jobs for local puppeteers and artisans. When Handspring arrived on the scene in the 1980s, it revolutionised a market whose main exposure to puppetry had been through children’s television shows such as Liewe Heksie, Pumpkin Patch, Mina Moo en Kie and Mulwana la Mmutla.

The company’s first play for adults was Episodes of an Easter Rising in 1985, a string puppet adaptation of a radio play by David Lytton. The company has since gone on to produce many more plays using puppets, garnering accolades along the way. War Horse’s London and Broadway runs scooped many awards, including a special Tony Award for Kohler and Jones. The reaction of the audience watching, wide-eyed in terror or curiosity, the undulatory movements of Joey at Montecasino’s Teatro is an indication that the production will no doubt shine the spotlight on the under -estimated skill of puppetry.

Puppetry in the classroom

Kohler says that, when he started out, people often asked him: What kind of a career is puppetry for a grown man? Forced to choose sculpting as his art school major because of the lack of specialised puppetry programmes offered at tertiary level, Kohler went on to the Space Theatre. Stellenbosch University’s drama department is still the only place in the country that offers puppetry as a specialisation, albeit one that is dependent on the number of enrolments for the course. The Tshwane University of Technology offers a course in stage props and puppet-making.

The Handspring Trust also offers puppetry training sessions. The South African Association of Puppetry and Visual Performance in Cape Town runs mentorship programmes and occasionally hosts puppetry workshops for the public. Puppeteer Cindy Mkaza-Siboto, the operations manager of the association’s active puppets programme, says the organisation helps to develop puppeteers and works with theatre groups. It trains about 20 puppeteers a year; the local market is too small to sustain more than that.

Students can enrol for a yearlong skills development programme, which includes lessons in set design and puppetry. “People need education about what puppetry is. There are still people who assume puppetry is for kids,” she says. But more and more theatre-makers are looking to puppetry to appeal to the masses. Mkaza-Siboto has noticed a trend for companies to use puppets as part of their marketing strategies. “Companies are attracted to puppetry because it’s a flexible art form; you can make things bigger and larger than life with puppetry.”

Pulling the right strings

Businesses may be gravitating towards puppetry to sell their products, but few are investing in the industry. One of the biggest puppetry and visual theatre festivals on African soil, Out the Box, was cancelled in 2012 and 2013 because of limited funds. The Cape Town-based festival is a platform for puppet enthusiasts to learn more about the art form through talks, exhibitions, street performances and workshops tailored for adults and children. This year, Out the Box was hosted under the umbrella of the inaugural Cape Town Fringe Festival in late September and early October.

“The government doesn’t want to fund a festival. They would rather fund developmental projects. The artists have been sad about it [the cancellation of Out the Box as a stand-alone event], but there is not much anyone can do,” says Mkaza-Siboto. The National Lottery Distribution Trust Fund and the Arts and Culture Trust were among the sponsors of previous Out the Box festivals. According to the Cape Town Fringe Festival website, it made sense for the organisers of the puppet festival to partner with the fringe because of the bigger platform and resources it could offer.

The 2010 Standard Bank Young Artist winner and Out the Box director, Janni Younge, said the turnout for this year’s festival was poor. Younge attributes the low attendance to the Cape Town Fringe being a new festival and its collaboration with Out the Box being a learn-as-you-go experience. “It is not easy to put together a festival and we hope next year will be bigger,” says Younge, who was the associate director at Handspring and chief executive of the puppetry association. She has also created puppetry and masks for brands, such as ZA News and the Royal Shakespeare Company. “We [South Africans] produce the best puppetry in the world – not necessarily for South Africa but for the world,” says Younge.

She laughs at the idea of Cape Town being the country’s puppetry capital, but acknowledges that most large puppet companies are based in there. “There are some great puppeteers in Johannesburg, but I think they are less vocal about what they do.” South Africa’s puppetry tradition is not a recent phenomenon. Before puppetry found its place inside the walls of theatres, masks and figurines had long been used in rituals and traditional ceremonies. It was the influence of European puppeteers visiting the Cape Colony in the 19th century that shaped and entrenched South Africa’s puppet theatre traditions.

The pioneers of the art form

Gawie de Wet, South Africa’s first post-colonial professional black puppeteer, is hailed by Handspring as one of the first teachers to use puppetry as an educational medium. This was in the 1950s. He used his primitive carved puppets to tell stories in his community. Later, this pioneering puppeteer from Beaufort West decided to incorporate music into his puppet shows and performed at school concerts and agricultural shows. Farmer-turned-puppeteer John Wright is another significant South African. His first performances, according to the Camden New Journal, were in an old farmhouse. Wright added local flavour to his puppet shows by featuring Cape Malay characters and songs.

Using marionettes (puppets controlled from above using wires or strings), he performed in several African countries and even on Broadway. In 1961 he opened the Little Angel Theatre in London, where he settled after 25 years of touring. Between the 1950s and 1970s, international puppet companies such as Wright’s shared their skills and know-ledge with aspiring local puppeteers. This boosted local amateur puppeteers and puppet companies. The first professional marionette company in the country, founded in 1968 by Michal Grobbelaar, was housed in the Johannesburg Civic Theatre (today the Joburg Theatre).

It is perhaps in large part thanks to Handspring’s rich collaboration with critically acclaimed contemporary artist and filmmaker William Kent-ridge that South African puppetry has become a vehicle for entertaining audiences with creative story -telling and social commentary. One of their first productions was 1992’s Woyzeck on the Highveld. Based on a work by German playwright Georg Büchner, the play incorporated animated film and puppeteers manipulating hand-carved wooden puppets to comment on the injustices experienced by migrant workers in Johannesburg’s mines. Other notable collaborations include Ubu and the Truth Commission, Faustus in Africa and Confessions of Zeno.

According to the puppetry association, job opportunities for South African puppeteers are on the rise. Artist Daniel Popper, a graduate of the Michaelis School of Fine Art, is a case in point. He created a giant puppet for the AfrikaBurn festival in the Tankwa Karoo in 2007 and, as a result, was commissioned by MTN to produce 14 more for fan fests around the country during the 2010 Fifa World Cup. The Giant Match Association from Orange Farm, a township just outside Johannesburg, and Roger Titley produced giant puppets for the World Cup’s opening ceremony and to entertain crowds at the various fan parks.

Puppeteer Sidwell Klaas believes there are many opportunities for young, up-and-coming puppeteers. “There are a lot of people looking for people who can create puppets for shows,” says Klaas, who, having trained with Handspring, now trains people in Khayelitsha in puppetry. His dream is to open his own puppetry school. “We need more schools that teach puppetry,” he says. Klaas was part of the puppet show Qhawe, which was staged at the recent Cape Town Fringe Festival. “Puppeteers need to create job opportunities for themselves. There isn’t a lot of money in theatre,” says Younge, who believes there is a great demand for puppetry in children’s theatre and in the field of social development.

For Younge, the local puppet industry is hamstrung by limited financial backing and infrastructure. Corporates are not jumping at the chance to finance puppet productions, an exception being Rand Merchant Bank, whose sponsorship is enabling War Horse to make its way to South Africa. “I wish more businesses would back excellent and edgy art productions,” says Younge. “People need to understand that investing in the arts pays off. In New York and London the arts form a great part of the country’s economy.”

Staging a high-end puppetry production is costly, she adds: just one puppet can cost R15?000. In the world of broadcasting, puppets have taken centre stage on comedy spoof shows Late Night News with Loyiso Gola and ZA News, with the focus being on political commentary. “People allow puppets to get away with a lot of things. I think that is why people like watching a show like ZA News,” the show’s Roshina Ratnam says. Ratnam was part of the team that put together the puppet show Elnora & Nirvana, another Cape Town Fringe production.

But even after working with ZA News, which has won three South African Film and Television Awards, Ratnam still gets asked: “So, do you play with dolls for a living?”

War Horse is on at the Montecasino Teatro from October 22 to November 30, before transferring to the Artscape Opera House in Cape Town from December 5 to January 4