?Inge Prins found pregnancy awkward. Her changing physique overrode other aspects of herself; it made her public in unexpected ways

Inge Prins found pregnancy awkward. Her changing physique overrode other aspects of herself; it made her public in unexpected ways, never mind affecting her chosen wardrobe. Always curious about what messages the clothing we wear communicates, she (semi-mutinously) began wondering what men would wear if pregnant and how they would adjust.

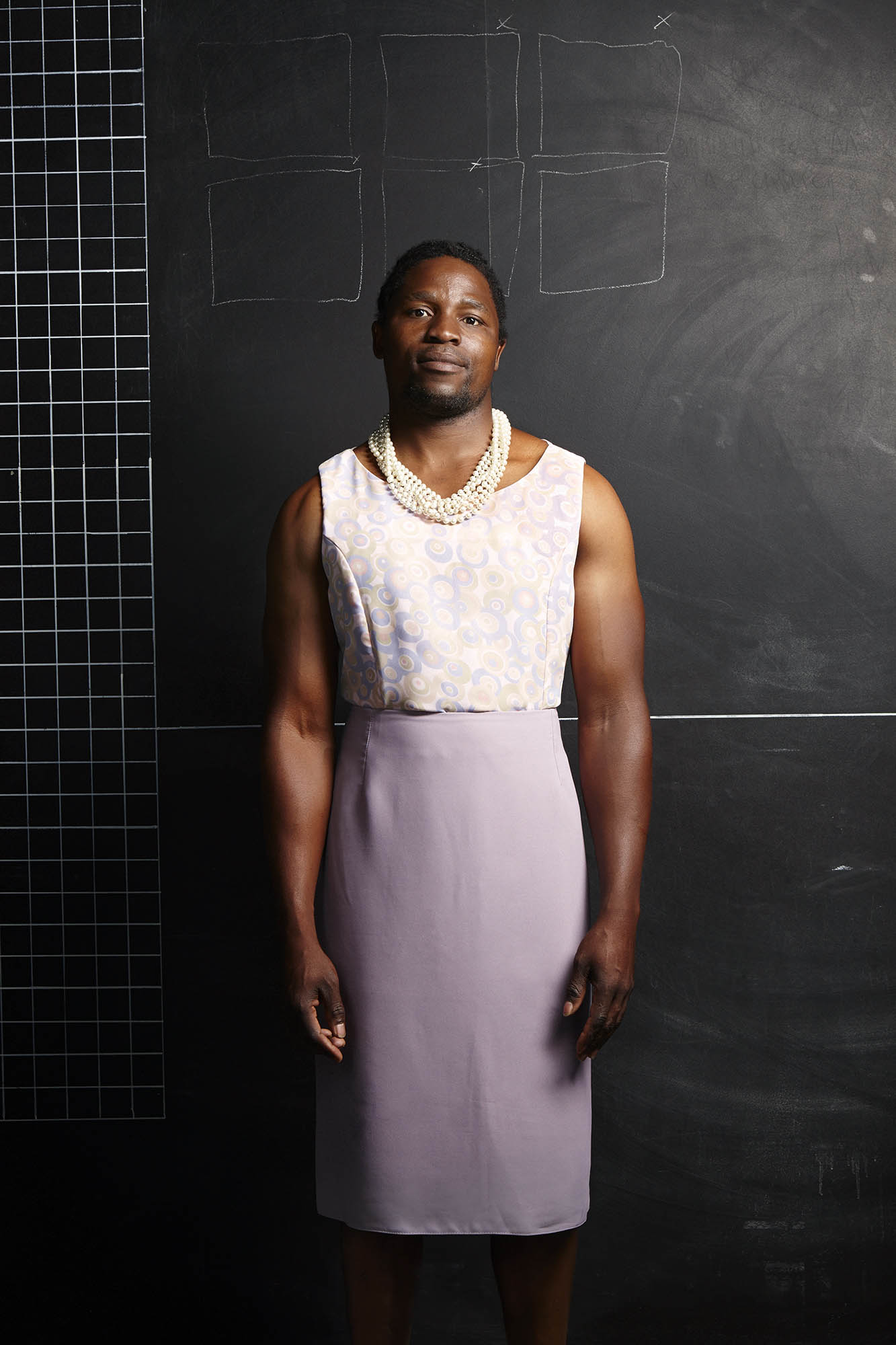

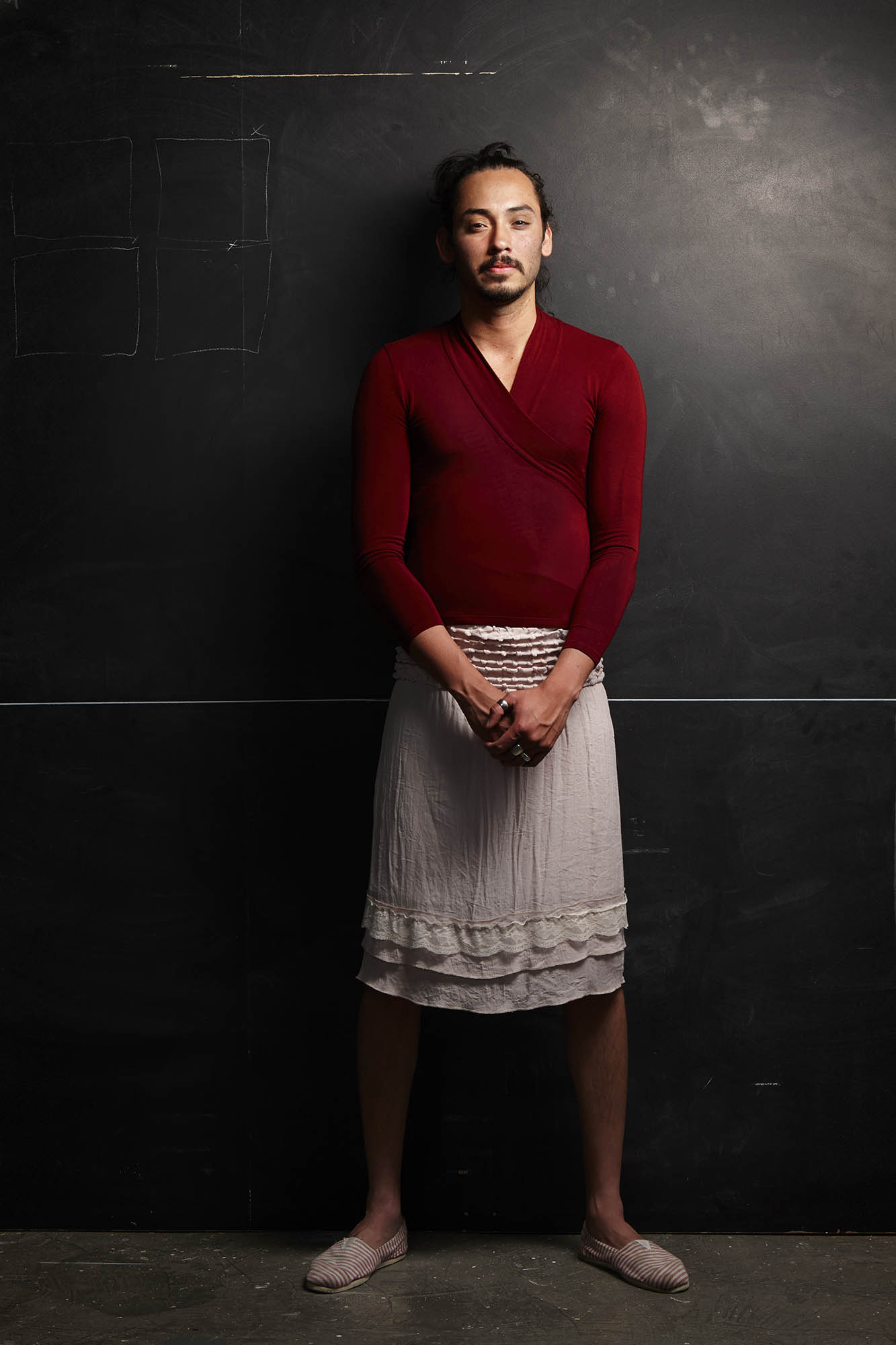

“It got me thinking about what men would look like in women’s clothing; as if the man had put on his wife’s clothes by accident. How would it sit? I even thought I’d put a fake belly in,” Prins says of her collection of 10 portraits of men dressed in unexceptional female garments, three of which are currently on show for the Cape Town Month of Photography.

As it turned out, Prins didn’t go the extra belly route: skirts, blouses and filmy fabrics proved enough to raise interesting questions.

Prins studied fine art at Rhodes University under renowned South African photographer Obie Oberholzer and works in the commercial world, shooting fashion, décor and interiors. An earlier solo project echoes her latest work: she shot elderly men in suits — to her the uniform of patriarchy — then draped them in jewellery to undermine the effect.

It was a reaction to her Afrikaans upbringing in Pretoria, to “that male dominant figure and my father specifically” (her father, who died at 89, had become far “softer”, “more in touch with his emotions” as he aged).

The Office Politics series is curious, but not in expected gender stereotyping ways. A man in a dress — in parts of Cape Town anyway — has little power to shock. Prins avoided the carnivalesque aspect of dressing up that is somehow more socially acceptable: sanctioned, exaggerated role-swapping. There was no make-up, no “fashionable” clothing.

“If it was fashion, I was worried that it would become more ‘drag’, that humour would take over. This isn’t about dressing up. I wanted it to be very neutral: the woman in the queue who has just left the house in what she was wearing.”

The pictures are strange. The men’s bodies pull and push at the seams. Fabric clings to bulges and bumps, stretches over bones. Skin looks peculiarly exposed, on display. The difference in physique (broader shoulders, bigger hands, longer arms) is not unexpected, but the female cut of the clothes does more than expose this truism.

“For the first time I realised how women’s clothing shows the female body,” Prins says. “Most male clothing isn’t cut to show the male figure — even T-shirts and pants are straight lines and shapes; their clothing is more like armour, whereas female clothing uses softer textiles, pleats and details to show off necks, shapes, shoulders and bums.”

The result was that the men looked “vulnerable”. Not because of the usual observation that female clothing restricts movement, but “because the clothing is more revealing, you’re aware of your shape”. Imperfections are displayed. Suddenly the male form can be compared to an ideal — and be found lacking.

The men are a hodgepodge of friends and acquaintances. They are photographers, film industry workers, product designers — on the whole more aware of gender issues. The most “masculine” of the friends found the assignment more amusing; they giggled and joked. Only one, assigned soft pants that clung to his crotch, was really uncomfortable. Another told of how he’d stood in front of his girlfriend’s wardrobe and thought about wearing her garments, but felt it was “too much”, that it would be “crossing a line”.

As Prins says, across wider South Africa, femininity in male dress can still be associated with homosexuality. “That’s very simplified and it is changing, but there is still that line,” Prins says. She didn’t plan to shock; in fact she didn’t think the pictures could shock contemporary South Africans.

Yet when one, a journalist, opened the pictures of him that she’d sent him in the office, a slightly older colleague “was so embarrassed he couldn’t even make eye contact”.

“The world is shifting,” Prins says. “Men’s bodies are definitely becoming more sexualised. But as a country, if you move out of the cities, there is still very much an old-fashioned, patriarchal, chauvinist [attitude in South Africa].” Here, suits and male clothing remain more armour than individual decoration.

Office Politics is on until October 30 at Youngblood, 70-72 Bree Street, Cape Town, where 18 photographers are showing work as part of the Cape Town Month of Photography.