South Africans should be wary about blowing their hard-earned cash this festive season – the taxman is coming.

Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene has all but promised that in February’s budget the public can expect the announcement of higher taxes.

To help to balance the government’s books, Nene aims to raise about R44-billion in additional tax in the next three years, according to the medium-term budget policy statement he delivered last week.

The treasury did not offer a hint about where the extra tax is likely to come from. But it will take its lead from the recommendations of the Davis tax committee, which are expected before the budget in February.

The committee was established last year to review South Africa’s tax.

Economists and tax experts have put forward several ways in which it could be done.

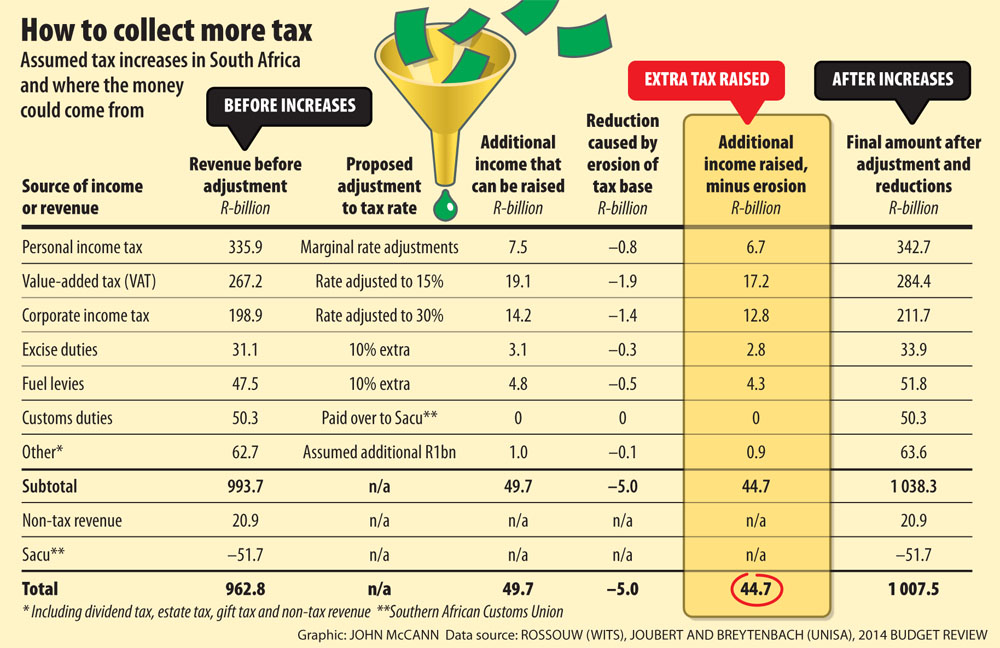

An analysis by Professor Jannie Rossouw, the head of the school of economic sciences at the University of the Witwatersrand, and Fanie Joubert and Adèle Breytenbach of Unisa’s department of economics, established that a combination of increases in personal income tax, company tax and value-added tax (VAT) could bring in the required R44-billion.

This is based on the assumption that R44-billion is the actual amount required. If the amount is in nominal terms and needs to be adjusted for inflation over the years, the funding need “increases considerably”, according to the research.

Assuming an inflation rate of 6% a year, the total funding needed would rise to R48.5-billion.

The creation of two additional marginal tax brackets for higher-income earners – 45% for taxable income above R1-million a year and 50% for taxable income above R2-million a year; an increase in the VAT rate from 14% to 15%; and an increase in companies tax from 28% to 30% could raise the additional funds, they note.

But they warn that the additional tax burden could erode the tax base and they factor in a 10% elasticity or reduction of the tax base as a result. For example, people could spend less because of increased VAT rates.

Nevertheless, accounting for this erosion, increases in private income tax, companies tax and VAT, along with 10% increases in fuel and excise duties, could bring the state an additional R44.7-billion, according to the research.

Cut expenditure

But the academics say tax increases shouldn’t be the preferred way to shore up the government’s finances. They call for bigger expenditure cuts, including a reduction in the size of Jacob Zuma’s Cabinet and a halt to the growth of the civil service.

According to the adjustment budget, the president’s latest restructuring of the Cabinet following the elections earlier this year cost South Africans an additional R65.7-million.

The academics have also argued in previous research, first published in the academic journal Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe, that, without curbing the growth of the civil service and the pace of increases in the public sector wage bill, the state will hit a fiscal cliff and be unable to sustain the government’s finances.

Nene did commit the government to curbing wage increases, freezing the government’s headcount and further reducing the government’s noninterest expenditure to 1.3% in real terms. The treasury pencilled in nominal increases of 6.6% in the government’s consolidated wage bill over the next three years.

Sticking to these proposals will be a test, though, because civil service unions have already been calling for a 15% wage hike.

In a statement earlier this week, the ratings agency Fitch described the treasury’s figure as “ambitious”.

“Expenditure projections are based on the ambitious assumption of public wages increasing only in line with CPI [consumer price index] inflation and a freeze in net headcount,” it said.

“The public wage negotiations currently under way will be an early and important test of the government’s capacity to deliver on its new targets.”

Nazrien Kader, the national tax leader of the advisory firm Deloitte, said Nene had clearly indicated that he would rely on the recommendations of the Davis tax committee in making any tax policy changes.

Judge Dennis Davis, who heads the committee, has said publicly that steps such as an increase in the marginal tax rate to 45% would not generate sufficient revenue, Kader said.

Referring to remarks Davis made at a Deloitte client event held earlier this year, Kader highlighted the losses to the fiscus through VAT fraud, estimated at R2-billion a month or R24-billion annually.

In the light of that, Kader said increased tax revenue could come from a greater emphasis on “supervising taxpayers and making them pay what’s due”, as well as a focus on base erosion and profit shifting.

Hiding profits

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, these are dubious tax strategies that exploit gaps and mismatches in tax rules to make profits “disappear”, or that shift profits to no- or low-tax places where the businesses have little or no economic activity.

The issue of base erosion and profit shifting is confounding tax authorities globally, as governments everywhere face declining revenues in the wake of the financial crisis.

The Davis tax committee is also studying the issue.

Speaking to the Mail & Guardian last week, Davis said it was important to combat these kinds of activities, which could “amount to quite a few billion”.

He also stressed the importance of addressing corruption, which, if it could be reduced by R20-billion, would have the same effect as increasing the VAT rate by 1%.

Roelof Botha, an economic adviser to PricewaterhouseCoopers, said that it was critical to implement policies such as the National Development Plan to boost growth, increase employment and broaden the tax base.

He said the implementation earlier this year of the government’s employment tax incentive, which had created over 200 000 jobs, was a case in point. He estimated that, if these jobs could be sustained for a year, it could generate about R2-billion in additional revenue for the fiscus.

This would be generated by the indirect taxes received through the consumption spending of these workers, who were previously unemployed. The taxes included VAT, excise duties, fuel tax and the electricity levy.

“The beauty of this is that prior to the … subsidy there was nothing,” Botha said. “This is manna from heaven.”

If, in the next 10 years, the government could create and sustain one million jobs, it could generate R10-billion in additional revenue, he said.

Expanding the economy and extending policies such as the employment tax incentive reduced the need for tax increases.

Nevertheless, an increase in VAT could be one option for the government, Botha said.

Increasing the VAT rate on semi-durable and durable goods to higher levels of between 16% and 20% would be another. And this was unlikely to be criticised by the labour unions, who view VAT hikes as detrimental to the poor, because it would target upper-income earners.