Seabelo Senatla during day 1 of the 2014 USA Sevens at Sam Boyd Stadium on January 24 2014 in Las Vegas.

Unconventional policy in the developed world can wreak havoc in the emerging markets, but there is a way to fight back, according to Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel prize-winning economist.

Speaking at an economic policy dialogue hosted by the department of trade and industry, Stiglitz said that, instead of focusing single-mindedly on inflation targeting, primarily the role of central banks, South Africa’s macroeconomic policy should also concentrate on employment, growth and financial stability.

The South African Reserve Bank has used inflation targeting for 14 years and has allowed the exchange rate to act as a shock absorber, the bank’s outgoing governor Gill Marcus has said. Last week the Reserve Bank held a conference in Pretoria – “14 years of inflation targeting in South African and the challenge of a changing mandate” – which reaffirmed the bank’s position that inflation targeting had been effective and positive.

Economic development

But Stiglitz said exchange rate policies were key in protecting the domestic economy from global spillover and for boosting economic development.

South Africa’s view on the exchange rate was to “leave it to the market”, he said. But, because of the nonmarket intervention policy of the United States Federal Reserve, it spent $3.5-trillion in buying bonds. “It’s no longer a market phenomenon, it’s political.

“Should your exchange rate be decided in Washington or in South Africa? One has to countervail others’ policies, otherwise you will be a victim of them,” Stiglitz said.

In South Africa, views on policy directions in the government can be notably divergent, with the Reserve Bank and the treasury often in one corner and trade and industry and economic development in the other. In trade and industry it’s broadly held that an extremely volatile currency and a high exchange rate impose serious constraints on manufacturing and exports in particular.

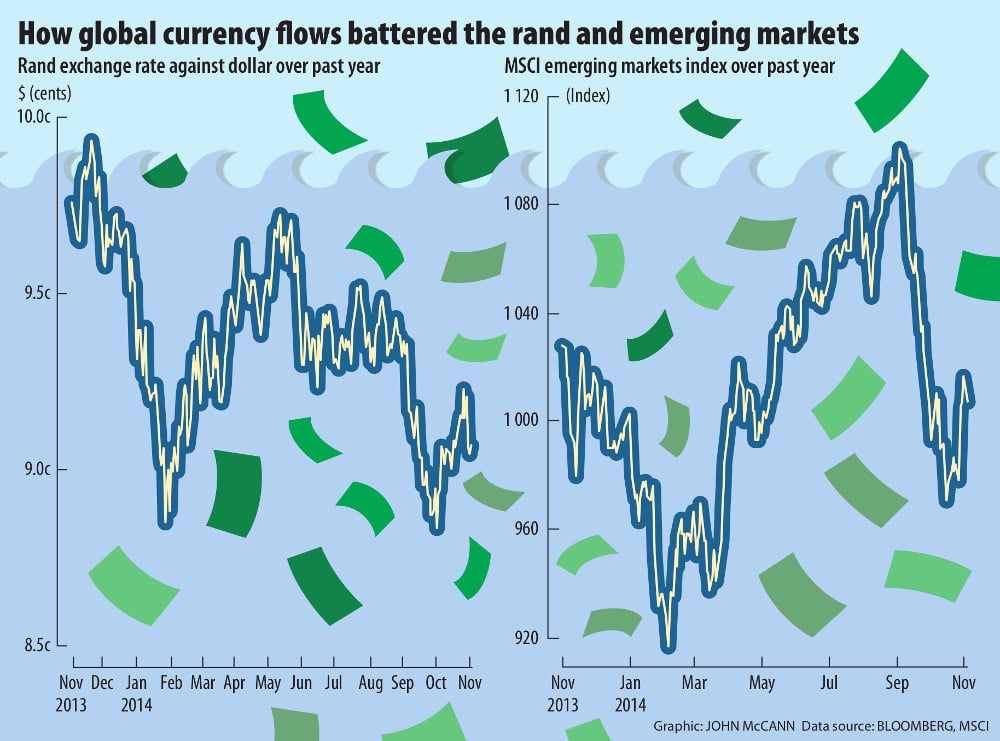

Quantitative easing (QE) in the US saw cheap money being pumped into the global economy, which flowed to emerging economies that offered higher yields. But with the programme having ended this month, interest rates are likely to rise, money will continue to leave emerging markets and, in South Africa, cause further volatility in the rand and deter investment in job-creating sectors.

But Stiglitz said there were tools at South Africa’s disposal, which ranged from taxing capital inflows or outflows – and even direct interventions such as printing domestic currency to bolster US dollar reserves.

Although most economists believed that inflation targeting by central banks could maintain price stability in a global financial crisis, Stiglitz said it “is now viewed to be a misguided perspective” and was in fact a cause of the crisis. Monetary policy should look at financial stability and “needs to focus on capital flows and the exchange rate”, he said.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), in a report titled Monetary Policy in the New Normal, agreed a greater focus on macro-stability was required.

Stiglitz said positions were changing around the world, and questions about inequality and job creation, never monitored by central banks before, had become central in the discussion about macroeconomic performance. For instance, the US Fed was not just focusing on inflation in assessing when to hike rates but also on employment, he said.

“It’s not just market forces, it’s government policy in other countries … Inflows and outflows should be targeted,” he said. “Markets are very unstable. They are irrational.”

Capital account regulations were focused on capital flows and took various forms. Chile taxed capital inflows and Malaysia had imposed a tax on capital outflows, he said. Controlling the flow of money coming in and going out reduced exchange rate volatility and increased monetary independence.

Another option, Stiglitz said, was direct intervention – buying and selling foreign exchange to bring the exchange rate down and to build up reserves. “You are selling rands and buying dollars. You can produce as many as you want and, if others want to buy it, so be it.” Reserves could then be invested in diversified assets to gain higher yields, too, he said.

Another major source of volatility was resource prices. Some countries, such as Chile and Norway, handled the volatility by creating funds to stabilise their exchange rates in the face of unstable resource prices.

“It’s going to have to be, in a broad sense, a toolkit adjusted for the circumstances you are facing,” he said.

Speaking at the Reserve Bank’s conference last week, John B Taylor, a professor of economics at Stanford University, delivered the key address and called for quite the opposite of what Stiglitz has advocated: more conventional policy.

Taylor spoke of a global deviation from rules-based monetary policy both before and after the financial crisis and, “in my view, this shift in policy has not been beneficial, but rather a factor in the deterioration of economic performance in the past decade”.

He said the adoption of inflation targeting at the turn of the 21st century was, “for the most part, beneficial”, leading to a more stable macroeconomic environment despite significant shocks from abroad.

The deviation from the rules had affected inflation targeting in emerging markets.

Economic spillovers had translated into policy spillovers, meaning “emerging market central banks have been driven to deviate from their inflation targeting”.

He said some authorities, even the IMF, were calling for a “new normal” for monetary policy. Instead, he said, they should normalise monetary policy. “For the emerging market countries like South Africa, this means sticking to the type of inflation targeting they adopted a decade or more ago,” Taylor said. For the US, there should be a return to the rules-based monetary policy that worked so well in the 1980s and 1990s.

“Research and experience show that, if such a policy framework were implemented by central banks in emerging markets and developed countries around the world, a more smoothly operating international monetary system would emerge.”

Capital controls, he said, created market distortions, potentially leading to instability as borrowers and lenders tried to circumvent them and policymakers sought even more controls to prevent the circumventions. Currency interventions could have adverse side effects, even if they stabilised exchange rates for a while. “Currency intervention leads to an accumulation of international reserves which must be invested elsewhere,” Taylor said.

Also speaking at the Reserve Bank conference, the president and chief executive of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, John Williams, said concern about financial stability was potentially dangerous, distracting policymakers’ attention from maintaining price stability.

Calling for a financial stability goal in monetary policy raised the important issue of how to take financial stability into account while preserving the nominal anchor. “If financial stability and price stability goals are in conflict, there is a risk that price stability will be subordinated to the financial stability goal, with serious long-running consequences for economic performance,” Williams said.

Manufacturing

But Stiglitz argued that, where exchange rate policies had been developed and implemented successfully, it had created more scope for the key manufacturing sector, which had positive spillover effects.

However, the sector was sensitive to exchange rate fluctuations and South Africa’s experience was deindustrialisation, with the sector making up a smaller and smaller percentage of gross domestic product.

“The consequence if you are not stable is you won’t get the kind of investment response you hope for.”

Even if the exchange rate came down, investors would be apprehensive about South Africa’s long-term record of volatility and its policy stance, which was “whatever happens to the exchange rate, we accept”.

“The fact of the matter is, if you look at the most successful developing emerging markets, they are in East Asia, and they use competitive, stable exchange rate policy for promoting the development of their manufacturing sectors.”

But exchange rate policy was not a panacea on its own and many countries had implemented exchange controls without having other necessary conditions, such as adequate infrastructure, electricity or access to credit. Others satisfied those conditions but had no exchange rate controls. So complementary policies were needed to make manufacturing in emerging economies attractive, he said.

“The object here is not perfect stability of exchange rate. “It’s not going to be able to stand up against a deluge of QE, but at least you can try and reduce the deluge a little bit.”

Kevin Lings, Stanlib’s chief economist, said: “These suggestions have been around before and will be around in time. Any time currencies come under pressure the instant reaction is to put speed bumps in the way. My sense of it is, where countries have tried that, it didn’t work.”

The rand was volatile but the real answer was not to regulate the symptom, Lings said. “We need to address structural issues systematically and over time we will see a benefit … I’m not convinced the remedy is to target exchange controls.”

Dennis Dykes, Nedbank’s chief economist, said central banks were there to ensure inflation didn’t get out of hand. But that was not to say you should never have unconventional policies, he said. “When you have extraordinary times it does call for extraordinary measures. But what is afflicting emerging markets is that they have feasted a little bit too much.”